Mars rover gets an upgrade and a new trick: self-guided laser shots

Loading...

NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity just added another trick: autonomous laser shooting.

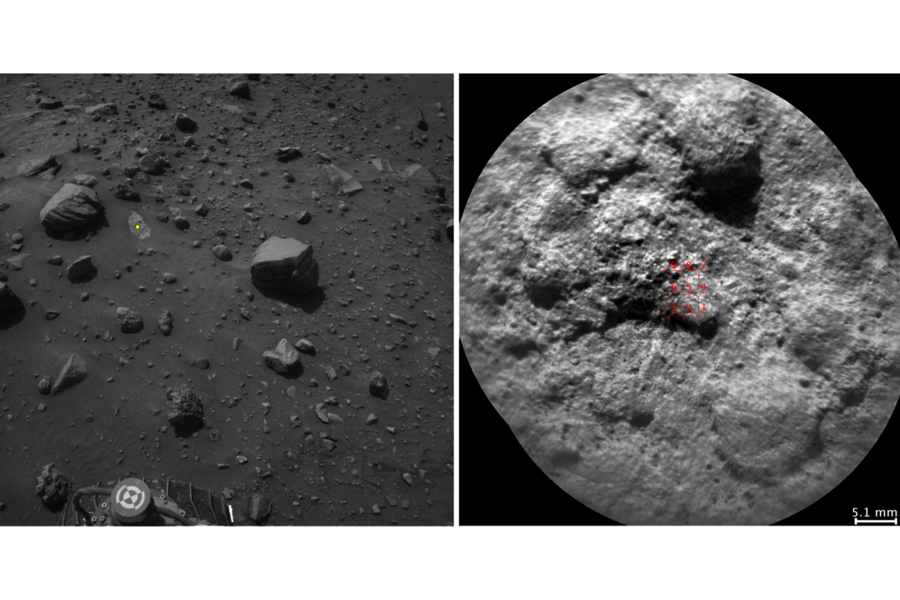

For the first time ever for a robot planetary mission, Curiosity can autonomously target potentially interesting rocks and soil, shoot a laser and camera at the objects through the rover’s ChemCam, and send the information tens of millions of miles back to Earth.

Before now, scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calf., would select samples from Curiosity’s images and manually direct the ChemCam to specific areas. Scientists here on Earth will still select the majority of samples, but “the autonomous targeting adds a new capability,” explains NASA.

The new developments are possible through Autonomous Exploration for Gathering Increased Science (AEGIS) software. AEGIS analyzes images of Curiosity’s surroundings by NASA-set criteria, such as rock size – from up to 23 feet away – and then decides whether or not to shoot the ChemCam.

“This autonomy is particularly useful at times when getting the science team in the loop is difficult or impossible – in the middle of a long drive, perhaps, or when the schedules of Earth, Mars and spacecraft activities lead to delays in sharing information between the planets,” Tara Estlin, leader of the AEGIS project at JPL, says in a press release.

During its four Earth-years on Mars, Curiosity has fired over 350,000 lasers to examine more than 1,400 specimens.

Scientists also say the development will be especially helpful in keeping Curiosity’s mission up to date. Each time the rover ends a drive, Curiosity uses its Navigation Camera (NavCam) to send a photo of its location to Earth. But now AEGIS can direct a ChemCam image itself, sending information to NASA before the NavCam images have even reached Earth.

“This gives the team an extra jump in assessing the rover’s latest surroundings and planning operations for upcoming days,” explains JPL.

But this doesn’t mean NASA scientists will now leave Curiosity to function on its own.

“AEGIS brings an extra opportunity to use ChemCam, to do more, when the interaction with scientists is limited,” says Olivier Gasnault, the ChemCam Science Operation lead at France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), in a press release. “It does not replace an existing mode, but complements it.”

Even before its self-initiated laser system, Curiosity has been an instrumental part of NASA’s Mars study.

On May 11, Curiosity completed its second Martian year on the red planet, the equivalent of 687 Earth days. During this time, Curiosity has discovered information about Mars’ rhythm of seasons, temperature fluctuations, and orbit shape.

And last month, NASA’s Curiosity rover made news by discovering evidence of silica-rich volcanic materials in Gale Crater, an area the rover has been exploring since 2012.

NASA announced its future plans for the red planet on Monday, in which the space agency commissioned five aerospace companies to conceptualize a future Mars orbiter mission. NASA plans to land humans on Mars by the 2030s.