What can these baby alien planets teach us about planetary formation?

Loading...

Astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets using NASA's Kepler space telescope. But two new celestial bodies are unlike any seen before: They're just a few million years old, veritable planetary infants.

"At 4.5 billion years old, the Earth is a middle-aged planet – about 45 in human-years," Trevor David, an astronomy graduate student at the California Institute of Technology, said in a press release.

Mr. David is the first author of a paper published Monday in the journal Nature that reports the finding of an exoplanet dubbed K2-33b, thought to be 5 to 10 million years old. "By comparison" to Earth, he said, "the planet K2-33b would be an infant of only a few weeks old."

And the other exoplanet, announced in another Nature paper this Monday, which orbits a star called V830 Tau, is thought to be even younger, just 2 million years old.

"This discovery is a remarkable milestone in exoplanet science," Erik Petigura, a postdoctoral scholar in planetary science at the California Institute of Technology and a coauthor on the paper on K2-33b, said in the press release. "The newborn planet K2-33b will help us understand how planets form, which is important for understanding the processes that led to the formation of the earth and eventually the origin of life."

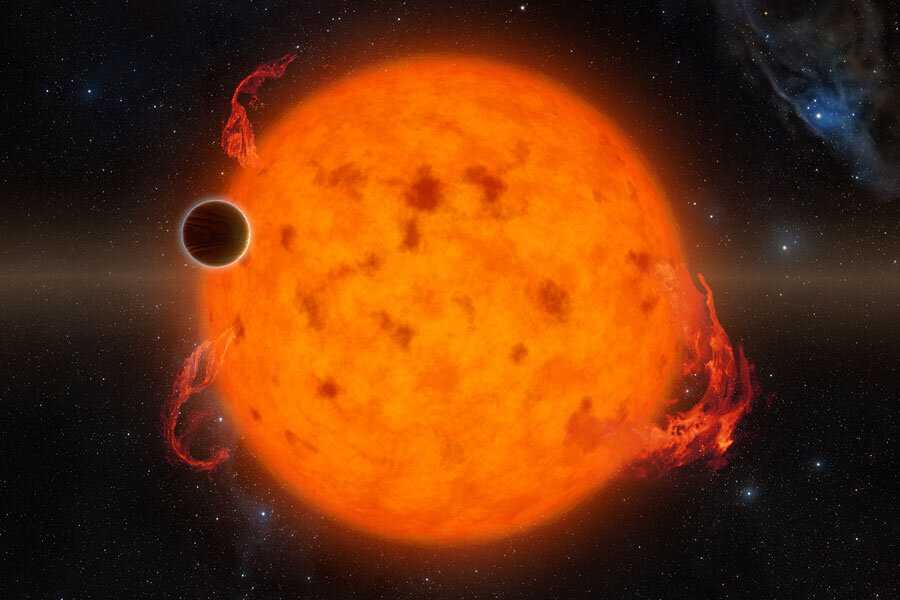

Planets are born of the dust and gas that whirls around young stars as they form. That dusty region forms a protoplanetary disk. Over the first few million years of a star's lifetime, that material coalesces into rocky planets, gas giants, asteroids, comets, and other celestial bodies.

Because of the young age of the newly identified exoplanets, their solar systems could be good candidates to study planetary formation in action.

And these new exoplanets could shed light on one particular planetary mystery: the "hot Jupiter."

Both K2-33b and the V830 Tau exoplanet are large like the gas giants in our solar system, like Jupiter. But, unlike Jupiter and our gas giants, these young exoplanets orbit their host stars remarkably tightly.

K2-33b, which is estimated to be 5.8 times as wide as Earth, or about 50 percent larger than Neptune, is so close to its star that it takes just about 5.4 days to make a full orbit. The V830 Tau exoplanet, about 77 percent of the mass of Jupiter, orbits its star in just 4.9 days. By contrast, Jupiter takes about 11.9 Earth years to orbit our Sun.

"These planets presumably form in the outer part of the primordial disk from which both the central star and surrounding planets are born, then migrate inward and yet avoid falling into their host star," the authors of the V830 Tau study write in their paper. "It is, however, unclear whether this occurs early in the lives of hot Jupiters, when they are still embedded within protoplanetary disks, or later, once multiple planets are formed and interact."

Or perhaps "hot Jupiters" can form "in situ," or in place, close to a star, the authors of the K2-33b paper suggest.

"After the first discoveries of massive exoplanets on close orbits about 20 years ago, it was immediately suggested that they could absolutely not have formed there, but in the past several years, some momentum has grown for in situ formation theories, so the idea is not as wild as it once seemed," David said in a NASA press release.

"The question we are answering is: Did those planets take a long time to get into those hot orbits, or could they have been there from a very early stage? We are saying, at least in this one case, that they can indeed be there at a very early stage," he said.