NASA's Parker Solar Probe: a mission six decades in the making

Loading...

In a mission nearly six decades in the making, NASA plans to launch the first probe into the sun’s atmosphere.

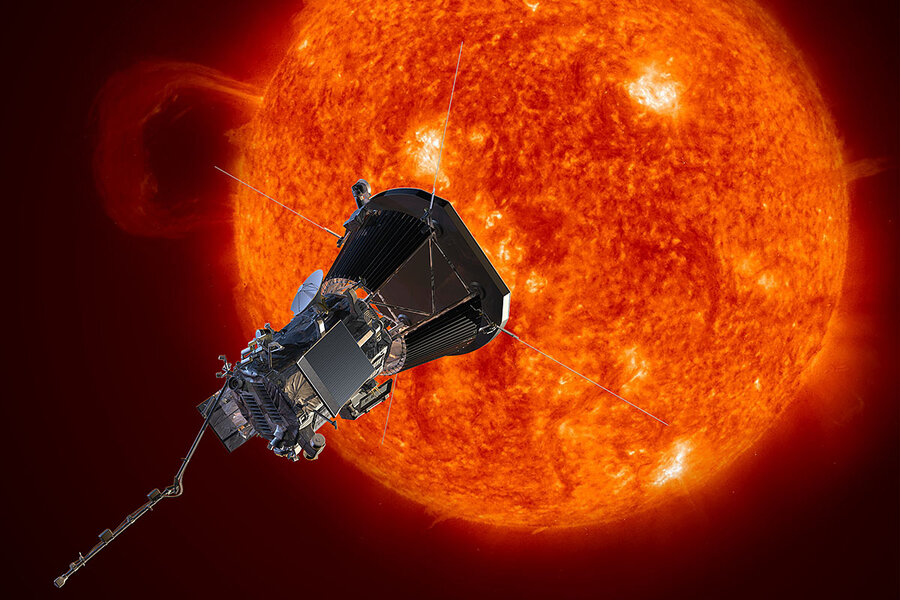

Christened Wednesday morning at an announcement at the University of Chicago, the Parker Solar Probe has been on NASA’s docket since the space agency’s inception. The probe is designed to take two dozen increasingly close plunges into the mysteriously hot corona, the wreath of charged particles emanating from our nearest star, as it passes some 4 million miles off the sun’s surface.

The mission was first conceived in 1958, the year NASA came into existence. It aims to answer longstanding questions about the solar wind, the stream of charged particles that originate in the sun’s atmosphere and flow from the star at millions of miles per hour to far beyond the orbit of Pluto. Getting an up-close look at solar wind near its birthplace could help scientists better predict solar storms that could wreak havoc on power grids on Earth and imperil spacecraft and astronauts in deep space, and could lend insight into the basic processes that govern how stars function.

“This has been a mission that has been planned multiple times over more than 50 years, and now we have the technology to do it,” says Eric Christian, a senior research scientist in the Heliospheric Laboratory at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. “We’re finally at a point in time where we can do this mission that NASA has been wanting to do since its very start.”

Researchers also hope the probe will reveal clues about one of our solar system’s most enduring mysteries: Why, in an apparent violation of everything we know about thermodynamics, temperatures are hundreds of times cooler on the surface of the sun than they are on the corona. NASA heliophysicist Georgia de Nolfo likens this phenomenon to “putting a pan of water on a block of ice and watching the water come to a boil.”

Perhaps more important, the mission promises to bring scientists closer to understanding fundamental processes of our solar system, and of the hundreds of billions of other star systems in the universe.

