Did our tooth enamel evolve from scales?

Loading...

| Washington

The origins of the enamel that gives our teeth their bite is no ordinary fish tale.

Scientists said on Wednesday fossil and genetic evidence indicates enamel did not originate in the teeth but in the scales of ancient fish that lived more than 400 million years ago, and only later became a key component in teeth.

Enamel is the hardest tissue produced in the bodies of people and other vertebrates but scientists have been uncertain about its beginnings.

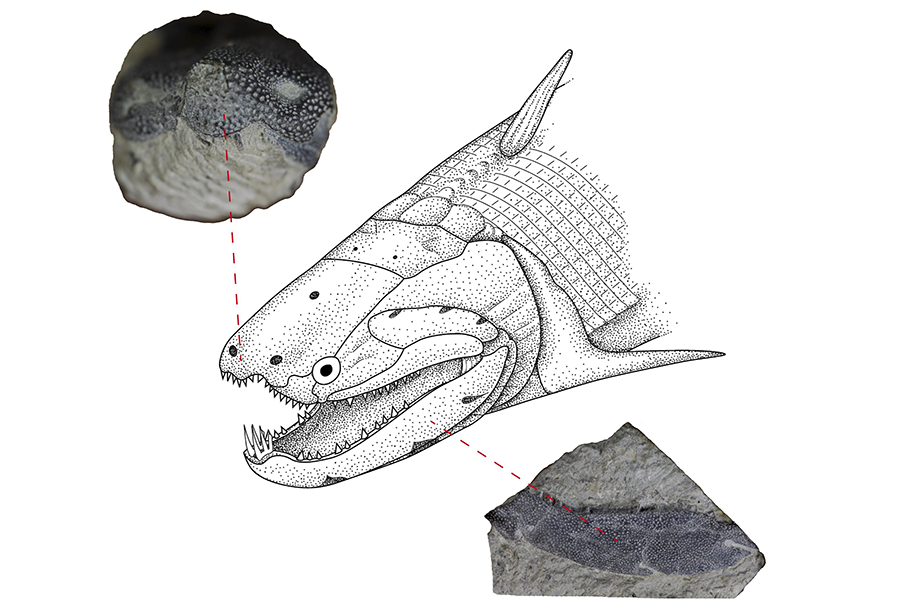

The researchers examined fossils of two primitive bony fish from the Silurian Period, a time of evolutionary advances in marine life, and found an enamel coating on their scales but no enamel on their teeth. Only millions of years later through evolutionary processes did fish exploit the enamel to make teeth harder and stronger, they said.

"This is important because it is unexpected. In us, enamel is only found on teeth, and it is very important for their function, so it is natural to assume that it evolved there," said paleontologist Per Erik Ahlberg of Sweden's University of Uppsala, whose research appears in the journal Nature.

"As the wolf in 'Little Red Riding Hood' said: 'All the better to eat you up with!' They are hugely important as food-processing structures."

Enamel, shiny and white, is one of the main tissues in teeth in most vertebrates, composed almost entirely of calcium phosphate.

Fish are the ancestors of terrestrial vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, including humans.

"Although this tissue on our teeth is used for biting or shearing, it was originally used as a protective tissue such as in living primitive fishes including gars and bichirs," added paleontologist Qingming Qu of Uppsala University and the University of Ottawa.

Fossils showed a fish called Andreolepis that lived 425 million years ago in Sweden had a thin enamel layer on its scales. Another called Psarolepis, from 418 million years ago in China, had enamel on its scales and also the bones of the face. Neither had tooth enamel.

The genome of the spotted gar, a freshwater fish from the central and southern United States largely unchanged since the age of dinosaurs, provided more clues.

Gar scales, like those of Andreolepis and Psarolepis, are covered by a shiny enamel-like substance. The researchers pinpointed genes relating to enamel formation that were active in the gar's skin, showing that this substance really is a kind of enamel.

(Editing by Eric Walsh)