Water may have had a much longer history on Mars than we thought

Loading...

By using mathematical models to tilt Mars's surface 20 degrees, an international team of scientists have upended current predictions about the history of water on the Red Planet.

Their findings, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, suggest that the climate conditions of young Mars allowed water to flow there for a longer period of time than scientists previously thought, which would have allowed more time for life to form on the planet.

“Generally, the longer you have large volumes of stable water on the planet, the more likely it is for life to arrive,” Isamu Matsuyama, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona who was part of the research team, told The Christian Science Monitor in an interview. “Although, that’s all speculative,” he cautioned.

The researchers didn’t set out to find life. They simply wanted to know what the topography of young Mars looked like in the first billion or so years of the planet’s evolution.

They concluded that about 3.2 billion years ago, centripetal forces on the rotating planet shifted the whole outer surface of Mars about 20 degrees, to move the bulging mass of a growing volcanic region, called Tharsis, toward the equator.

"It’s as if Paris shifted to the north pole or if we turned the flesh of an apricot around its stone!" explained Sylvain Bouley, a geomorphologist at Université Paris-Sud and lead scientist on the paper. This event is known as a "true polar wander."

Tharsis is the largest volcanic region on Mars, measuring nearly 2,500 miles across and 6 miles high. Its 3 massive and 9 smaller volcanoes are up to 100 times bigger than any on Earth.

This volcanic region is thought to have formed very early in Mars’s history, more than 3.7 billion years ago, during the planet's Noachian era, the earliest and wettest of Mars's geological periods.

The conventional scientific wisdom is that systems of river valleys were carved after Tharsis had mostly formed during this period.

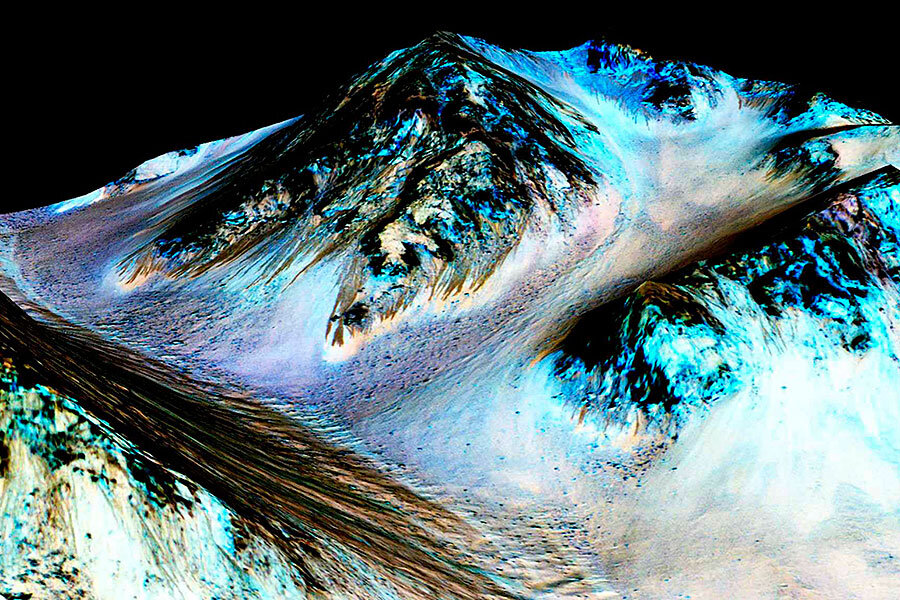

As the region grew taller because of the buildup of lava from the continual volcanic activity, the thinking goes, the incline caused rivers to flow away from the Tharsis bulge. Scientists believe there were rivers there because the valleys – parched remnants of wetter times – look like river valleys on Earth, carved into the terrain.

But the research team mathematically removed Tharsis from the planet in its models of young Mars, thus tilting the planet back to where it would have been billions of years ago.

They found that the original topography of Mars would have allowed the rivers to flow in the same patterns, regardless of Tharsis, “from the cratered highlands of the southern hemisphere to the low plains of the northern hemisphere,” according to an announcement from the research team, which includes scientists from France, Senegal, and the United States.

That suggests that the valleys could have formed earlier, either before the formation of Tharsis or contemporaneous with it. The river valleys could have been replenished by melting polar ice caps, heated by a climate that was warmed by the gases that spewed from the volcanoes and trapped heat in the atmosphere.

The research team also says that the volcanoes erupted enormous volumes of lava for at least half a billion years longer than currently accepted.

If true, this could change the age of Mars's rivers by hundreds of millions of years, giving life more time to form there.

“This study upsets our picture of the surface of Mars as it must have been 4 billion years ago, and modifies the timing of events profoundly,” write the scientists in their announcement.

“From now on, when we study the earliest days of Mars, we must learn to think with this new geography,” they write.

Their findings support the recent “paradoxical” findings of NASA’s Curiosity rover, which has found by studying the Gale Crater on Mars that the basin was filled with water for hundreds or even thousands of years, but at a time in Mars’ evolution when scientists thought that the planet was drying out.

“From a practical point of view, if water was around later, it better helps explain everything we’re finding with Curiosity,” says Ashwin R. Vasavada, a NASA scientist on the Curiosity project who was not involved in the Tharsis paper, during an interview with the Monitor.

“This extended Tharsis volcanism may be the key to explaining why the climate remained conducive to liquid,” he says.