Farewell Philae: What have we learned from the comet probe?

Loading...

Scientists will no longer attempt to make contact with comet lander Philae, confirmed the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the organization in charge of this mission, on Friday.

Philae was part of the bigger European Space Agency (ESA) Rosetta mission, and the mothership is still orbiting the comet.

While the lander itself may never again be in communication with Earth, it has already taught us much, as well as achieving firsts for mankind, and it paves the way for future exploration.

“It was the first time that a lander and its instruments were landed on a comet and provided data directly measured on a comet’s surface,” says Manuela Braun, of DLR, in an email interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

But conditions on the comet, officially christened 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, have become increasingly hostile, as it veers further from the sun.

Currently 350 million kilometers from our star, Comet 67P is now totally frozen, even during the day, with night temperatures plummeting as low as -180 degrees Celsius (-292 degrees Fahrenheit).

While Philae itself probably remains unfrozen, it is likely covered in dust, and its shaded location means the temperatures will simply be too cold for its systems to function, forcing it into a shivering hibernation.

“Therefore we have been now switching to listening mode only, in case Philae talks again, against all odds,” says Markus Bauer, of ESA, in an email interview with the Monitor.

Yet Philae has already done so much, shattering preconceptions about comets and “capturing the attention of the world.”

“We have learned a lot about comets,” continues Mr. Bauer. “We had to learn for example that the water on comets is not the same water as in Earth's oceans. Our water must therefore have come from other sources.

“We have discovered organic compounds which play a key role in the prebiotic synthesis of amino acids and sugars, which are the ingredients for life.”

And, as Ms. Braun of DLR explains, “We expected a comet’s surface as soft and fluffy – but learned that it could be very heterogenous. The place where Philae finally came to rest has a very hard surface.”

All of these insights will be critical to the planning of future missions.

The Rosetta mission itself will continue for a few more months, with the mothership joining Philae on the comet’s surface in September 2016.

About six years further down the line, the comet will have circled the sun and will bring Rosetta and Philae closer to home once more.

As for those who would follow in Philae’s footsteps, Braun highlights ExoMars, “a mission that will eventually land a rover on Mars drilling up to 2 meters deep into the surface where the chances are the best to find signs of past or present life,” due for launch in mid-March.

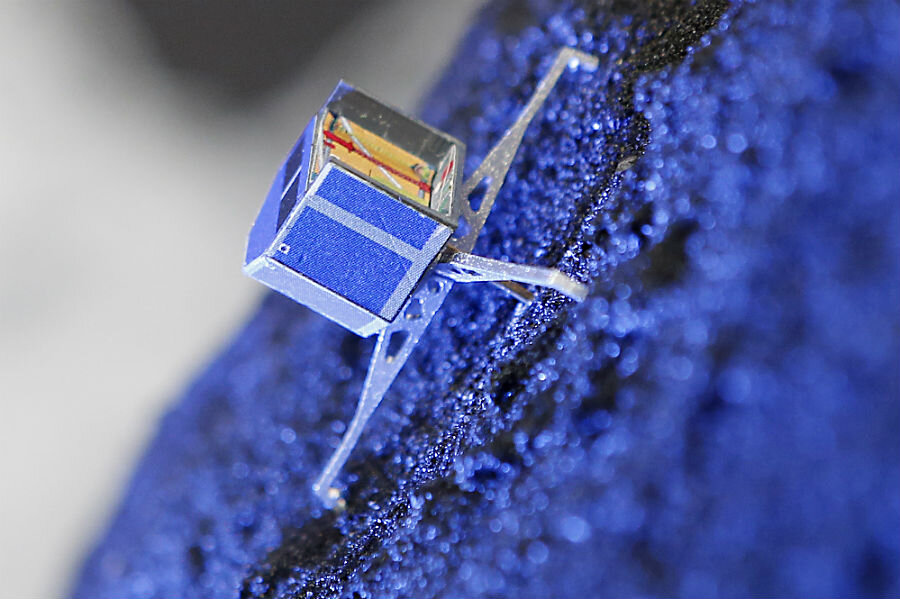

But there is also more asteroid exploration in the works. In fact, just three weeks after Philae launched with Rosetta, another DLR lander shot into space on the back of the Japanese Mission HAYABUSA-2.

This lander, called MASCOT, is hoping to begin its exploration of Asteroid 1999 JU3 in early 2019.