Why a US court agrees Google Books is a 'card catalog for the digital age'

Loading...

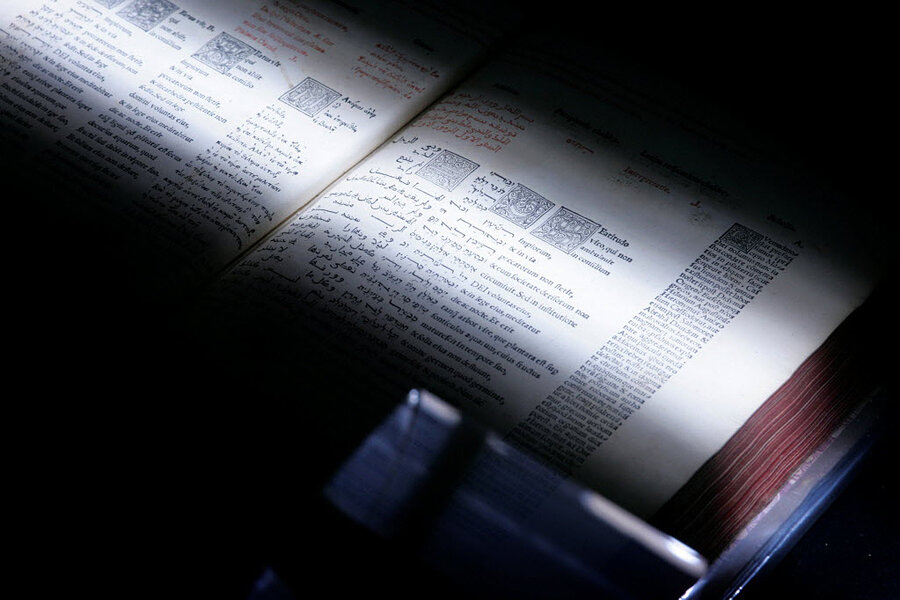

Since 2004, Google has scanned millions of books from research libraries in an effort to create a global digital library.

The effort has long troubled publishers and writers. In 2005, the American Association of Publishers sued Google, arguing that copyrights were infringed when the search giant made their books freely available online. But a series of court decisions, most recently on Friday, have mostly backed Google, finding that the company’s book-scanning project is protected as "fair use."

The Author’s Guild, which launched the current case, has stressed the book-scanning project's economic impact on writers. They called the court’s decision "damaging" and said they plan to appeal.

"Most full-time authors live on the perilous edge of being able to sustain themselves through writing as a profession ... so even relatively small losses in income can make it unsustainable to continue writing for a living," said Mary Rasenberger, the organization executive director, in a statement.

"Snippets" as fair use

On Friday, the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a lower court's 2013 ruling that Google’s search – which allows a user to search for individual words and then view a "snippet" of the resulting books – is a "highly transformative" use of authors’ books.

Because only limited pieces of the books are available in snippet view, the court ruled, it doesn’t threaten the authors’ ability to sell their books. Google’s status as a for-profit company also doesn’t change the fact that its book-scanning project is fair use, the three-justice panel said.

"Many of the most universally accepted forms of fair use, such as news reporting and commentary, quotation in historical or analytic books, reviews of books, and performances, as well as parody, are all normally done commercially for profit," wrote Circuit Court Judge Pierre N. Leval, who introduced the concept of "transformative" fair use in a 1990 law review article.

Google welcomed the ruling, having long maintained that its goal is to improve access to hard-to-find and out-of-print books. It calls Google Books "a card catalog for the digital age."

Google spokesman Aaron Stein said, "Today's decision underlines what people who use the service tell us: Google Books gives them a useful and easy way to find books they want to read and buy, while at the same time benefiting copyright holders," he said.

Google did not respond to a request for comment from The Christian Science Monitor.

The decisions in Google’s favor have been particularly championed by librarians, who say the project can provide access to books for scholarly research and enable projects such as "data mining" – pulling text en masse from thousands of books in order to analyze patterns in language use.

Libraries say it will also improve access to books for people with disabilities, which was the focus of a 2014 Second Circuit decision that ruled that "HathiTrust" – a collaboration among research libraries working with Google Books to make a variety of materials available online – also did not violate the authors’ copyright.

After Friday's ruling, Ann Campion Riley, the president of the Association of College and Research Libraries, said:

I join my colleagues in applauding this ruling as it strongly supports fair use principles, allowing scholars and others to discover a wealth of resources. This is a tremendous opportunity for our communities, in particular for students and others with visual disabilities, as Google Book search makes millions of books searchable.

Transformative fair use

Google Books’ declaration as fair use has roots in an entirely different industry – a 1994 Supreme Court case involving the controversial Florida rap group 2 Live Crew, perhaps best known for their 1992 album, “As Nasty as They Wanna Be.”

In that case, a song from that album’s “clean” version called “Pretty Woman” sampled a 1965 rock ballad by singer Roy Orbison called “Oh, Pretty Woman,” leading to a suit from Mr. Orbison’s record company. But 2 Live Crew argued their song was intended as a parody, including changed lyrics.

The high court agreed, citing the work of Judge Leval, then a federal district court judge in New York, on "transformative" fair use.

"Suffice it to say now that parody has an obvious claim to transformative value, as Acuff Rose [Orbison’s record company] itself does not deny," wrote then-Supreme Court Justice David Souter. "Like less ostensibly humorous forms of criticism, it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one."

Some legal scholars and commentators have speculated that in his decision in favor of Google Books, Judge Leval was revisiting his vision for a more expansive definition of fair use originally laid out 25 years ago.

Since the origins of copyright law in England in the 18th century, Leval wrote, "Courts have recognized that, in certain circumstances, giving authors absolute control over all copying from their works would tend in some circumstances to limit, rather than expand, public knowledge."