What can amber-encased baby bird wings say about prehistoric flight?

Loading...

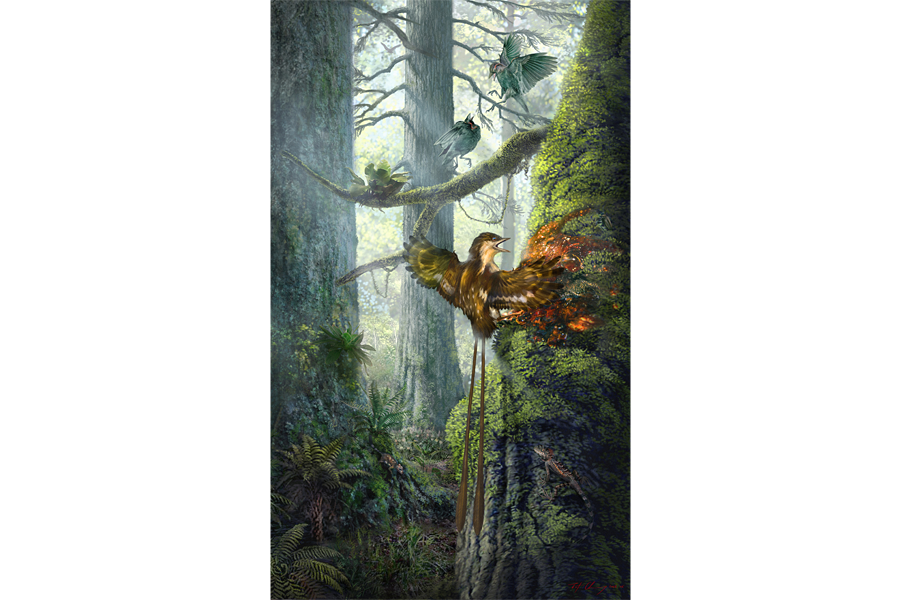

Dinosaurs were roaming the Earth and flowering plants were just beginning to flourish when two tiny baby birds lived their short lives.

These walnut-brown, toothed hatchlings hadn't grown larger than today's hummingbirds when they encountered wads of sticky, goopy tree resin. Perhaps the newborn enantiornithes were taking their first flights, stumbling out of a nest, clambering around the treetops, or maybe they fell into the sticky trap when a wing became ensnared in the resin and the little birds weren't able to pull it loose.

