How the spider got his knees

Loading...

Spider torsos seem to hang off their eight legs, with their eight knees poking up above the rest of their bodies.

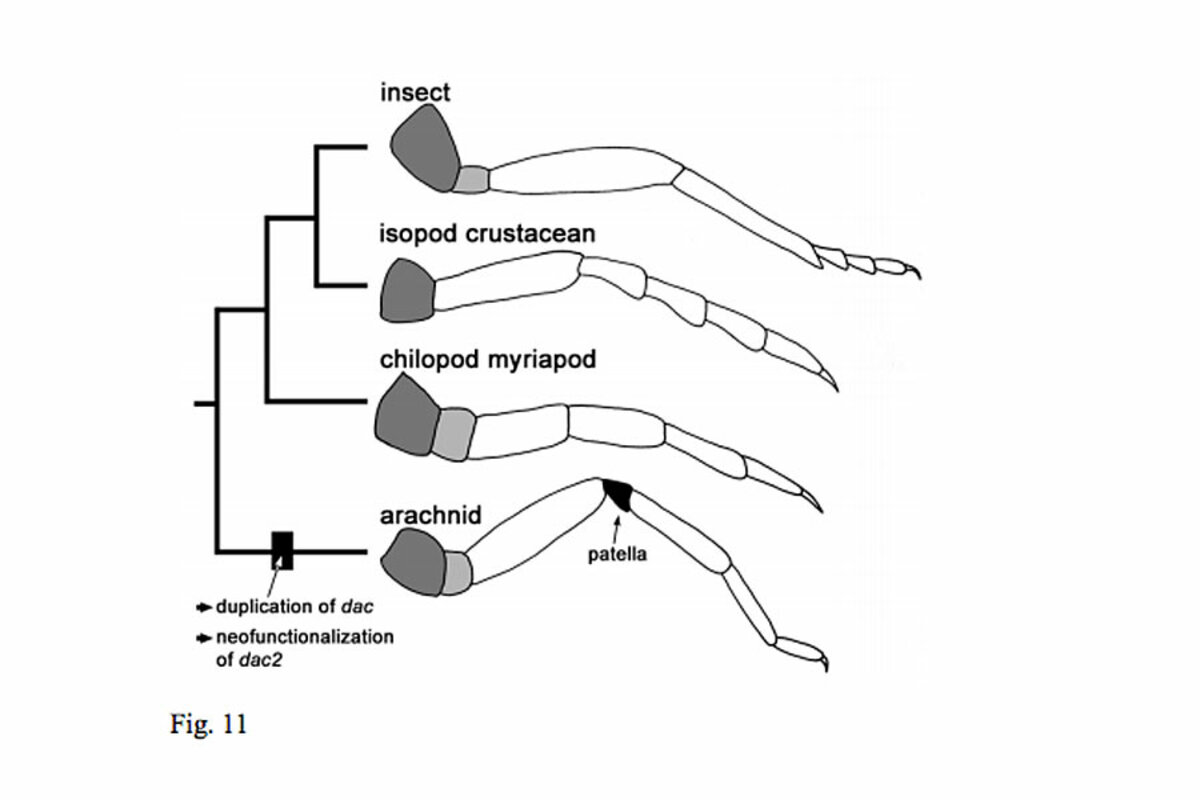

Arachnids have seven different leg segments, giving them a distinctive walk, but it’s those high knees that set them apart from their fellow arthropods, like lobsters, centipedes, and crayfish.

Those all have multi-segmented legs, but none have the knee segment – the patella.

How did spiders get this unique feature? Genetic duplication, say researchers.

A gene involved in leg development, first identified in fruit flies, shows up twice in the spiders studied for a paper in Tuesday's issue of "Molecular Biology and Evolution." This second gene created the patella.

The authors outlined three possible scenarios that could result from gene duplication, if the second gene isn’t lost. In one, the double genes support functionality of the feature they produce. Another sees the second gene taking over an aspect of the original gene’s job, becoming more specialized. But it’s the third, called neofunctionalization, that produced spider knees.

