As comet 67P cools, one last-ditch effort to call Philae

Loading...

For half a year now, the European Space Agency’s Philae robot, a washing-machine-size lander that’s been exploring a comet that orbits the sun every 6.5 years between the orbits of Earth and Jupiter, has been silent.

“With every passing day, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is getting further and further away from the Sun, and as such, temperatures are falling on the comet's surface,” the ESA reported Friday on its blog.

This is bad news for Philae – named after an inscribed obelisk found that was instrumental in deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs – because it will not be able to turn on when temperatures reach -60 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Things are getting critical,” says the agency, which is going to make one last attempt to revive Philae by the end of January.

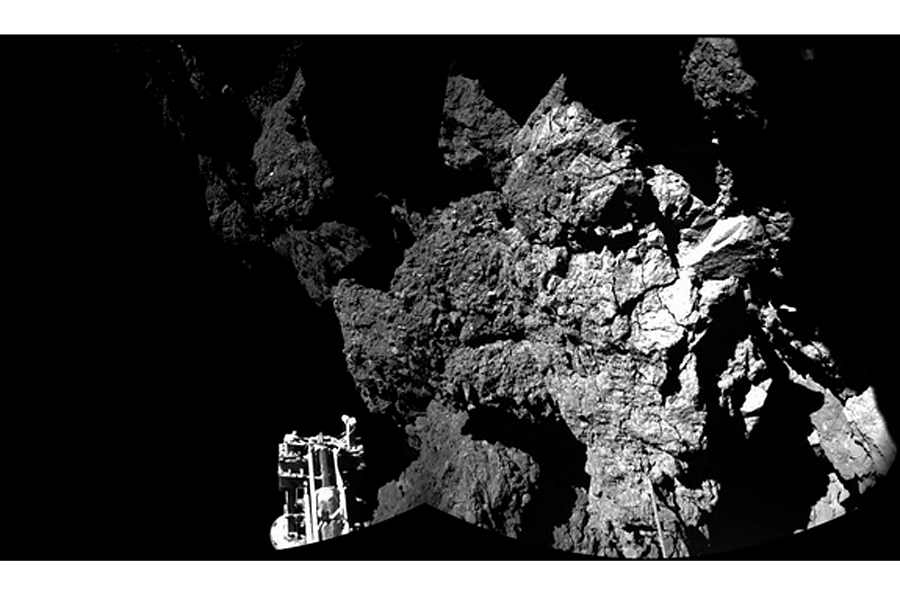

Philae landed on the 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometers) Comet 67P, a dusty snowball shaped like a rubber duck on November 12, 2014. It was the first probe to land on a comet, dropped off there by Rosetta, a spacecraft named after the Rosetta stone, an ancient stele inscribed with three languages that, like the Philae obelisk, provided a key to the modern understanding of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Rosetta traveled for 10 years on its mission to catch a comet and land a probe on it, Space.com reports.

Unfortunately, the landing was far from smooth, as the 220-pound Philae bounced twice off 67P's surface before it touched down in the wrong spot, one that was too shady to charge the explorer’s solar-powered battery.

But it recovered for a couple of days, which it used to gather a wealth of data from the surface of the comet with its 10 instruments. It then transmitted the data to Rosetta, which has been orbiting 67P and relaying data from Philae and from its own studies back to Earth.

"Philae provided us unique information on a comet's surface properties (and interior) that could not be obtained from orbiter measurements alone," Stephan Ulamec, who manages the Rosetta mission from the German Aerospace Center, told Space.com in July, the last time Philae communicated with its team at home.

"We learned so much about comets that now future missions can be adapted in a much better way to this challenging environment," he said.

Among Philae’s discoveries were 16 different organic molecules, including four – methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde, and acetamide – that had never been seen before on or around a comet.

"I think an understanding of the organic compounds that are present in this particular comet will have tremendous ramifications for origin-of-life studies," planetary sciences professor Ian Wright, who’s in charge of one of Rosetta’s instruments, told Space.com.

Astronomers aren’t hopeful about reconnecting with Philae by the end of the month, though the say they will leave the communication unit on Rosetta switched on in case the probe tries to reboot after January.

Otherwise, Rosetta’s mission will end in September 2016 with no final word from Philae.