Hubble's spectacular Jupiter portrait: What happened to the Great Red Spot?

Loading...

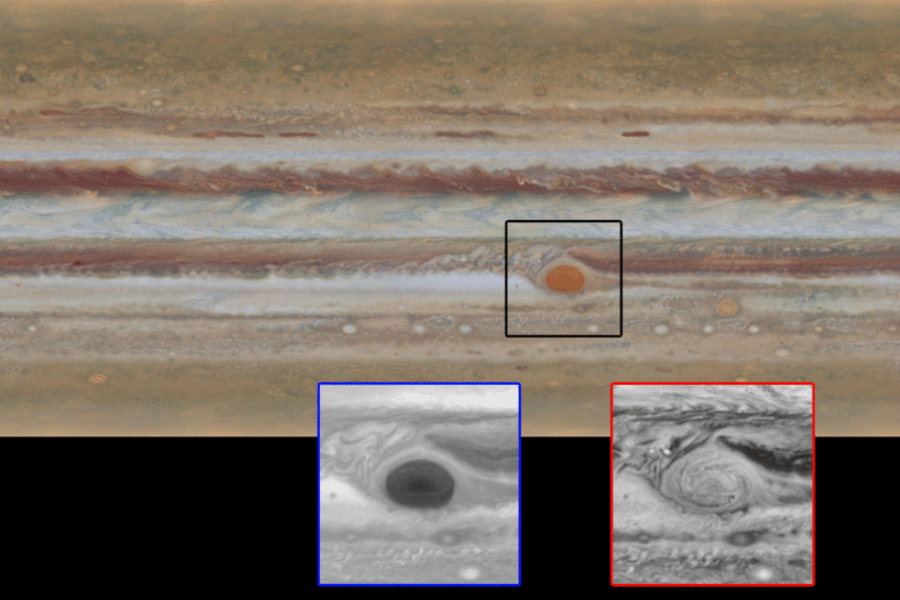

Every year, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope snaps photos of the solar system's outer planets. This year, the "people's telescope" has turned in images of Jupiter with a rarely seen wave just north of the planet's equator, as well as a surprising feature at the center of the planet's Great Red Spot.

“Every time we look at Jupiter, we get tantalizing hints that something really exciting is going on,” said Amy Simon, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland in a statement. “This time is no exception.”

The annual photo shoot helps contemporary and future researchers observe changes over time on the giant planets spinning far from the sun. Hubble's captures help update maps and include characteristics like winds, clouds, storms, and atmospheric chemistry, according to the space agency.

The Great Red Spot, a major anticyclonic storm (meaning the winds turn counterclockwise, even though its in the planet's southern hemisphere), continues to shrink and become more circular, as has been observed for years. Its name is also becoming less true, as the storm weakens the spot is appearing more orange. The long axis of the storm is about 150 miles shorter now than it was in 2014, according to NASA, which adds that the storm had been shrinking at a faster rate than usual.

NASA also reports seeing a unique "wispy filament" that crosses the width of the storm's vortex, and moves with winds that can exceed 330 miles per hour.

The other curiosity is in Jupiter’s North Equatorial Belt, where researchers spotted a mysterious wave that had been observed on the planet just once before, decades ago. In those images, taken by Voyager 2, "the wave is barely visible," according to NASA, until with this latest set of images, where a wave can be seen in a region of cyclones and anticyclones. Baroclinic waves, which are similar, can occasionally be seen in Earth’s atmosphere where cyclones are forming.

“Until now, we thought the wave seen by Voyager 2 might have been a fluke,” said co-author Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “As it turns out, it’s just rare!”

Hubble will also take researchers to Neptune and Uranus, and maps of those planets will also be created and put in the public archive, as part of NASA's Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy program.

Co-author Michael H. Wong of the University of California, Berkeley underscored the value of the program in a statement, saying the maps scientists create year over year are not just to further understand our distant neighbors, "but also the atmospheres of planets being discovered around other stars, and Earth’s atmosphere and oceans, too.”