Is that cracked mud on Mars? Curiosity closes in to investigate.

Loading...

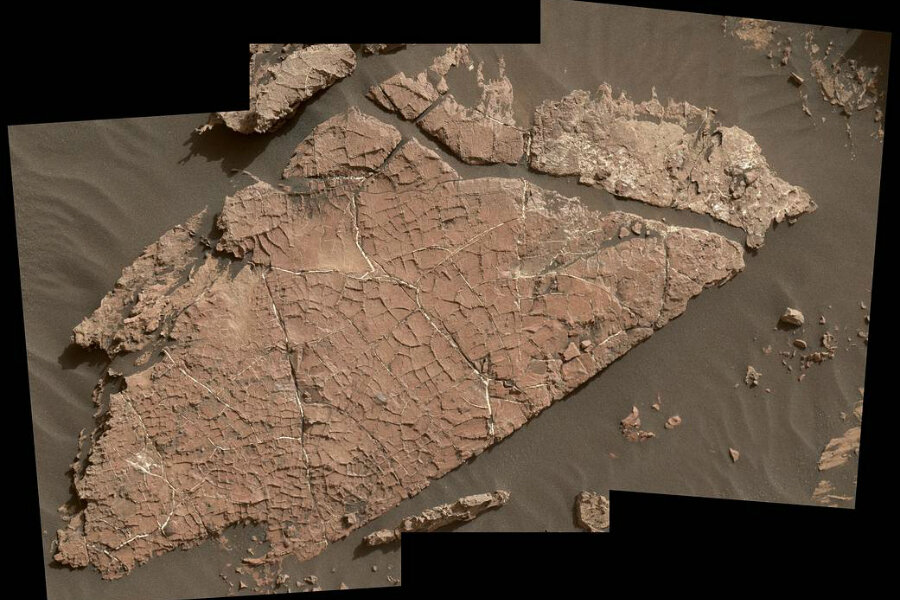

Scientists studying the surface of Mars believe they have found evidence of drying mud cracks that, if confirmed, would be a first for the Curiosity rover mission.

Curiosity, which has been crawling across the windswept Martian landscape for more than four years, previously found evidence of ancient lakes on the Red Planet. The latest discovery, announced Tuesday by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), could serve as evidence that Mars used to experience wetter conditions followed by drying periods – perhaps shedding more light on how habitable the planet's conditions might have been, and how they became less and less friendly to life.

"The ancient lakes varied in depth and extent over time, and sometimes disappeared," Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "We're seeing more evidence of dry intervals between what had been mostly a record of long-lived lakes."

The researchers said they believe the layer of cracked terrain formed more than 3 billion years ago. Sediment then buried the layer until erosion stripped it away, once again revealing the cracked pattern.

"It looks like what you'd see beside the road where muddy ground has dried and cracked," Nathan Stein, a Curiosity science team member and graduate student at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said in the statement.

"Even from a distance, we could see a pattern of four- and five-sided polygons that don't look like fractures we've seen previously with Curiosity," Mr. Stein said.

The researchers are continuing to review the data collected at the site of the suspected mud cracks, but the rover has left that area to head further uphill, where scientists hope it can drill more rocks. That could prove difficult since the part of the rover's drill that moves it up and down began malfunctioning occasionally last month.

After landing in 2012 near a site dubbed Mount Sharp, the Curiosity rover reached the mountain's base in 2014. Now more than four years in, even as the rover's instruments show signs of wear, discoveries keep coming. Just last week, researchers spotted a dark rock they suspect is another meteorite, the mission's third.

"While not yet confirmed, the turkey-shaped object has a gray, metallic luster and a lightly-dimpled texture that hints of regmaglypts," Bob King wrote for Universe Today. "Regmaglypts, indentations that resemble thumbprints in Play-Doh, are commonly seen in meteorites and caused by softer materials stripped from the rock’s surface during the brief but intense heat and pressure of its plunge through the atmosphere."

New Scientist's Leah Crane noted that Curiosity's Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) instrument would be used to verify the researchers' suspicions.

"If the ChemCam results show that it is mostly made of iron, that would confirm that this is a meteorite formed from the core of an asteroid," Ms. Crane wrote. "That would make it one of several discovered by rovers on Mars – five were found by the Opportunity rover, and the Spirit rover took pictures of two potential meteorites."

Horton Newsom, a researcher from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said a similar object, known as Egg Rock, discovered last November, could carry within its core information that differs from asteroids currently being studied.

"Iron meteorites provide records of many different asteroids that broke up, with fragments of their cores ending up on Earth and on Mars," Dr. Newsom, a member of the ChemCam team, said in a statement at the time. "Mars may have sampled a different population of asteroids than Earth has."

Iron meteorites are rare on Earth, where about 95 percent are stony and only 4.4 percent are irons and 1 percent are stony-irons, Universe Today's Mr. King wrote.

"If this were Earth," he added, "the new meteorite’s smooth, shiny texture would indicate a relatively recent fall, but who's to say how long it’s been sitting on Mars. The planet’s not without erosion from wind and temperature changes, but it lacks the oxygen and water that would really eat into an iron-nickel specimen like this one."