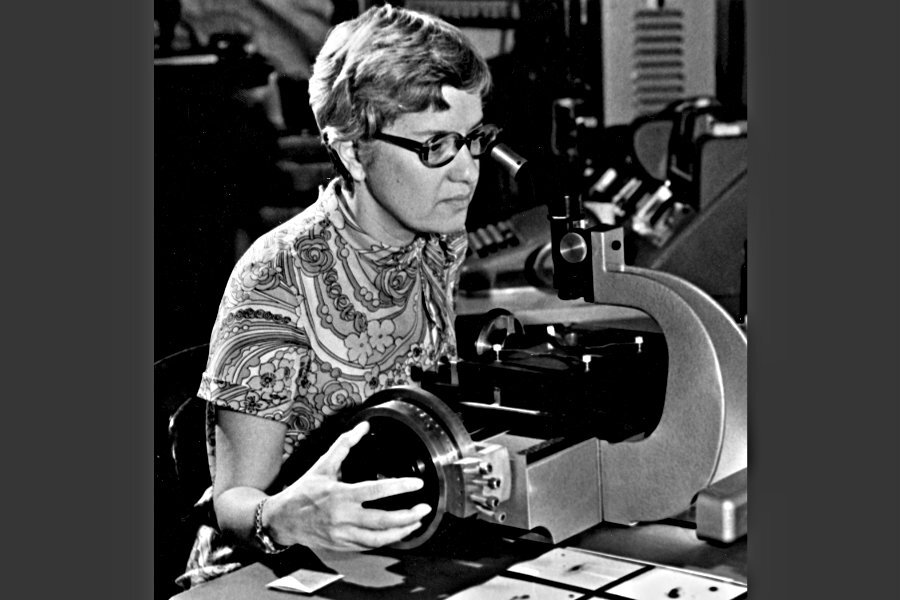

Astronomer Vera Rubin transformed our understanding of the cosmos

Loading...

Vera Rubin was known for her trailblazing contributions to the scientific community, both in the field of astronomy, and in her efforts to open doors for women in science. Her death, on Christmas Day this year, marks a loss for the scientific community.

Dr. Rubin’s best known discovery is her confirmation of the existence of dark matter, a concept was pioneered by Swiss astrophysicist Fritz Zwicky in the 1930s, but was only proved by Rubin in the 1970s.

“The existence of dark matter has utterly revolutionized our concept of the universe and our entire field,” astronomer Emily Levesque told Astronomy Magazine in October. “The ongoing effort to understand the role of dark matter has basically spawned entire subfields within astrophysics and particle physics.”

Born in 1928, Rubin became fascinated by the stars when her family moved to Washington, DC, when she was a child. Her new bedroom’s windows allowed her to stargaze, observing the movement of the stars throughout the night.

At the age of 14, Rubin crafted a telescope out of a cardboard tube. Later, Rubin followed her love of science and the stars to Vassar for an undergraduate degree, and then to Cornell University for a Masters, after being told that Princeton would not accept a woman to its graduate program.

At age 22, the new mother to a month old baby presented her research on the rotation of the universe at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting. The male-dominated crowd was critical – yet she went on, raising four children while earning a doctorate at Georgetown University.

Finally, in the 1960s, Rubin was introduced to research partner, Kent Ford, with whom she went on to confirm the existence of dark matter in the 1970s.

In her own words, Rubin described her work with dark matter to Discover magazine in 2002, saying:

“In a spiral galaxy like our own, a couple hundred billion stars orbit around the center. Spirals appear to thin out toward the edges, so the gravitational pull on the outer stars should be weaker out there. Everyone therefore assumed that objects near the edges orbit more slowly. But that is not what I found: Even stars at the periphery are orbiting at high velocities. There has to be a lot of mass to make the stars orbit so rapidly, but we can't see it. We call this invisible mass dark matter.”

Rubin’s work with dark matter has informed decades of astronomical and scientific inquiry into the nature and composition of the universe. Scientists say that her contributions cannot be overestimated.

Yet for all her pioneering work, both on dark matter and on other topics, Rubin was never awarded a Nobel Prize. Given the groundbreaking nature of her discoveries, many attribute her Nobel snub to long-held gender biases in the scientific community, biases that Rubin fought hard against.

“She frequently would see the list of speakers [at a conference],” Princeton University’s Neta Bahcall told Astronomy magazine this year, “and if there were very few or no women speakers, she would contact [the organizers] and tell them they have a problem and need to fix it.”

Rubin’s former colleagues have shared dozens of stories about her advocacy for women in science over the years, from tales of Rubin conducting research at her own dining room table while taking care of her children, to stories of the time she created a women’s restroom at the then male-only Palomar Observatory outside of San Diego.

When asked about her advice for women who hoped to pursue scientific careers, Rubin said this in 2002:

“I guess I would say that if they really want to do it, to just go ahead, try not to let anything discourage them, try not to quit, but to recognize that academia is still not kind to women.”

Rubin is survived by three of her four children, all of whom have advanced degrees.