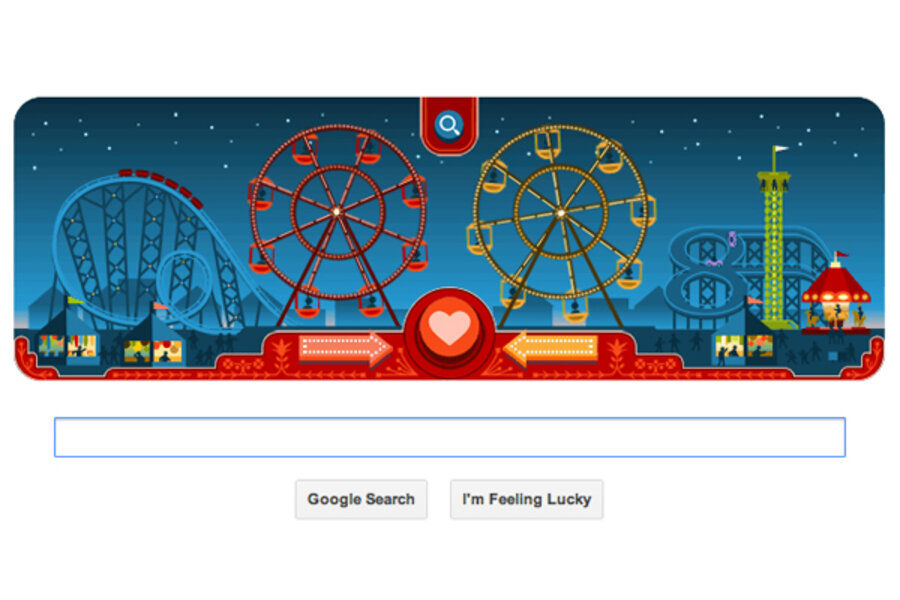

George Ferris's Valentine's Day gift to science teachers

Loading...

George Ferris, whom Google praises on its home page Thursday, did more than just invent a beloved theme park ride. His eponymous wheel serves as a perfect opportunity for physics teachers to engage in two of their favorite activities: 1) revealing the simple mathematical equations that govern the motions of everything around us, and 2) coming up with horrifying thought experiments.

Moving its occupants in a circle at a constant rate, the Ferris wheel offers a straightforward lesson in centripetal force, the force that pulls a body moving in a curved path toward the center of the curvature of that path. We often experience centripetal forces as "centrifugal" forces, that is, we feel pushed away from the center. This feeling is the effect of inertia. Like everything else with mass, you tend to travel in a straight line; when you are pulled in a circular motion, say, by a gondola bolted to a giant wheel, from your perspective you will feel as though you are being tugged outward.

Thanks to gravity, this feeling is most acute at the highest and lowest points of the wheel. The centripetal forces are always pulling the gondola toward the center, sometimes working in the exact same direction as gravity and sometimes working in the opposite direction. At the bottom, centripetal forces accelerate the seat upward into your backside, and you weigh more; at the top, the seat is pulled straight down, and you weigh less.

In 1659, the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens came up with the formula for centripetal acceleration:

ac = v2 / r

The "v" stands for velocity. The "r" stands for the radius of the circle.

This equation gives you everything you need to terrorize your imaginary amusement park visitors with one simple question: How fast does a gondola need to be moving so that its passengers briefly experience weightlessness as they crest the top of the wheel?

For that to happen, the centripetal acceleration needs to equal that of gravity, or g, as physicists like to call it, which at sea level is about 9.8 meters per second per second.

So, based on Huygens formula, we present you with the formula for Ferris wheel weightlessness. It works on a wheel of any size, on any planet:

vweightlessness = √(g • r).

George Ferris's original wheel, constructed for the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago, stood at about 80 meters, so we'll assume that the radius was 40 meters, giving the wheel a circumference of about 251 meters. In reality, the wheel took 10 minutes to complete a revolution, which meant that each gondola traveled at a stately 0.41 meters per second, or just under one mile per hour. On this wheel, a person who normally weighs 150 lbs would be about two and a half ounces lighter at the very top, and correspondingly heavier at the very bottom.

But in our scenario, the wheel's controls have been commandeered by a madman intent on finding suitable candidates for his steampunk space program. How fast would you have to spin the wheel to lift our unsuspecting Gilded Age passengers out of their seats? All we need to do is multiply the acceleration of gravity (9.8 m/s2 ) by the wheel's radius (40 m) and then take the square root of this product. The answer: about 20 meters per second, or 45 miles per hour. That works out to about five revolutions per minute. Of course, at the bottom of the spinning wheel, our poor 150-lb. passenger now weighs 300 lbs.

Bigger wheels have to spin faster for weightlessness to occur. The world's largest Ferris wheel, the Singapore Flyer, stands at 165 meters. To induce weightlessness, you would have to set the wheel to spin at 28 meters per second, or about 63 miles per hour. But for a wheel whose diameter is only 15 meters, you'd need spin at just 20 miles per hour to experience weightlessness.

Of course, in real life, a Ferris wheels offers a pleasant view and perhaps a quiet moment with your Valentine, not a harrowing lesson in Newtonian mechanics. That's why we have roller coasters, which are more complex but are governed by the same underlying rules. But for a straightforward lesson in the relationships of force, mass, and circular motion, you'd be hard pressed – perhaps literally – to beat George Ferris's elegant wheel.