Faint, distant galaxy offers clues of a universe 'dark age'

Loading...

Researchers have glimpsed the faintest early-universe galaxy ever discovered.

Using special telescopes and innovative observation techniques, a research team was able to glimpse a galaxy so dim and small it lies on the very edge of what is currently visible to humans. On Monday, the team, led by physicists from the University of California, Davis, released their findings on the galaxy and how they spotted it.

And although the galaxy may be faint, small, and far away, it could fill in big blanks about one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy: the cosmic "dark ages."

That's the period of time after the Big Bang and before galaxies were able to form, explains Prof. Zoltan Haiman of Columbia University, who is not related to the recent study, in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “The universe was literally dark.”

Scientists theorize that after the Big Bang event occurred, radiation from the blast cooled as the universe expanded. Hydrogen atoms and protons combined to make the universe opaque and dark.

A few million years later, stars and the galaxies around them started forming. The early stars produced ultraviolet light that could ionize the hydrogen in the universe – a process called cosmic reionization.

“Once a sufficient number of stars formed, they started emitting radiation, like the sun,” Professor Haiman explains. “The universe lit up, like when you look at the sky now and see bright dots.”

But there's a fundamental mystery to the cosmic dark ages: If we add up all the galaxies and stars currently visible to humans, they don't provide enough radiation to ionize all of the hydrogen in the universe.

So if there aren’t enough stars to cause reionization, what did?

“The obvious, most natural explanation by Occam's razor is that the reionization was done by more numerous, fainter galaxies we have not discovered yet,” Haiman says.

That’s where the recently detected galaxy provides fresh insight.

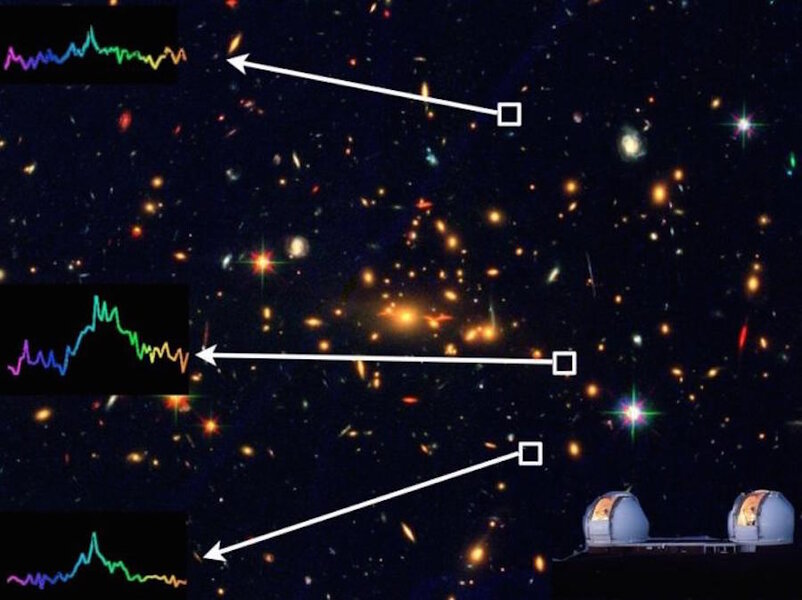

The galaxy would normally have been too faint to detect, but researchers used a technique called gravitational lensing. Predicted by Albert Einstein, the technique makes it possible to magnify an object by relying on the distortion of light from the gravity of an object in front of it.

The faint galaxy recently detected is behind galaxy cluster MACS2129.4-0741. Scientists were able to use gravitational lensing, in combination with the extremely sensitive telescopes at W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, to view it.

The earliest galaxies formed in the universe are still likely too dim for humans to detect, even via gravitational lensing, but finding this faint galaxy is a step in the right direction. Studying it will allow scientists to learn more about the nature and size of early galaxies and how they produced the radiation to reionize hydrogen.

“This galaxy is exciting because the team infers a very low stellar mass, or only 1 percent of 1 percent of the Milky Way galaxy,” said Marc Kassis, staff astronomer at the Keck Observatory. “It’s a very, very small galaxy and at such a great distance, it’s a clue in answering one of the fundamental questions astronomy is trying to understand."