'Squishy' exoplanets with wonky orbits shed light on formation of 'hot Jupiters'

Loading...

"Hot Jupiters" were once thought to be weird outliers among exoplanets. But as thousands of exoplanets have been spotted over the last decade, scientists have come to realize the hot gas giants are actually quite common.

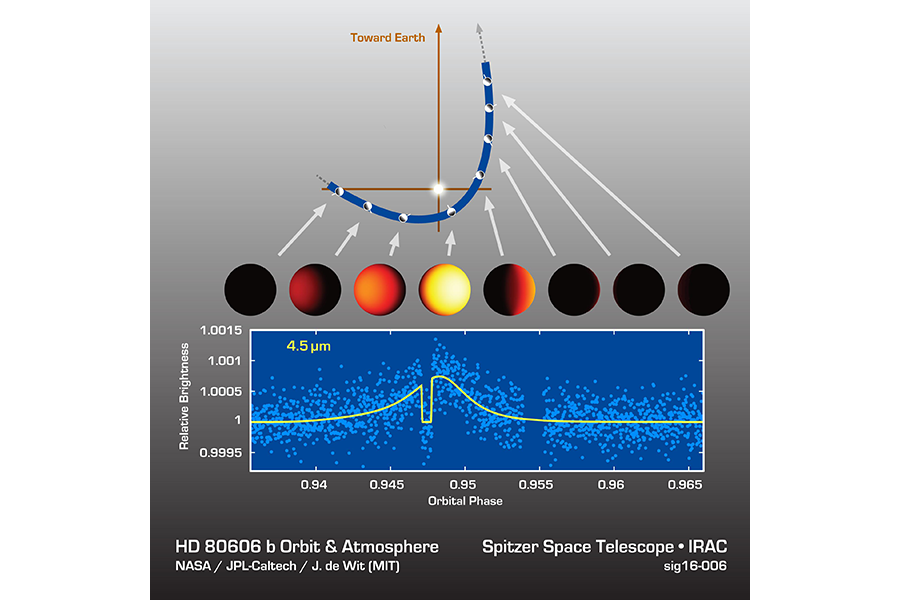

Despite being remarkably normal, scientists have only been able to theorize about how hot Jupiters form. But one particularly mysterious exoplanet, dubbed HD 80606b, is now helping pin down the details. Researchers have used NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to focus in on the stellar body in a new study published in the Institute of Physics' Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Hot Jupiters are gas giants, like Jupiter, but orbit much closer to their star and are therefore significantly hotter than our own gas giants.

HD 80606b has a highly eccentric orbit, meaning it swings very close to its host star during part of its orbit and very far away during another part – somewhat like a comet.

"This planet is thought to be caught in the act of migrating inward," lead study author Julien de Wit of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said in a press release. "By studying it, we are able to test theories of hot Jupiter formation."

But it turns out the popular migration explanation may not be the best one, as the process seems to be taking longer than it should for HD 80606b to shift into a more circular orbit.

This question of how long it takes is an important one, and a main focus of the new study. "Our theories said it shouldn't take that long because we don't see migrating hot Jupiters very often," Dr. de Wit said.

To test those theories, the researchers had to determine how "squishy" the planet is. This sounds strange, but here's how the explanation goes: A planet transitions into a circular orbit from an eccentric orbit as it dissipates heat. That heat is generated from gravitational energy that a star exerts on the oddly orbiting planet when it swings close. The more "squishy" a planet, the more significant the gravitational effect of the star is on it.

"If you take a Nerf ball and squeeze it a bunch of times really fast, you'll see that it heats up," co-author Greg Laughlin, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, explained in the release. "That's because the Nerf ball is good at transferring that mechanical energy into heat. It's squishy as a result."

And HD 80606b is not that squishy.

"The long time scales we are observing here suggest that a leading migration mechanism may not be as efficient for hot Jupiter formation as once believed," Dr. Laughlin said. So perhaps the competing theories that hot Jupiters form in place nearby their stars or spiral closer along planet-forming disks are better explanations.

Regardless, with many hot Jupiters added to the list of confirmed exoplanets, they're certainly not the misfits they were once thought to be. In fact many solar systems have been spotted with exoplanets, both small and large, orbiting tightly around their stars.

As Laughlin said, "We thought our solar system was normal, but that's not so much the case."