North Korea clamps down on already spare Internet access

Loading...

| Tokyo

North Korea, already one of the least-wired places in the world, appears to be cracking down on the use of the Internet by even the small number of foreigners who can access it with relative freedom by blacklisting and blocking social media accounts or websites deemed to carry harmful content.

The move won't be noticed by most in the North since hardly anyone has access to the Internet. But it could signal increasing concern in Pyongyang over the flow of real-time photos, tweets and status updates getting out to the world and an attempt to further limit what the few North Koreans able to view the Internet can see.

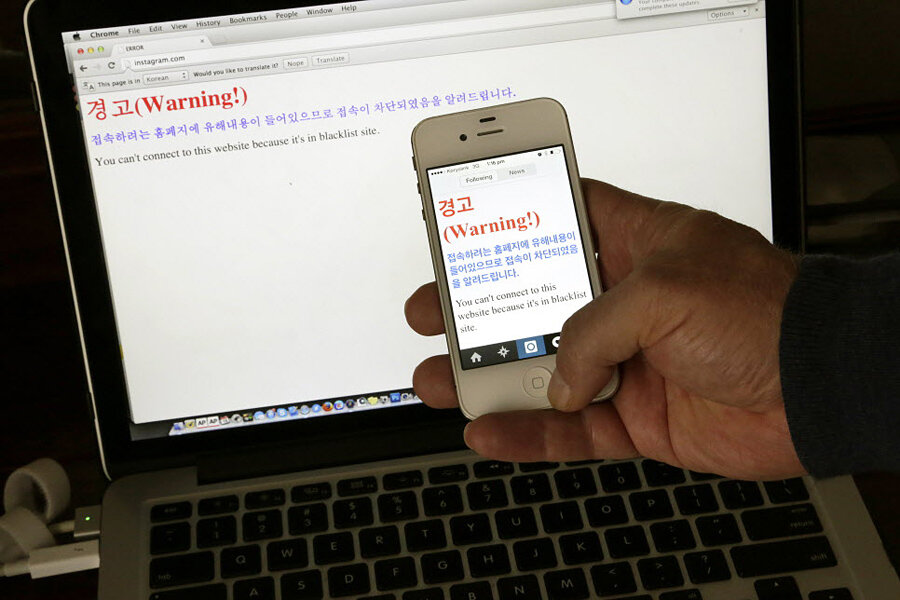

Warnings, in Korean and English, are now appearing on a wide array of sites, including social media such as Instagram, Tumblr and Flickr and websites like the South Korean news agency Yonhap, along with specific articles about the country. The warnings say the sites have been blacklisted for harmful content and cannot be accessed.

There has been no announcement of a policy change by the North Korean government or the North's mobile service carrier, Koryolink, a joint venture with Egypt's Orascom Telecom and Media Technology. With no official confirmation, it was impossible to rule out the possibility the warnings resulted from a hack of some sort.

The explicit blacklisting of sites would be a break with past practice in North Korea, when officials most likely monitored the Internet activity of foreign users but did so quietly. The 3G data connection on mobile phones itself has not been disrupted and many sites, including Facebook and Twitter, continued to function normally.

But signs of concern that local eyes may be trying to peek into the crack opened for foreigners to use the Internet have been growing.

From late last year, Koryolink began blocking the function that allows smart phones to be turned into wifi hotspots that can share their Internet connection with other nearby devices. Officials last year also tightened restrictions on wifi use at embassies, probably to keep local residents from illegally "piggybacking" off of wifi signals near their compounds.

If not the result of a hack, the scattershot nature of the blacklist warnings and the relative ease with which they can be circumvented would suggest a more tentative and possibly experimental effort at controlling Internet use than the sophisticated Great Firewall that makes it impossible for most Chinese to access Facebook or even the widespread government censorship of Internet sites in South Korea.

"This effort seems a bit random," said James Lewis, an expert in computer security who is a director and senior fellow at the Washington D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies. "Why send a warning about some sites, block some, but not block others? Either the DPRK is developing a more comprehensive policy but changed their mind, or they've been hacked."

Lewis added, however, that countries have the right to control their national networks.

"In practice, authoritarian regimes or religious regimes control more, democratic regimes control less," he said. "It's expensive, so there are often ways to circumvent controls, but most users are too lazy to do this."

Shutting down a particular user or group of users on a social media site isn't difficult. It can be done either by blocking access to IP addresses or by malicious codes. Instagram itself can and does shut down accounts reported for spam or inappropriate content. Filters to block out specific sites, like the ones used by parents to keep children from viewing adult content, aren't unusual either.

For most North Koreans, official interference with online activity is anything but subtle.

Instead of the World Wide Web, North Korea has its own "intranet," which looks a lot like the Internet but is sealed off from the global web and allows users to access only a tiny number of government-sanctioned websites. The few North Koreans who are granted Internet access — including some government and military officials, IT technicians and computer science students — get it only in public settings under close supervision.

Cell phones are now a common sight in North Korea. There are more than 2 million in use. But while many have access to the domestic intranet and can be used for email and playing games, they cannot be used for international calls and, of course, do not have access to the Internet.

That's why the North's decision in 2013 to allow Koryolink to begin providing the 3G data service for mobile devices, while restricted to foreigners willing to pay a fairly hefty price, was seen as a litmus test of how far North Korea might be willing to go with online freedoms.

While regular users are very few in number, photos from North Korea on Instagram, in particular, have since provided a unique and largely unfiltered window on daily life in North Korea, albeit one limited by the normal restrictions on what foreigners in the North are allowed to see in the first place.

But they have also posed a quandary for North Korean officials who are highly concerned about the flow of information and images in and out of the country. Just days before the blacklist warnings were first seen in Pyongyang by The AP, photos of a fire that broke out on June 11 at a major hotel in Pyongyang were widely posted and viewed on the Internet, though the North's official media did not cover the incident or release any photographs.