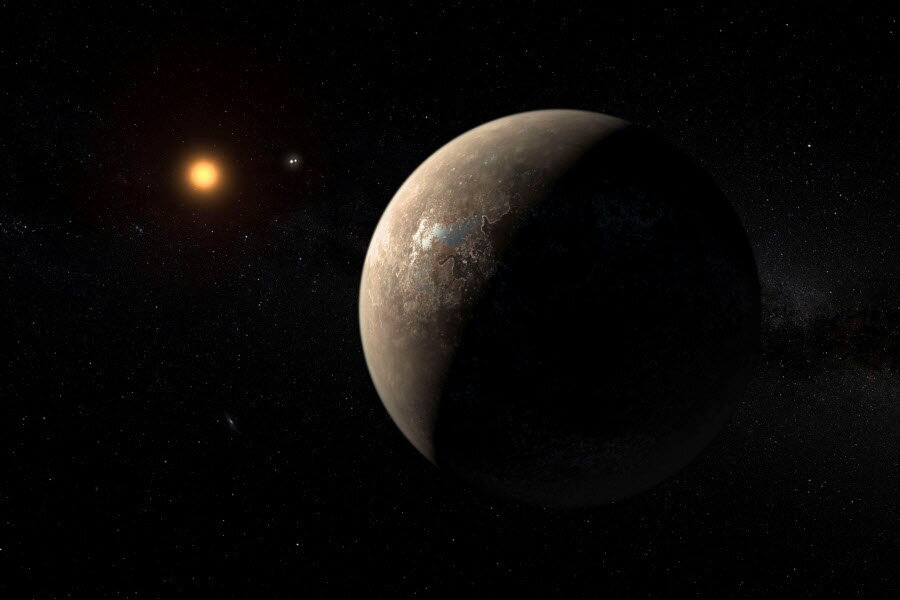

Proxima b briefing: How close is it, and when can we get there?

Loading...

Astronomers announced this week that Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to our own solar system, has an orbiting planet – Proxima b – that is only 30 percent larger than Earth and could be warm enough to have liquid water. We've rounded up some frequently asked questions to catch you up to speed.

The news keeps saying that Proxima Centauri is 'in our backyard.' Is it really?

Other than our own sun, which is a medium-sized yellow star, Proxima Centauri is the closest star to Earth in the universe. (That's how it got the name – "proxima" is the Latin word for "close".) Yes, it's our stellar next-door-neighbor, but considering the enormity of outer space, that's still pretty far away.

So how far away is Proxima b?

About 4.24 light-years, which is roughly 25 trillion miles. In other words, it's about 270,000 times farther away than the sun.

What kind of a mission could we send?

The only proposal likely to get a spacecraft there within the next few decades would be a "wafersat" or "nanobot," essentially a postage-stamp-sized microchip carried by a light-sail about 10 feet across, propelled by Earth-based lasers that push it to about one-fifth the speed of light (roughly 100 million miles per hour).

As exciting as it would be to send humans, says says SETI astronomer Laurance Doyle, "We don't have spacecraft that go that fast yet." The fastest crewed mission ever flown by NASA, carrying the Apollo 10 crew back to Earth, only got up to about 25,000 miles an hour, he notes.

How soon would it get there?

If a wafersat successfully accelerated to one-fifth of light speed, it would get to Proxima b in about 20 years. It could then take as many photos or measurements as its "nanocraft" would allow, then beam back the results to Earth scientists. The data would come back at the speed of light, so we could start getting results a little more than 4 years after the spacecraft arrived. In other words, if engineers and scientists can design, build, and launch this fleet of wafersats in 10 years, we could get results by 2050.

But 10 years till launch is very ambitious, since researchers still need to prove that the underlying technology works as well in the real world as it does in theory.

How much could a nanocraft hold?

Miniaturization keeps improving – just look at your smartphone, which has more processing power than the Apollo mission computers – so it's hard to predict how much scientists could load onto a few grams of a spacecraft in a decade. Fortunately, even just a few tiny instruments could provide a huge amount of information.

"If you're going to go all the way there, you want pictures, and you want to know if it's inhabited or not. Other things are details," says Doyle, in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. "Those are the main goals: pictures and spectrographic analysis of the planet."

"A spacecraft equipped with a camera and various filters could take color images of the planet and infer whether it is green (harboring life as we know it), blue (with water oceans on its surface) or just brown (dry rock)," wrote Abraham Loeb, a Harvard University astrophysicist and a Starshot mission advisor, in an email to reporters.

Is anyone working on this?

In April, Stephen Hawking and Russian billionaire Yuri Milner proposed sending hundreds of nanobots toward Alpha Centuri. They listed 20 likely challenges to the mission, and offered $100 million in research funding to investigate them all. A Harvard team led by Professor Loeb has just published their results from tackling the first question: Could interstellar dust pulverize a wafersat?

Wait, what's the risk from interstellar dust?

If a grain of dust only 15 microns across – that's a third the width of a strand of hair – runs into one of these tiny satellites, it could completely destroy the nanocraft, Loeb and his colleagues reported.

Fortunately, that's enormous, as far as interstellar material is concerned. "There is no measurement of dust between us and Proxima Cen that amounts to anything," says Maggie Turnbull, an astrobiologist with SETI, in a phone interview with the Monitor. "That doesn't mean there's none, but the densities are very low," she says.

Loeb's team calculated that the odds of hitting something that big were about one in a trillion, trillion, trillion, trillion.

On the other hand, there are plenty of smaller particles in the interstellar medium, and for a ship traveling a good fraction of the speed of light, even a single atom can cause some damage. Loeb and his colleagues calculated that collision with a submicroscopic particle would vaporize a few atoms from the nanocraft's surface, essentially producing a tiny crater. Over the 25-trillion-mile journey, the craft would hit enough of these to have pockmarked its entire surface by arrival, making it unlikely it would be able to do any science.

The researchers recommended either reducing the craft's cross-section – maybe by folding up the light-sail – or coating it with a stronger material than silica, like graphite. Of course, graphite is also heavier than silica, and every gram makes it harder to get the craft up to speed.

Why are scientists already so excited about this?

"Primarily because it's our nearest neighbor, and it shows how little we know about the stars in the sky," says Dr. Turnbull.

"It shows how we have to look really deeply at each individual star system and try to get to know it, because they're all so different from each other," she continued. Most astronomy missions and programs focus on the broad sweep of the sky, she said, like trying to determine how many exoplanets there are in total, but this discovery encourages a "deep dive" into this particular star system.

"The whole field has basically dropped whatever it was doing before, and it's just really focused on this one star right now, and I love that," says Trumbull.

She adds, "The more you know about something, the more questions it raises."