Smog on Mars? How acidic fog melted Martian rocks

Loading...

Scientists may have solved one of Mars's biggest riddles.

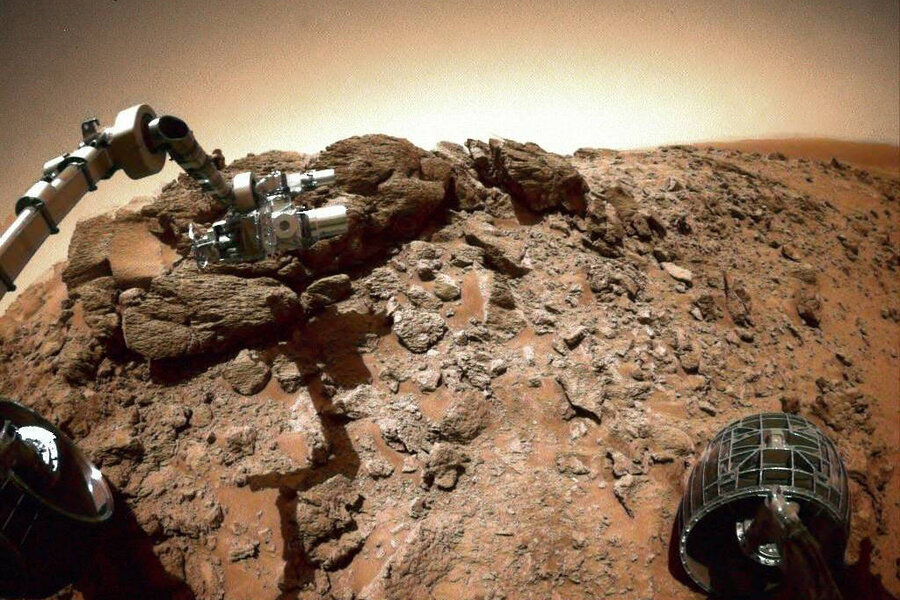

For years, the lumpy appearance of rocks in a 100-acre section of outcrops in Gusev Crater have stumped Mars scientists. Most of the instruments on the Spirit rover noted something different about these agglomerations, but, puzzlingly, spectrometer tests showed that they had the same chemical structure as non-lumpy rocks nearby.

"That makes us think that they were made of the same stuff when they started out," explains Ithaca College planetary scientist Shoshanna Cole. "Then something happened to make them different from each other."

After poring over data beamed back to Earth by NASA's rovers, Professor Cole developed a theory to explain that "something": acidic vapors from volcanic explosions had dissolved some minerals into a gel-like substance, which then hardened into the patterns seen today, she told colleagues on Monday at the Geological Society of America's annual conference.

For evidence, she points to the rocks' range of iron oxidation states, which were surprisingly varied across the relatively small Cumberland Ridge, suggesting that something had chemically reacted with the rocks to different degrees.

Geological scientist Ralph Milliken, an assistant professor at Brown University who was not involved in the study, said the new theory is consistent with earlier models.

"What I really like about Shoshanna's work is that it's a nice integration of all the instruments," he told Discovery. "It's exactly what a geologist would do today if they went out in the field."

Cole gives credit to the rovers.

"Spirit's the rover who always had to try harder," she said in remarks published by the GSA. "She was sent to Gusev Crater to look for lake deposits, but landed in lava field. She had to make a long trek to the Columbia Hills to find evidence of ancient watery environments."

In the 1980s, as Americans worried about the effects of acid rain, attention turned to California, which proved to have an acid fog problem, too: acid readings 100 times as high as those caused by acid rain.

Although it's thought to have contributed to an uptick of deaths in London in the mid-twentieth century, researcher Michael Hoffmann reassured Californians that they didn't need to worry. Unlike in the United Kingdom, California's acidic fog tended to move on quickly, before it could do much damage.

Volcanic smog, or "vog," occurs here on Earth as well, and many Hawaiians have become accustomed to the air pollutant.

If anyone's complaining about vog on Mars, though, scientists haven't found them yet.