AI breakthrough: How computers are starting to learn like humans

Loading...

Remember that brainiac kid in class, the one who understood what the teacher was trying to explain after seeing just a few examples on the board?

That is exactly what researchers have been shooting for, as they have developed an algorithm to help computers grasp concepts more quickly and be able to use them more creatively. Researchers from New York University, the University of Toronto and the Massachusetts Institute studied how humans learn quickly with a view toward helping people and machines alike.

"There's all sorts of things that people can do with concepts that computers haven't been able to do," says Brenden Lake, a fellow at New York University and lead author of the study published Friday in Science Magazine. "We wanted to better understand human learning from a computational perspective."

Humans, even children, can see a single example of an alphabet letter, digit, or machine and recognize it immediately. They use prior knowledge to understand a new concept and even sketch or apply the newly seen object to another situation later.

"Before they get to kindergarten, children learn to recognize new concepts from just a single example, and can even imagine new examples they haven't seen," Joshua Tenenbaum, an MIT professor and study author, said in a news release.

Such agile learning has been one of the major gaps between what people do regularly and what the best computers have failed to do, Mr. Lake told the Christian Science Monitor.

"It has been very difficult to build machines that require as little data as humans when learning a new concept," Ruslan Salakhutdinov a computer science professor at the University of Toronto and study author said in a news release.

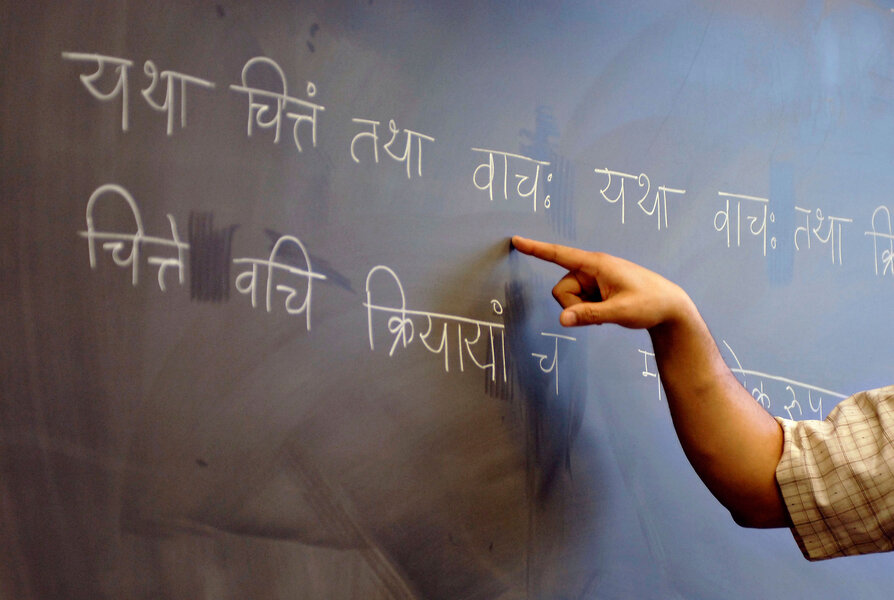

The researchers developed an algorithm to enable a computer to recognize a digit and then recreate it. They 'taught' the computer to recognize letters from 50 different writing systems, including Sanskrit, Tibetan, and Gujarati, according to a news release. Human judges, in comparing newly learned characters drawn by humans and the computer side by side, were hard-pressed to tell the difference.

The key development, Lake says, lies in how quickly the computer mastered the task. Machines have been able to recognize patterns for years – an ATM can 'read' the handwritten numbers on a check and tell what amount of money is being deposited. Those machines, however, processed about 6,000 examples of each individual digit – zero through nine – before they could recognize them as numbers. The new algorithm can recognize a character much more quickly.

"It's less about finding pattern recognition and more about building simple models of the world," Lake says.

The research is a step forward not only for computers, but also in understanding human intelligence, and Lake says he hopes that understanding can eventually help students who need tutoring. It's a holistic approach to artificial intelligence, and the study was released on the same day Tesla's CEO Elon Musk committed a billion dollars to pro-human research on the same topic, Bloomberg reported.

Mr. Musk, who described the development of artificial intelligence as "summoning a demon," told Bloomberg: "If you’re going to summon anything, make sure it’s good."

Musk joined a group of more than 1,000 research who are concerned that artificial intelligence, especially as applied to military uses, could be detrimental to humanity. In an open letter earlier this year, the group wrote:

If any major military power pushes ahead with AI weapon development, a global arms race is virtually inevitable, and the endpoint of this technological trajectory is obvious: autonomous weapons will become the Kalashnikovs of tomorrow. Unlike nuclear weapons, they require no costly or hard-to-obtain raw materials, so they will become ubiquitous and cheap for all significant military powers to mass-produce.... Autonomous weapons are ideal for tasks such as assassinations, destabilizing nations, subduing populations and selectively killing a particular ethnic group.