'Regin' stealth malware has been spying on governments for years

Loading...

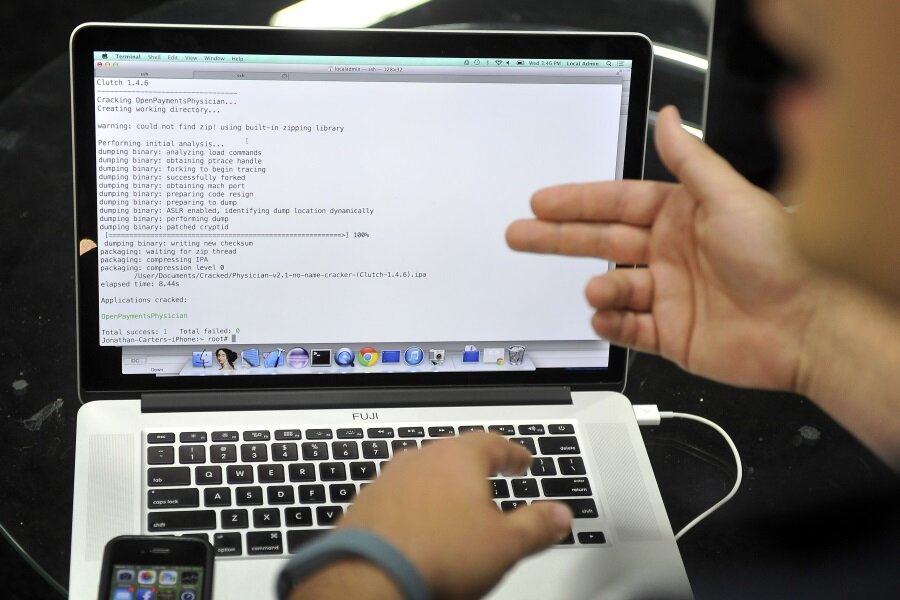

A new piece of computer malware called “Regin” has been uncovered by security researchers at Symantec, who say the software has been active since 2008, spying on governments and individuals in 10 countries, including Russia and Saudi Arabia. Regin allows for mass surveillance, and is so sophisticated that researchers say it probably took months or years to develop.

Regin is apparently designed to gain access to the phone calls of governments, small businesses, financial and research institutions, and specific individuals. It is highly targeted – fewer than 100 infections have been discovered worldwide in the last six years – and isn’t designed to steal sensitive information or to destroy important systems. As far as researchers can tell, Regin is meant to run in the shadows, watching its targets.

Symantec calls the malware “a highly complex threat which has been used in systematic data collection or intelligence gathering campaigns.”

Most of Regin’s discovered targets live in Russia (28 percent), Saudi Arabia (24 percent), or Ireland (9 percent). Symantec has also found infected systems in Mexico, Austria, Belgium, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. No one living in the US, Canada, or the UK has been infected, which leads researchers to believe that Regin wasn’t created by the “usual suspects,” China or Russia, Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at antivirus company F-Secure, told The Guardian. Regin is so complex that it was probably created by a country, rather than an individual or hacker group, says Mr. Hyppönen. And if it didn’t come from China or Russia, he says, that means it was probably written by the US, Israel, or the UK.

Regin uses five stages to take control of computers and other telecommunications devices, installing itself as a Trojan horse – meaning that it hides inside another apparently innocuous piece of software – then loading subsequent stages with custom features such as a Web traffic monitor and a data sniffer that allows it to hook in to cellphone networks. In that respect, it’s similar to the Stuxnet worm that infected nuclear control systems in Iran in 2010, and the Duqu malware, discovered in 2011, that gathered information about industrial systems.

Besides being careful not to install software from sources you don’t recognize, there’s probably nothing you need to do to protect your computer against Regin specifically. The malware is aimed at enabling large-scale surveillance, not stealing personal credit card information or other data. The handful of individuals who have been reported to have been infected work in the fields of cryptography or mathematical analysis.

Because Regin is such a complicated piece of software, Symantec says the malware may have additional functions that haven’t been discovered yet. Even when an infection has been recognized, it adds, it’s difficult to know exactly what Regin is doing since each stage helps to hide the others from view. For now, individuals living outside of the affected countries probably don’t need to worry – but governments may need to take extra steps to ensure their computer and phone systems are secure.