How Mars may become a ringed planet

Loading...

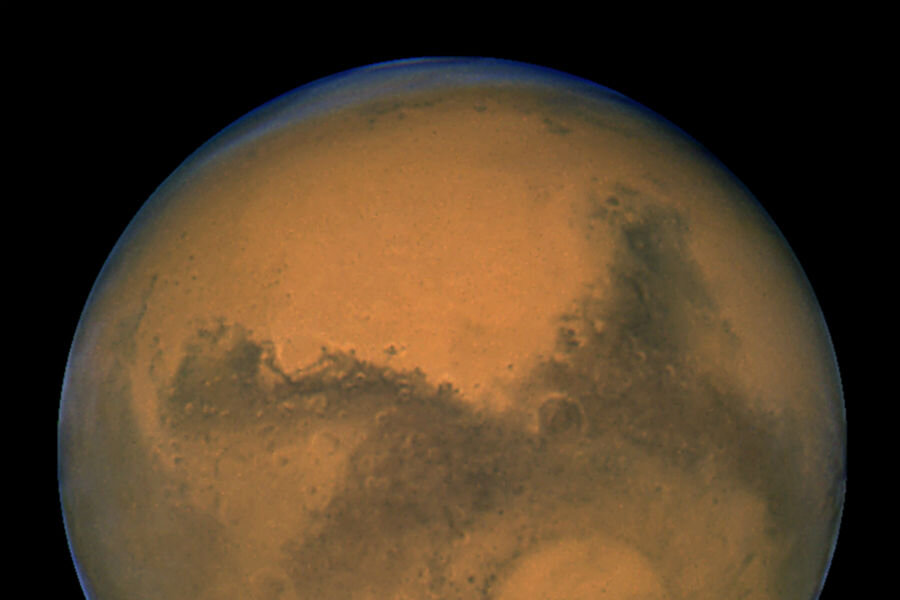

Rings are a common trend in the outer planets of our solar system. The gas giants Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune all have them. And now scientists say rocky Mars might get one, too.

Astronomers have long known that Phobos, the larger of Mars’s two moons, is orbiting ever-closer to the Red Planet, by some seven feet each century. Eventually, either by colliding with the Martian surface or disintegrating under tidal drag from the planet’s gravitational pull, Phobos will disintegrate. Research into the moon's eventual demise, published Tuesday in Nature Geoscience, concludes that Phobos's remains may form a new ring around Mars.

So when will Phobos put a ring on it? Benjamin Black and Tushar Mittal, planetary scientists at UC Berkeley and co-authors of "The demise of Phobos and development of a Martian ring system," predict that it will happen in 20 million to 40 million years.

Dr. Black and Mr. Mittal write that in the earlier days of the solar system ring formation was not uncommon. Saturn’s iconic icy rings for example, come from tidal stripping of "a large, inwardly migrating" piece of satellite space stuff, not all that different from Phobos.

Phobos, called in the paper a "moonlet" because of its relatively small size, is experiencing intensifying tidal pull, according to the researchers, a phenomenon that will cause Phobos to either disintegrate to form a ring, or end in a collision with Mars.

A geologic analysis and some mapping of Phobos led Black and Mittal to conclude that Phobos is composed of loose, “heavily damaged” materials, meaning the ring will not persist for very long, about 106 to 108 years, before dispersing or falling from Mars’s orbit and back to the surface.

Mars is much changed since it became a planet a few billion years ago. The Red Planet began watery and warm, but the sun long ago stripped its atmosphere, leaving it the uninhabitable planet we know today. With Phobos' decline, we can now foresee a time when the planet will transform again.

By observing the evolution of Phobos and predicting its demise, Black and Mittal write that scientists might learn how moons played a role in creating the present-day solar system. They suggest that a NASA Discovery mission, which sends relatively low-cost spacecraft to observe the solar system and beam back data, might help to better understand the composition and fortitude of Phobos, and allow them to test their conclusion.

A Discovery mission would be Earth's final chance: Phobos is the last of what were once numerous inwardly-orbiting satellites of our solar system.