In neofunctionalization, the duplicate gene finds a new function, which then becomes part of the essential functions of the organism.

"Species constantly adapt and evolve by inventing new body features," said study author Nikola-Michael Prpic in a news release. "Our work shows how a gene can be duplicated and then used during evolution to invent a new morphological feature."

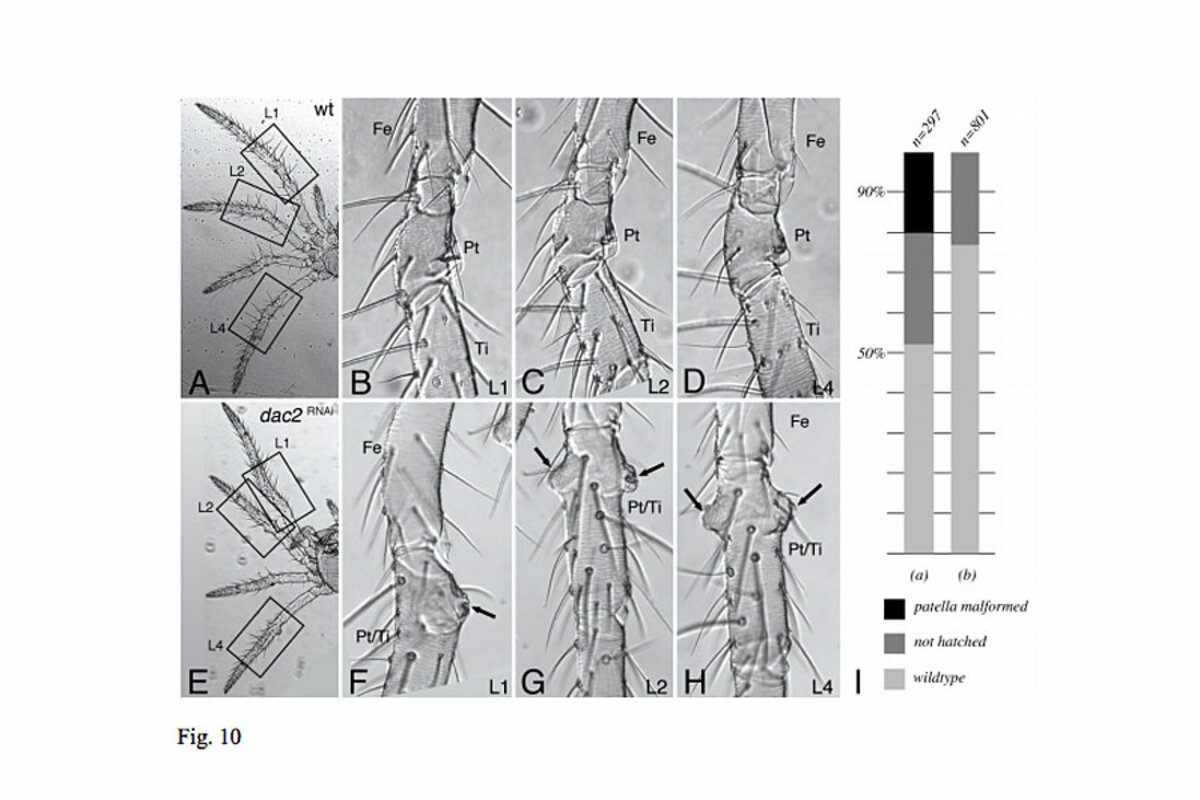

The researchers used RNA interference experiments to test if this duplicated gene, dachshund, created the patella in arachnids. When the scientists deactivated dac2, the second dachshund gene, the patella and tibia fuse, forming a single leg segment.

The researchers performed this test on the common house spider, Parasteatoda tepidariorum, and the cellar or skull spider, Pholcus phalangioides.

The spiders are only distantly related, but both displayed the same results: the patella and tibia fused if dac2 was turned off. Thus, spiders evolved knees before the lineages split, say the authors.