Did prehistoric climate change help make us human?

Loading...

For years, Rick Potts has excavated ancient stone tools in southern Kenya, at a site called Olorgesailie, seeking to piece together a picture of what life was like for early humans who lived there. But he and his colleagues were puzzled by what seemed to be a technological leap forward.

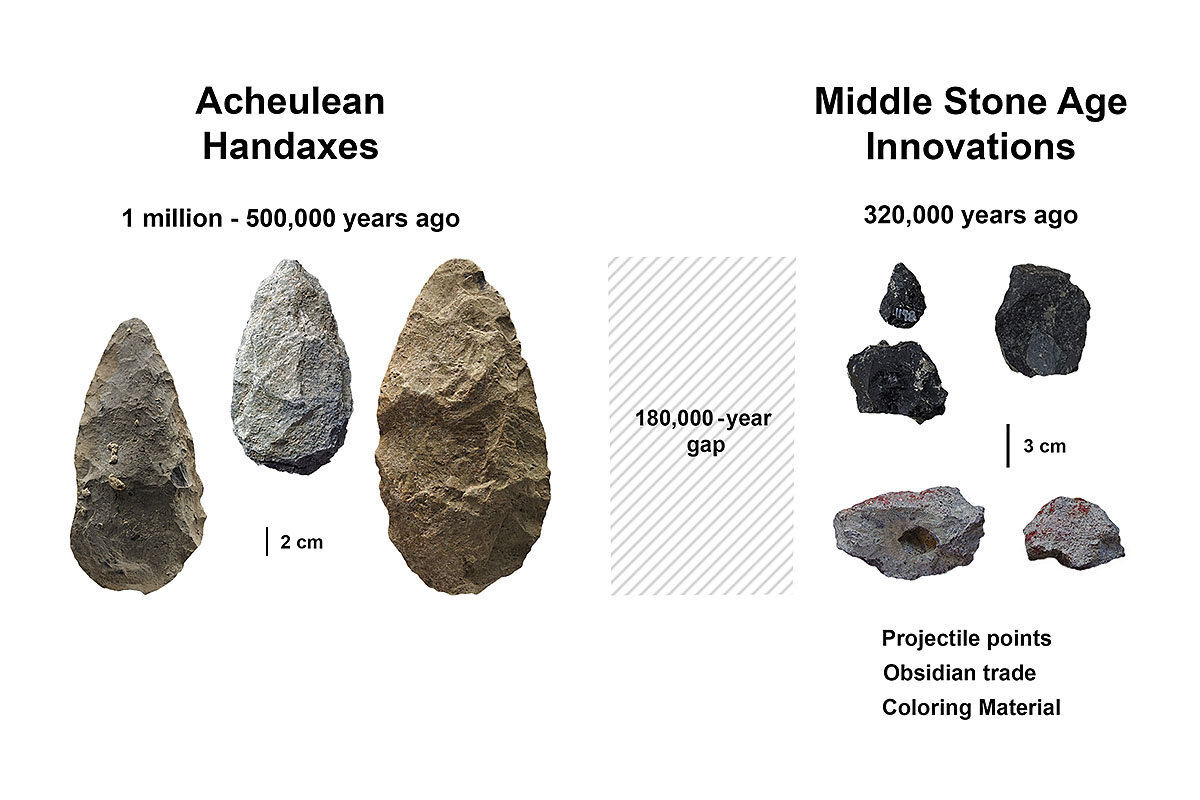

Dr. Potts, the director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Human Origins Program, said that the site yielded hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of stone hand axes, suggesting its residents were prolific toolmakers. But those tools seemed to disappear 500,000 years ago, and the next 180,000 years of the archeological record were missing, swept away by erosion.

The next tools show up in sediments that are some 320,000 years old, and those tools seem to indicate a cultural leap, one that could add to the story of the origins of our species.

Why We Wrote This

News of climate change sparks concern, but it also brings out humanity’s most prominent trait: the ability to innovate. One recent study suggests that this was as true in our distant past as it is today.

But what prompted this leap? With no clear transition in the archaeological record at Olorgesailie the research team was left puzzled.

