What did it take to be giant 1.56 billion years ago?

Loading...

Today the largest living things on Earth include blue whales, redwood trees, and a 2.4 mile-long fungus in Oregon. But 1.56 billion years ago, the competition for hugeness was on a different scale.

Fossils discovered in northern China represent the largest macroscopic eukaryotes known to live on Earth during that time, according to a paper published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. And you could probably hold them in your hand.

The fact that the authors note that this organism was macroscopic might tell you something about just how little competition it had to be an impressive size. Sure, these prehistoric sea-dwelling plants could be seen by the naked eye, but they clock in at just over 11 inches long at the longest.

"If you choose your time well, you could be a giant," study coauthor Andrew Knoll, the Fisher professor of natural history and a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University, tells The Christian Science Monitor with a laugh.

And not only were these plants giants of their time; they also were big before others. Most multicellular eukaryotes didn't reach this size until just before the Cambrian explosion, about 1 billion years later.

Many of the other similar organisms that scientists have identified as living around 1.56 billion years ago are much smaller than these plants. Some were the size of a thread and others could be covered by a quarter.

Although these ancient seaweeds weren't the only multicellular organisms on the planet at the time, these new fossils could yield fresh insights into the spotty record of early eukaryotic evolution.

Eukaryotes – organisms that, like us, have cells with a nucleus and other complex structures – first began to emerge over 2 billion years ago. But at the time, they were still just single-celled organisms swimming around.

So scientists have long pondered how eukaryotes went from these itty-bitty cells to larger multicellular organisms.

Between this find and previous multicellular fossils from the time, "we are building a modest inventory of simple multicellular organisms at this point," Dr. Knoll says. "This discovery, along with others, says that, whether that jump from single-cells to simple multi-cells was simple or hard, it happened more than once by the time we first see these things."

Furthermore, these organisms might have been photosynthetic.

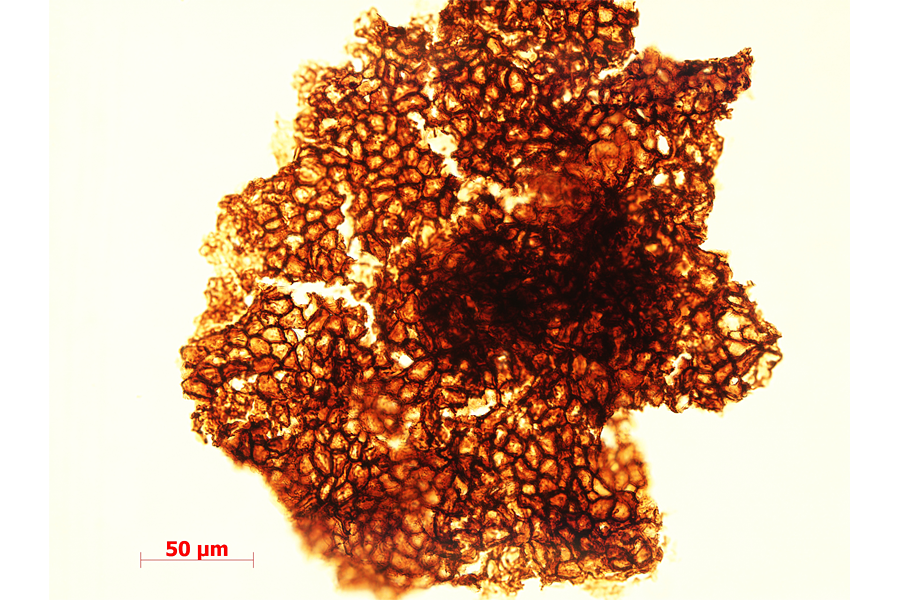

The fossils tell of a leaf-like chunk of plant matter. They look like big, flat, blade-shaped leaves much like some tropical houseplants alive today, Knoll says. That blade-shaped structure suggests the plant may have derived energy from the sun's photons.

"There has been a lot of discussion and debate as to when photosynthesis came to eukaryotes," Knoll says. "This suggests that photosynthesis came pretty early in the history of the group."

It's likely that the first photosynthetic eukaryote was a single-celled organism that took in a cyanobacterium, explains S. Blair Hedges, director of the Center for Biodiversity in the Science Education and Research Center at Temple University, who was not part of this study. This symbiotic event, which Dr. Hedges's research suggests happened 1.6 billion years ago, would have kicked off the evolution of photosynthesis in eukaryotes.

"Biologically, this is really neat because it sets the origin of photosynthesis in eukaryotes all the way back to 1.6 billion years ago," Hedges tells the Monitor. "And that's almost back as far as the beginning of eukaryotes, which is estimated to be around 2 billion years ago."

One thing that is surprising about this find, says Knoll, is that these organisms were even preserved. "They don't preserve under most sedimentary circumstances," he explains. "So what one needed was simply a place where basically these populations were just inundated and buried in an instant and then preserved."

Prehistoric muds that eventually formed shale now in China provided just such an environment. And that's just where Knoll's Chinese colleagues found these new organisms.

These new fossils are part of the history of life, says Knoll. Although large vertebrates like dinosaurs gain a lot of attention in that story, these early multicellular eukaryotes are key pieces too.

"This is something that is in some ways a lot more fundamental than a dinosaur," Knoll says. "This tells you that the building blocks from which the complexity of life that we see today were already in place well over a billion years ago, and almost a billion years before we see the kind of complexity of animals take shape."