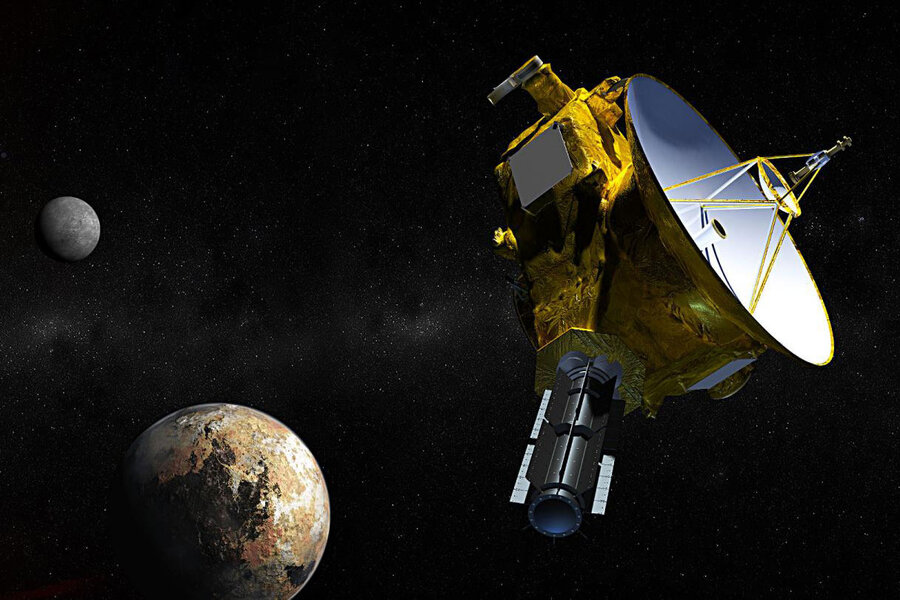

New Horizons data shows Pluto's surface is amazingly diverse

Loading...

Despite its now downgraded status as a “dwarf planet,” the surface of Pluto is turning out to be as varied and complex as any planet. The former ninth planet hosts a wide variety of landscapes that have frequently evolved over millions of years, researchers who studied data from NASA’s New Horizons mission have revealed.

Their results, published in a suit of five studies published Thursday in a special issue of the journal Science, indicate that the icy dwarf planet has been impacted even relatively recently by erosion and cryovolcanoes of ice and methane.

The papers also examined the colors and chemical composition of Pluto and its largest moon Charon, which has been found to contain two primary features – a more “rugged” north and a smoother south, as captured in photos from the mission.

On Pluto, volatile ices, including frozen water and solid nitrogen, are distributed in a complex way, influenced by different seasonal and geological timescales.

Near the planet’s equator and east of the whale-shaped surface feature known as Cthulhu Regio, the researchers found a rich concentration of reddish-brown molecules called tholins.

Other studies looked at Pluto’s atmosphere, which is colder and more compact than the researchers expected, and at Pluto’s four satellite moons: Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. The four moons appeared to rotate quickly, have bright surfaces and are irregularly shaped.

Using a dust counter built by students at the University of Colorado Boulder mounted on the New Horizons space craft, they also found that Pluto continues to modify its environment in space by interacting with the solar wind plasma and energetic particles around it, according to a summary of the papers published by Science.

However, as New Horizons whizzed by Pluto at 31,000 miles per hour last July, the students’ instrument found only a handful of the dust grains that are building blocks of planets.

The space environment around Pluto and its moons contained only about six dust particles per cubic mile, says Fran Bagenal, a CU-Boulder professor who leads NASA’s New Horizons Particles and Plasma team.

“The bottom line is that space is mostly empty,” Dr. Bagenal, who teaches at the university’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), said in a statement. “Any debris created when Pluto’s moons were captured or created during impacts has long since been removed by planetary processes.”

Examining dust grains may seem unusual but studying them can give researchers a much clearer look at how the solar system formed and how it has evolved, including information on the system’s planets, moons, and comets, she adds.

New Horizons, which was launched in 2006, aims to provide scientists with a close look at the icy world at the solar system’s edge, including Pluto and the Kuiper Belt.

The vast belt, which is believed to span more than a billion miles beyond Neptune’s orbit, is believed to contain samples of ancient material that dates to the solar system’s violent formation some 4.5 billion years ago, the statement says.

The presence of dust grains can help the researchers track where they are as they approach the Kuiper Belt, with the instrument picking up thousands of dust grains as it made the nine-year, three-billion mile journey to the icy planet.

“Now we are now starting to see a slow but steady increase in the impact rate of larger particles, possibly indicating that we already have entered the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt,” says Mihaly Horanyi, a professor at the school’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics.

The dust counter, which was built by nearly 20 students, including undergraduates, involves a thin film that sits on a honey combed aluminum structure “the size of a cake pan,” the university’s statement says.

With the device mounted on the spacecraft’s surface, a small electronic box serves as the instrument’s brain and examines each dust particle that hits its detector, allowing students to infer the mass of each one.

There were an additional six instruments mounted on the spacecraft that took other data as the spacecraft made its journey, covering 750,000 miles per day.

Bagenal, who is also a mission scientist for NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter, which launched in 2011, singled out the students’ involvement in the long-running mission.

“CU-Boulder is the only place in the world where students could have built an instrument that eventually flew off to another planet,” she says.