Dr. Potts and his colleagues found a spot about 15 miles away in the nearby Koora basin where they could extract a core of sediments from deep in the ground to assemble a timeline of the environmental conditions for the last million years.

“And it turns out that the missing time, that 180,000 year gap, is beautifully recorded in the core – thank goodness,” says Dr. Potts.

As the core revealed, a lot happened in those 180,000 years. Beginning about 400,000 years ago tectonic activity fractured East Africa’s landscape into small basins, the landscape alternated between arid grasslands and fertile woodlands. Large herbivores died out, replaced by smaller mammals with diverse diets.

And human behavior changed, too, says Dr. Potts, connecting the technological transition to the ecological context. ”We’re really looking at the foundation of how humans adjust to environmental disruption,” he says. And, according to a paper published by Dr. Potts and the research team on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, that rapid climate change might explain what drove those early humans to innovate.

Emerging humanity

Piecing together early human history is often like assembling multiple puzzles without all the pieces in the boxes. Researchers do their best to imagine the whole picture from some fragmentary fossils, artifacts, and what environmental data they can gather from the geologic record. But big questions remain.

One of these is how the world went from having several human species – members of the genus Homo – to just one, Homo sapiens. Why did our species survive when others did not?

While this new study does not point directly to the origin of our species (the oldest fossil found with H. sapiens features has been dated to around 315,000 years ago), it might still provide some pieces of the puzzle.

The artifacts unearthed at Olorgesailie from around 320,000 years ago are markedly different from the earlier artifacts in a way thought to be emblematic of the technology and culture of more modern humans.

First, while the ancient stone hand axes were large and fairly uniform in shape, likely used for multiple purposes, the newer tools were smaller and more diverse. Some appeared to be projectile points. Others, blades or flake tools.

What’s more, while the older tools were made from stones that could be found nearby, some of the newer ones were made of rocks like obsidian that had to have been imported. This, the researchers posit, suggests that the humans at Olorgesailie had begun to engage in long-distance trade with other groups.

And that’s not all. There’s also evidence that the Olorgesailie residents were using pigments, which anthropologists often take as a sign of symbolic communication.

“All of that contributes to this strong impression that they are using their landscape and the resources available in it in a much more sensitive way, they’re not doing the same thing all the time,” says Julia Lee-Thorp, emeritus professor of archaeological science at the University of Oxford. “It is a feature of humans that they were using material culture to exploit the resources that were available to them.”

Lessons for the future?

But does that mean this new paper is providing pieces that fit in the puzzle of the origin of our species, H. sapiens?

Perhaps. This turbulent, rapidly changing environment was likely “the crucible from which modern humans sprang,” says Professor Lee-Thorp, and it’s certainly a driver of human evolution.

Still, cautions Pamela Willoughby, chair of the department of anthropology at the University of Alberta, there are instances in the archaeological record where technology seems to leap forward for a bit of time but then return to older styles of tools, or doesn’t change across the landscape as it does in a single site.

“I think this is a fascinating case study,” she says. “It involves lines of evidence from just about every source that you can get” with a massive, interdisciplinary research team behind it. But it remains to be seen whether these patterns appear across Africa at that time, Dr. Willoughby says.

However, most researchers agree that there’s something about the ability to be flexible in the face of change that seems to set H. sapiens apart.

“This is kind of defining in ancient times how our species adapts, how it adjusts to times of environmental disruption, or the shift from more stable, reliable times, to times of uncertainty,” Dr. Potts says.

And, as we enter another period of global climate instability, these findings may inform humanity’s response.

“The question is, does this work in the face of nation-states?” Dr. Potts asks. “Does it work in the face of big institutions? Does it work in the face of all of those things that have developed in civilization during a period of thousands of years of relative stability in our ecosystems and environment, which are now becoming disrupted?”

With so many more humans living across the entire world in a truly globalized society, Professor Lee-Thorp says, “It’s a very different situation” today than it was in ancient times. “But one would have to hope that human ingenuity would be able to get its head around it, and do something about it. Otherwise we’re in deep doo-doo.”