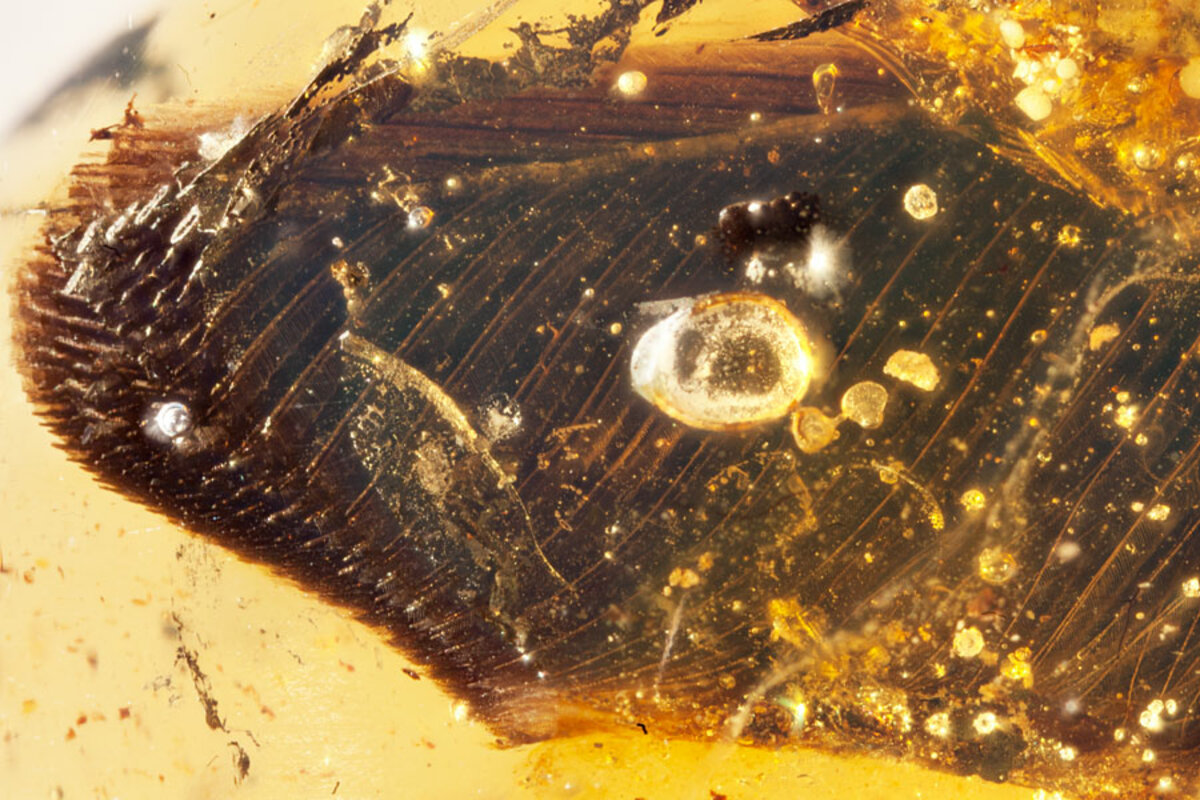

Now, 99 million years later, that resin has hardened into amber around those tiny wings, preserving them, bones, tissue, feathers and all. And these golden fossils are offering scientists a glimpse back in time.

"Enantiornithines, these strange, toothed birds, had plumage that looked a lot like adult bird plumage, even when they were just hatchlings," says Ryan McKellar, curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum who helped analyze the new fossils for a paper published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

Looking at the bones of these amber-encased wings, the scientists were able to tell that these birds were quite young. But their adult-like feathers suggested these tiny hatchlings may have been able to fly "right out of the egg, or right out of the nest," Dr. McKellar tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview.

"They were ready for action as soon as they hatched," lead author Lida Xing, of China University of Geosciences in Beijing, said in a press release. "These birds did not hang about in the nest waiting to be fed, but set off looking for food, and sadly died perhaps because of their small size and lack of experience."

When you think of fossils you might picture a compression fossil, in which an animal's skeleton has been preserved in a layer of sedimentary rock. Occasionally the tissues, fur, or feathers of an animal leaves some sort of imprint in the rock around the bones.

"The problem we face there is that more often than not it's a sort of tangled mess," McKellar says. "It's hard to pick out the finer details of the feathers within this mat, or carbon film."

That's where amber fossils come in. As tree resin turns into amber over time, it preserves an organism in place, tissue and all. The resin contains natural preservatives, entomologist George Poinar, known for studying amber fossils, previously explained to the Monitor.

"Amber can be a really valuable supplement to these compression fossils" because it can preserve animals in such lifelike detail, McKellar says.

In life, these little birds had walnut-brown coloring on the upper side of their wings, with a paler band running across their wings. The wings' underside was very pale, perhaps even white. Two long, ribbon-like tail feathers trailed behind the tiny birds' bodies. In their beaks, these young enantiornithines had teeth, hinting at their dinosaur ancestry.

"They're thought to be some of the closest relatives to modern birds," McKellar says. Today enantiornithines are extinct.

"The fact that well-preserved plumage is now being found in 100-million-year old amber is remarkable, and very cool, but the [new] information in these two specimens is limited," Luis Chiappe, director of the Dinosaur Institute at the National History Museum of Los Angeles County who was not part of this study, tells the Monitor in an email.

"Fossils that are 25 million years older than these amber pieces (i.e., fossils from 125 million year old rocks in Spain and China) provide the same information about the plumage of enantiornithines: differentiation among the wing feathers (alula, secondaries, primaries, and coverts) as well as details of their color patterns."

"The authors are correct to highlight the high degree of development of the feathers and how the presence of fully formed flight feathers in hatchlings suggest a high degree of precociality," the extent to which a young organism shows mature features and behaviors, such as mobility. But "this has already been mentioned, many times, based on the presence of similar feathers in traditional fossils as well as osteological studies correlating bone formation (ossification) with precociality," Dr. Chiappe says.

McKellar agrees that these fossils confirm previous descriptions of enantiornithines based on compression fossils. But he hopes that this study will encourage scientists to turn to amber fossils more readily to find new insights into ancient organisms.

These chunks of amber are about the size of ping-pong balls, McKellar says. And the wings embedded in this amber are just fragments, a few bones of the tip of the bird's wing with feathers fanning across them.

"It can be really difficult working with these specimens because a lot of the feathers are overlapping each other," he says. "In one of the specimens they're nicely splayed out, but in the other, they're actually piled on top of each other, so it's hard to tease out details."

McKellar, who used strong lighting and magnification to peer into the amber fossils at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, says, "it's just sort of a mass of brown in the specimens until you get the right light on them."