World's only metallic hydrogen sample disappears, if it indeed existed in the first place

Loading...

The world’s first sample of metallic hydrogen, a form of the element that scientists have long chased only to come up empty handed, mysteriously vanished from the Harvard University lab where it was created last month as researchers sought to conduct further testing on it.

Considered a 'holy grail' of solid-state physics, metallic hydrogen has proved too elusive to create, resulting in failed attempts throughout the past 80 years by various researchers. But the element has extreme value in its applications for conducting energy at a highly efficient rate, spurring many to attempt to create the alluring substance, which requires extremely low temperatures and high rates of pressure to form.

While researchers at Harvard thought they had cracked the code in January, it seems the path forward has been stalled, at least temporarily.

"Basically, it's disappeared," Isaac Silvera, the team’s leader who has worked to uncover metallic hydrogen for decades, told ScienceAlert last week. "It's either someplace at room pressure, very small, or it just turned back into a gas. We don't know."

Dr. Silvera says the sample vanished on Feb. 11, as researchers prepared to pack it up and transport it to the Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago for further testing. At just 0.0015 millimeters thick and 0.01 millimeters in diameter, the hydrogen was thinner than a strand of hair, stored at extremely lower temperatures and at high pressure between two diamonds.

But when pressure caused the diamonds to break, researchers say they lost sight of the sample.

When Silvera’s team announced the discovery last month, it drew wide attention and acclaim. The discovery held revolutionary applications, such as creating ideal electrical wires or rocket fuel.

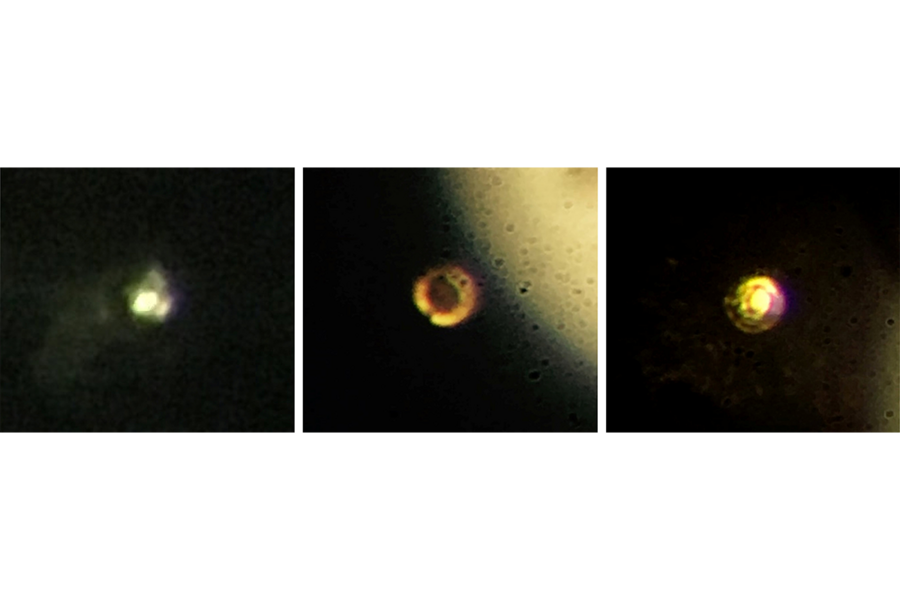

“This is the Holy Grail of high-pressure physics,” Silvera said in a statement released by Harvard at the time. “It’s the first-ever sample of metallic hydrogen on Earth, so when you’re looking at it, you’re looking at something that’s never existed before.”

But the discovery was also met with skepticism by other researchers who took issue with the lack of testing conducted on the material. Without sufficient evidence, many scientists refused to take the study’s findings at face value.

One glaring issue, some say, is that Silvera’s team noted that they observed a shiny material in the cell, but did not track whether hydrogen was present in the sample the entire time.

“Maybe they had something in the first place,” Alexander Goncharov, a staff scientist at the Carnegie Institute for Science in Washington, D.C., told Gizmodo, “but it wasn’t metallic hydrogen.”

Despite the criticism, Silvera remains confident that his team can replicate the results in future experiments.

“This disappearance doesn't say anything about the validity of the sample. Anyone who does high pressure works knows that you have failures like this. The important thing is the measurements that we made of the reflectance, and those are solid,” he told ScienceAlert. “So it's not a setback, it's just a disappointment that we were unable to make more measurements on the sample.”