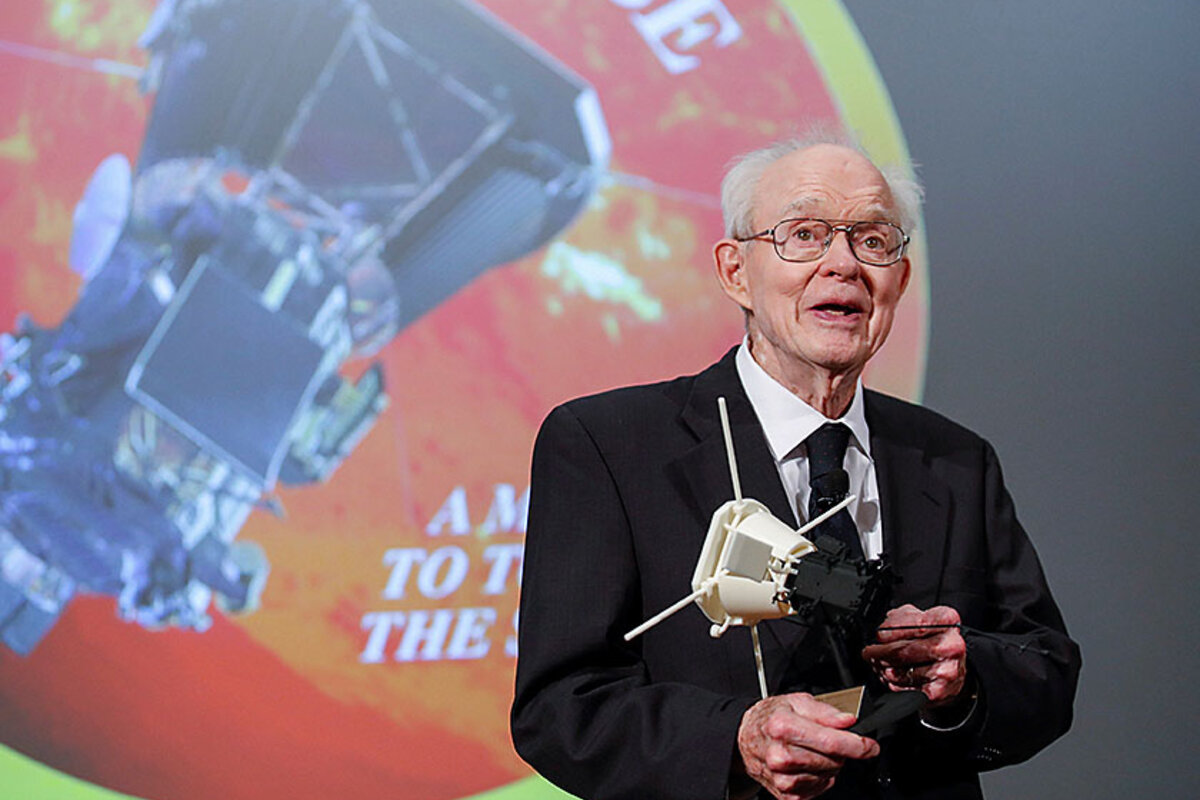

“The sun is a primary puzzle in the universe,” Dr. Eugene Parker, the probe’s namesake and the the University of Chicago physicist who theorized the existence of the solar wind in a 1958 paper, told reporters. “It’s the one star we can observe in detail, and stars are complicated things.”

One key complication researchers have been unable to contend with, until recently, is the searing heat emanating from the sun.

“We’ve never had the technology to allow us to go up and be in the corona and be in that intense heat,” says Nicola Fox, a mission project scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

The Parker Solar Probe’s 7.5-foot-diameter, carbon-carbon composite thermal protection system is the first heat shield capable of withstanding temperatures of up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

Because the probe’s orbit is highly eccentric, the shield has to withstand not just heat, but it also must stand up to vast changes in temperature without cracking. Over its seven-year mission, the spacecraft is scheduled to make 24 increasingly closer passes around the sun, each time swinging back up to the orbit of Venus.

The progress that allowed engineers to build this spacecraft is also what makes its mission so important. “Our increased dependence on technology in space and on the ground makes us more vulnerable to space weather events,” says Dr. de Nolfo.

The solar wind is anything but a steady breeze. Sometimes, our star will belch out intense streams of plasma, known as coronal mass ejections. If those ejections of charged particles interact with our planet’s magnetic field, the resulting electrical current on Earth can overload the transformers on power grids and corrode oil and gas pipelines. Additionally, solar storms can disrupt communications and GPS satellites and could threaten astronauts with radiation. For instance, in 2006, a powerful solar flare forced astronauts aboard the International Space Station to hole up in the airlocks and other heavily shielded areas.

“As we send man further into the solar system and certainly with all our satellites, prediction is really important,” says Dr. Christian.

The possibility of unraveling the fundamental mysteries of the sun, like the coronal heating problem, are just as tantalizing for scientists.

“Understanding how our own sun creates and maintains its atmosphere is a critical step in understanding how other stars maintain their atmospheres and how these atmospheres influence surrounding planets and the potential for life on planets,” says de Nolfo.

A distance of 4 million miles from the sun’s surface may seem like a long way, but this summer, those of us on Earth will get a much better sense of just how close that really is. The Great American Eclipse of August 21, 2017, will afford skywatchers a detailed glimpse of the sun’s corona, unobscured by the blinding light of the sun itself.

If all goes well, the probe will actually be inside that corona. “Even I struggle to think about how close that really is,” says Fox.

“To get within 4 million miles of the surface of the sun is going to be really exciting,” says Christian. “It’s where the solar wind is still being accelerated. It’s where the corona is still being heated. We will be there where the action is, for the first time.”