Is NASA ready for a human mission to Mars? No, say government auditors.

Loading...

NASA has taken bold steps toward crewed Mars exploration in recent years. But according to a new audit, the agency may be moving too hastily.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) expressed concerns this past week about the feasibility of NASA’s Orion crew capsule and Space Launch System (SLS). In two government-requested audits, the GAO questioned NASA’s ability to meet program deadlines, citing insufficient funding and internal management issues.

“The main problem is that we do not have a clear long-term goal for the national human spaceflight program,” says Mike Gruntman, a professor of astronautics at the University of Southern California, in an email to The Christian Science Monitor. “Being rudderless does not help in bringing public excitement and support.”

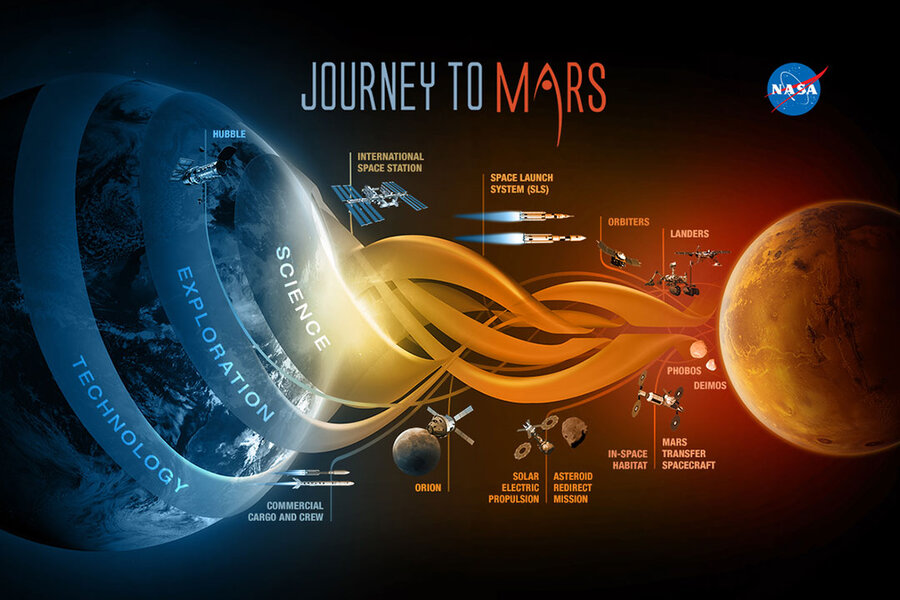

NASA’s “Journey to Mars” initiative has been a source of both excitement and controversy. The Asteroid Redirect Mission, in which the agency will send four astronauts to redirect an asteroid into the moon’s orbit, is slated to launch sometime in the next decade. The mission is designed to test new propulsion technology for future crewed Mars missions. In the 2030s, NASA hopes to send an Orion crew to the red planet.

NASA plans to complete the first SLS launch in 2018. In the test mission, called Exploration Mission 1, the rocket will carry an empty Orion into orbit around the moon. In subsequent missions, SLS/Orion will launch with a full crew. NASA has scheduled Exploration Mission 2 for April 2023, but administrators hope to launch as early as 2021.

According to the GAO, however, the agency’s schedule just isn’t realistic. By pushing for earlier launch dates, NASA is increasing the inherent risk of a deep space mission. NASA’s budgeting practices are also scrutinized in GAO’s audit. In September, the agency asked for $11.3 billion to prepare Orion for launch.

“Ideally, if these programs go forward, NASA would be taking actions to reduce the risks we see now, which are being caused by management issues,” says Cristina Chaplain, who led the GOA audit, in an interview with the Monitor. “They’re going to face the technical issues no matter what. But they’re exacerbating them with management concerns, like not having accurate cost estimates.”

In February, the US House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology convened to discuss NASA’s long-term goals. Members argued that the agency lacked clear direction when it came to Mars exploration. The committee, which is composed mostly of Republican congressmen, also raised concerns about the cost of a crewed Mars mission.

When the cold war was in full swing, competition with the Soviet Union was an effective motivation for US space travel. As a result, the Apollo missions and other subsequent programs met little resistance in terms of funding and public support. By comparison, today's Congress has been critical of NASA’s more ambitious initiatives over the last few decades.

In some ways, the glory days of of Apollo-era space travel are over. But in other ways, NASA is simply facing the same challenges it always has.

“By the middle of the ’60s, Congress is already growing very restive at spending billions of dollars on the Apollo program when there are very profound problems down here on Earth,” says Peter Westwick, a Space Age historian at the University of Southern California, in a phone interview with the Monitor. “NASA has always faced this problem: How do you justify spending a lot of money to explore space?”

According to some experts, the US space program was politicized from the outset – and that’s the way it should be.

“Yes, there’s the counter-argument that the NASA budget is just a fraction of a percent of the federal budget,” Professor Westwick says. “But when you’re talking about billions of dollars, then it becomes not just a technical decision, but a political decision as well.”

But Chaplain isn’t concerned with the politics of space travel. It’s not that NASA’s plans for Mars exploration are premature, she says, just that clearer direction will be essential going forward.

“First of all, we need a clear sense of where we’re going and when,” Chaplain says. “We don’t have that from the administration or Congress. There’s no, ‘Hey, we’re going to the moon in 10 years.’ We need that kind of goal set, and then we can decide if the path we’re on is the right one.”

“We don’t even know what the path is at this point,” she adds. “All we have are these two programs that represent the beginning of something that will eventually lead to a long-term effort.”