A surprise in our galaxy: a vast tract of space with no young stars

Loading...

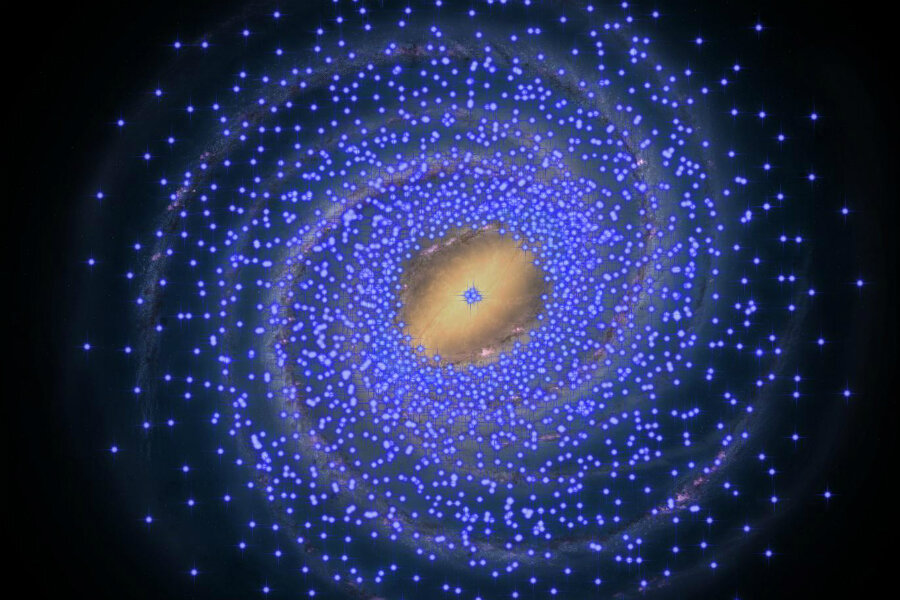

At the center of our galaxy, in what’s called the inner disk, astronomers have discovered a stellar retirement community.

An international team of researchers have detected a vast tract of space where there are no young stars. The region, described Monday in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, begins several thousand light years from the center of the Milky Way.

Researchers say their findings challenge current theories on galaxy formation.

"The current results indicate that there has been no significant star formation in this large region over hundreds of millions years,” said co-author Giuseppe Bono, a scientist at the Astronomical Observatory of Rome, in a statement.

By observing the distribution of stars throughout our galaxy, the Milky Way, astronomers can begin to understand how it formed and developed. And Cepheids, which are young stars that periodically pulsate in brightness, make useful growth markers. Based on the duration of bright periods, astronomers can estimate the distances between star regions.

But the Milky Way is thick with light-blocking cosmic dust, so it’s difficult to identify Cepheids in the inner reaches of the galaxy. A research team led by Noriyuki Matsunaga, a professor of astronomy at the University of Tokyo, used near-infrared data from South Africa’s InfraRed Survey Facility (IRSF) telescope to peer through the haze.

Previous research has identified Cepheid stars at the very heart of the Milky Way, so Professor Matsunaga and his colleagues were surprised when they found virtually no Cepheids in the region just outside the center, about 8000 light years out.

"Our conclusions are contrary to other recent work, but in line with the work of radio astronomers who see no new stars being born in this desert,” said co-author Michael Feast, a professor of astronomy at the University of Cape Town, in a statement.

Other studies, some dating back decades, have supported the idea of limited star formation in the galaxy’s inner disk.

“I can't say I'm too surprised,” says Dan Clemens, a professor of astronomy at Boston University, in an email to The Christian Science Monitor. “Back in the 1980s, many studies found that the reservoir of molecular hydrogen gas needed for forming new stars showed a distinct dip out to three [kiloparsecs] – similar to the 8000 [light years] of today's reports – from the center of the galaxy.”

The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy – a swirling disk of gas and cosmic dust. When spiral galaxies grow and collect mass, orbiting stars may cluster in the shape of a bar at the center. Some researchers suggest that the galaxy’s center is surrounded by a “molecular ring” of dense, star-forming gas. The ring, Dr. Clemens says, may be “driven or mediated” by the stellar bar.

“The bar might play key roles in preventing molecular gas from accumulating into sizeable clouds or forming new stars,” Dr. Clemens says, “at least compared to the much higher rates for both that exist within the molecular ring and beyond the bar.”

Whatever the reason, researchers note that even the absence of Cepheid stars can offer new insights into the galaxy we call home.

“The movement and the chemical composition of the new Cepheids are helping us to better understand the formation and evolution of the Milky Way,” said Dr. Bono.