Space station's new door swings open to welcome commercial travellers

Loading...

Astronauts created a back door for the International Space Station (ISS) on Friday, which will someday enable commercial space shuttles to dock.

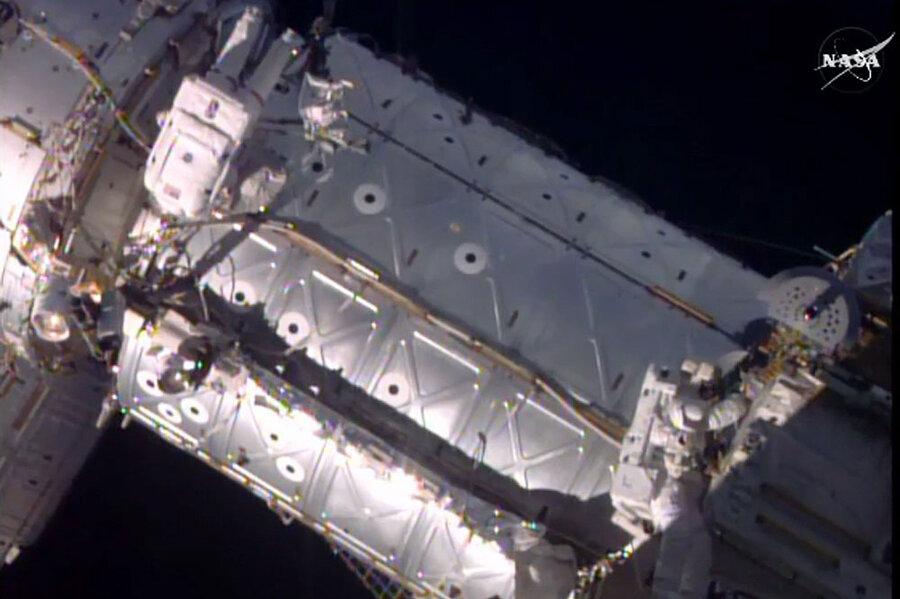

During a spacewalk on Friday, NASA's Commander Jeff Williams and Flight Engineer Kate Rubins installed the first of two docking adapters where crews riding with Boeing and SpaceX will soon disembark.

The newly named "international docking adapter's" installation marks another step forward in commercial space travel, where steadily advancing technology in the last two years has opened up real potential for life both here and in the skies.

"It's really good we have an international standard now that anybody can build against and come dock to the station or to anything that has the same standard," David Clemen, Boeing's development director for the space station, said in a NASA press release.

The dock uses unprecedented open-source technology so anyone can build to it. This design strategy hints at how space travel will operate as it enters a new era of commercial development.

"A new interface standard out in the public domain for anyone to build to that standard will stimulate competition and stimulate technology," NASA program manager Shaun Kelley said in an interview on NASA TV. "We're entering a commercial sector now. Any company in the world, any country in the world, can build to that standard and be sure that they can be compatible with us."

The adapter precedes NASA's shift from transporting ISS-bound astronauts via Russian Soyuz rockets, as it has done since 2012, to a new model of using US commercial shuttles. Switching to US companies Boeing and SpaceX frees NASA from an expensive transportation plan with Russia that costs taxpayers $70 million per ride. Set for 2018, the plan suggests how soon commercial space travel could become a reality.

"Never before in the history of human spaceflight has there been so much going on all at once," said John Elbon, the vice president and general manager for space exploration at Boeing, during a 2015 briefing on NASA's commercial crew program.

Space travel operations are already speeding up back on terra firma. One sign of the uptick is the packed 2016 schedule for Cape Canaveral, where private companies, the military, ISS cargo loads, and NASA operations are jostling for time on the launch pad. Private space companies such as SpaceX and United Launch Alliance planned more than 30 launches from Florida alone in 2016, nearly double the 2015 schedule.

"The last time we saw 30-plus launches would have been back in the 1960s," Dale Ketcham of the Space Florida economic development agency told Reuters.

The advance is not without complications. Some space observers on the international scene expressed dismay after Congress passed a bill in late 2015 to regulate space mining, betting that travel and exploration will soon fall under the purview of US companies, not just governments. Some said the law violates the universalist spirit of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and needs further discussion, wrote Jeff Foust for the Space Review.

"Asteroid mining is cool. Everyone thinks it's cool. But is it legal?" asked Jim Dunstan, founder of the Mobius Legal Group, during a May panel on the issue. "These are the tough scenarios that we’ve really got to work through as we talk about policy," he said, according to Space Review.

But technology's rapid advance will bring those "tough scenarios" to the forefront quickly in the coming years. For example, after many failed attempts, companies are learning to reuse rockets in a cost-effective manner, as the Christian Science Monitor's Pete Spotts previously reported:

NASA's space shuttle program was an initial attempt at developing a fleet of reusable vehicles for human spaceflight, as well as for launching and servicing satellites. But over its 30-year history, it never delivered on its architects’ initial promises.

Initial estimates suggested that each flight would cost as little as $9 million and the cost of carrying cargo would be $118 per pound. By the end of the program, each flight cost about $1.5 billion, and cargo cost about $10,000 per pound.

Now, privately-owned aerospace companies owned by wealthy visionaries are taking up the challenge, free of Wall Street demands for quick returns on investment or of the intense scrutiny of annual federal budget cycles.

As technology makes space exploration appear more practical, some also see the economic potential that Star Trek's iconic "final frontier" could offer to our already-mapped planet. Moon Express, an entrant in the Google Lunar XPRIZE competition, expresses the commercial aim of many companies seeking to explore the moon's natural resources to facilitate deeper space travel.

"We believe it's critical for humanity to become a multi-world species and that our sister world, the Moon, is an eighth continent holding vast resources than can help us enrich and secure our future," writes Moon Express on the prize website.