Racing to space, together

Loading...

Gone are the days of the bilateral space race between the United States and the former Soviet Union. Today’s global landscape of spaceflight is much more diverse – and more collaborative.

The original space race was tinged by fears around the coupling of militaristic and space-faring capabilities, and by two superpowers’ dance for dominance. But now space exploration is predominantly driven by the shared human desire to render the impossible possible.

Today’s space endeavors strike both competitive and collaborative tones. As nations pursue an ever-broader variety of space exploration goals and rely more heavily on collaboration with other countries, competition has become less fierce. A competitive drive still serves to inspire and motivate governments, individual visionaries, and the general public to reach higher, space historians say, but the tone is markedly different.

“There is no space race like the original space race,” says Michael Neufeld, a senior curator in the Space History Department at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington. Still, Dr. Neufeld says, “There are kind of little races.”

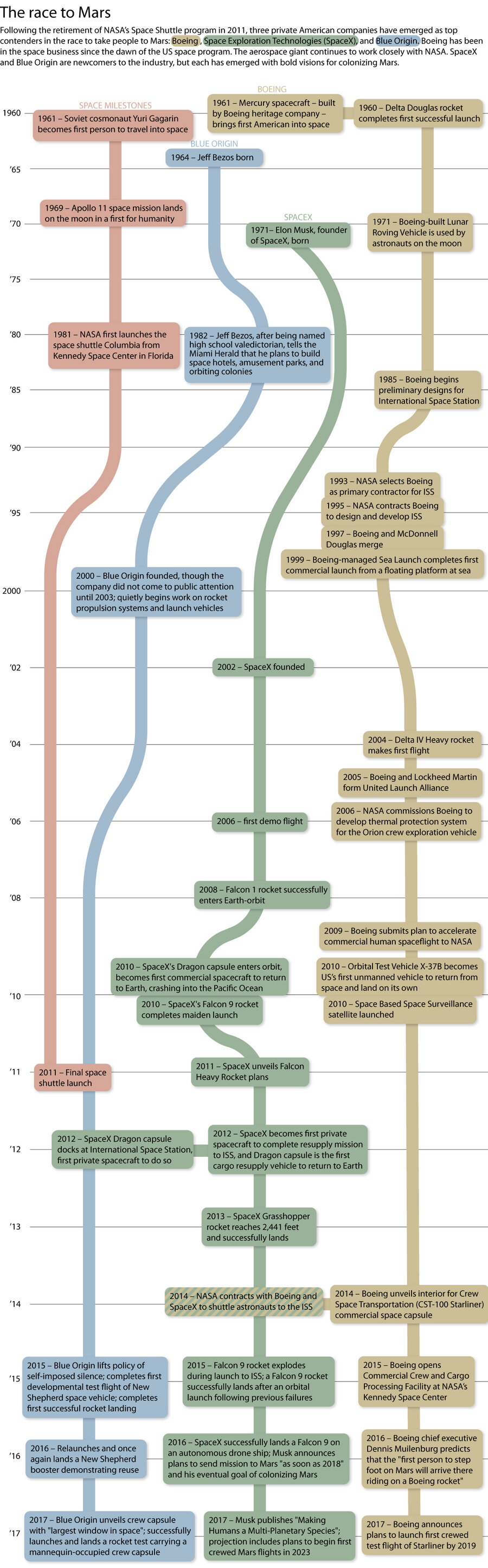

The competitive spirit is most visible today in the private sector, where newcomers like SpaceX and Blue Origin are competing with spaceflight veteran Boeing to send the first crewed rocket to Mars. But these private entities are also working in concert with government players, such as the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Today, roughly 75 nations have a space program of some kind. Only a dozen of those countries have launch capabilities, but they all contribute to the collective push to broaden our capabilities and understanding.

Nations that once viewed each other as mortal foes now collaborate toward mutual ends. American, Japanese, European, and Canadian astronauts live, work, and play with Russian cosmonauts on the International Space Station, which is itself built on international cooperation.

International collaboration has extended beyond low-Earth orbit, too. Robotic missions such as the Cassini mission to Saturn and the Rosetta mission to land a spacecraft on a comet have involved scientists and engineers from around the globe. “This is competition, and at the same time, cooperation,” says space historian David Portree.

Although abundant cooperation is a relatively recent tone for the spaceflight industry, there was a notable instance of collaboration early on in the space era. When politicians made efforts to cool tensions in the early 1970s, US and Soviet officials began to discuss ways to support each other’s astronauts and cosmonauts during emergency situations in space. This led to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project docking mission of 1975. In the middle of the cold war, two Soviet cosmonauts and three US astronauts shook hands in space and collaborated on five joint experiments.

That early willingness to work together in space, despite ongoing political tension on Earth, gives many observers hope that the current spirit of collaboration in space will weather potential political strife in the future.

“In general, I expect we’re going to see more and more cooperation,” Mr. Portree says.