NASA's biggest telescope ever readies for million-mile journey

Loading...

The biggest space mission ever attempted is getting ready for launch.

The James Webb Space Telescope, or Webb, has been built with one goal in mind: to peer into the farthest reaches of the galaxy in order to glean clues about what the universe looked like in its very earliest days. And because Webb has been engineered to be 100 times more sensitive than the Hubble Space Telescope, the granddaddy of all space telescopes, it may even be able to detect signs of life.

“If you put something this powerful into space, who knows what we can find? It’s going to be revolutionary because it’s so powerful,” said Matt Mountain, director of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C., in an interview with Science magazine.

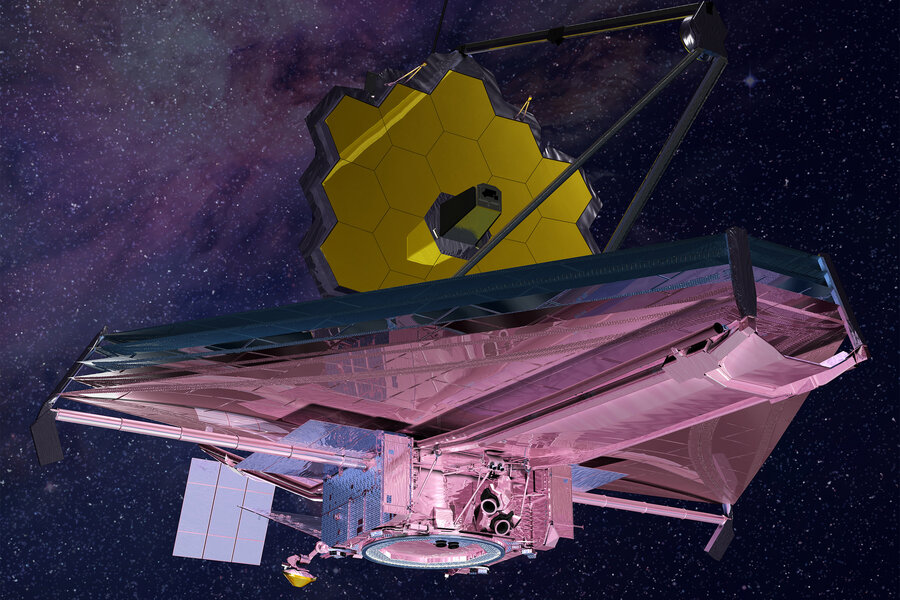

Webb is also unique in its design. It has been engineered to be lighter and more flexible than its famous predecessor. Its mirrors are made of beryllium and coated with gold so that they not only reflect better, but also provide a view of the infrared spectrum. Webb’s instruments have been constructed to work at -382ºF. The sunshield that will protect those intricate instruments is also huge: It’s the size of a tennis court.

Because the telescope is so big, it will be folded up inside the rocket before launching. Once Webb launches in October 2018, the telescope will begin unfolding piece by piece as the mission travels for 30 days and one million miles to its final destination. First, Webb’s instruments that provide power and communication with Earth will emerge. Then, Webb’s giant sunshield will unfurl, and finally, its mirrors will move into position.

That’s the tricky part: Because Webb is traveling so far away, there is currently no rocket capable of ferrying astronauts to fix the telescope if anything goes wrong.

But despite the enormous pressure surrounding the launch preparations, the scientists working on the Webb mission are excited to be a part of this exciting moment.

“It’s just enchanting to be witnessing history,” Marcia Rieke, of the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory in Tucson, told Science.

[Editor's note: This article has been updated to clarify why it would be so difficult to repair Webb if something were to go wrong.]