How methane rivers carved deep canyons into Saturn's moon Titan

Loading...

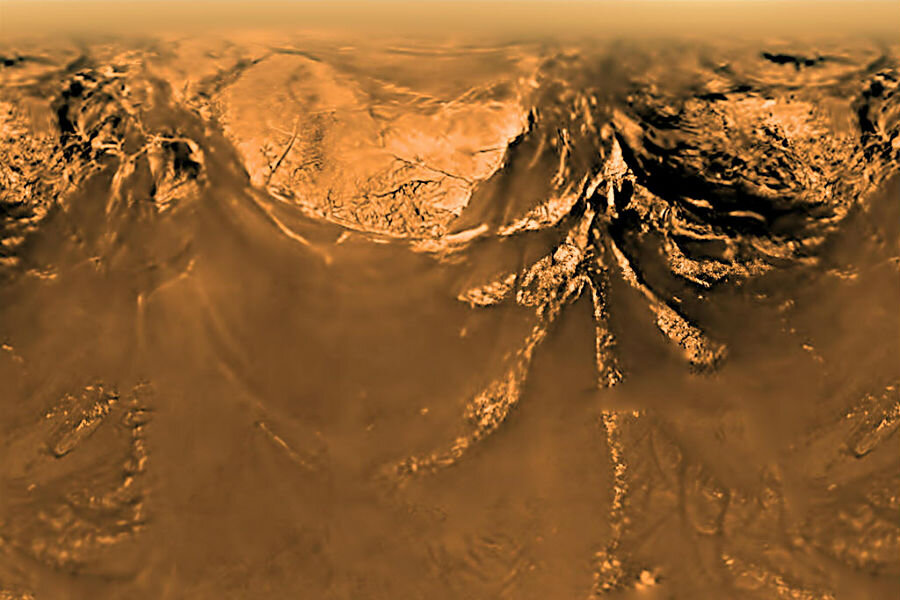

Much like the water that carved Earth’s Grand Canyon over millions of years, liquid hydrocarbons have cut a network of canyons on Saturn’s moon of Titan, a new study of radar images captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 2013 has found.

"Earth is warm and rocky, with rivers of water, while Titan is cold and icy, with rivers of methane. And yet it's remarkable that we find such similar features on both worlds," Alex Hayes, a Cassini radar team associate at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

The study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters Tuesday, is the first direct evidence that confirms flowing methane carved the deep, steep canyons on the moon’s surface. The radar images also indicate some of the canyons could still contain liquid hydrocarbons that continue to carve away at them.

Cassini captured the images in May 2013 by focusing its radar instrument on channels that flow into Ligeia Mare, a methane lake the size of Lake Superior found near the moon’s north pole. The researchers that studied the radar images discovered a network of narrow canyons they dubbed Vid Flumina. The canyons are each less than a half-mile wide, but have slopes steeper than all but the steepest ski slopes. The canyons are also 790 feet to 1,870 feet deep.

The canyons’ depth and steepness show the process that created them occurred over a long period of time or eroded the canyons’ surfaces much faster than other parts of Titan. This could have occurred because the terrain was once at a high elevation (like the process that formed the Grand Canyon), or quickly dropped to the moon’s sea level (like the process that formed Arizona’s Lake Powell).

"It's likely that a combination of these forces contributed to the formation of the deep canyons, but at present it's not clear to what degree each was involved," Valerio Poggiali, lead author of the study, in the statement. But Mr. Poggiali of the University of Rome added that the discovery points to the need to study Titan’s geology more.

“What is clear is that any description of Titan's geological evolution needs to be able to explain how the canyons got there,” said Dr. Poggiali, in the NASA statement.

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery of these images is the "glint" Cassini found inside some of the canyons. The smooth surface the glint reveals suggests liquid hydrocarbons remain in some of the canyons, showing further similarities between Earth and Titan. While liquid likely carved canyons on Mars, too, Earth and Titan are the only two worlds in the solar system known to still harbor stable liquids, according to Space.com

Launched into space in 1997, Cassini has provided scientists their first close look at Saturn, its rings, and its moons. Since Cassini arrived there in 2004, it has made other discoveries that point to Titan’s similarities to this planet, according to the International Business Times. Some of these discoveries have given scientists a glimpse of how Earth looked millions of years ago. Others, like the "Magic Islands," have similar geological processes to those on Earth. A kind of tidal cycle causes the Brigadoon-like "islands" to disappear into Ligeia Mare, the moon's second largest sea, which the Vid Flumina canyons flow into, as Pete Spotts wrote for The Christian Science Monitor in 2014:

These vast reservoirs of liquid hydrocarbons are centered around the moon's north pole region, where they are thought to play a key role in the moon's equivalent to Earth's water cycle. In Titan's case, it's the methane cycle, where the liquid methane at the surface of the lakes and seas evaporates, rises to condense as clouds, then returns to the surface as methane rain. Liquid methane flows in to streams and rivers, sculpting the moon's surface on their return to lakes and seas.