Proposed NASA mission to Saturn moon: If there's life, we'll find it

Loading...

"If Enceladus has life, we will find it."

It's a brash boast regarding Saturn's small, ice-covered moon, but a team of scientists has backed it up by asking the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the money to build a small orbiter designed to sample the moon's geyser-like plumes for evidence of habitability and perhaps life.

NASA is expected to announce its decision in early October. As the researchers await the agency's decision, they have been heartened by confirmation that Enceladus hosts a global ocean beneath its icy crust.

Announced Tuesday, the confirmation puts to rest the alternative: that the plumes' source is large pocket of liquid water limited to the moon's south polar region.

The difference between a regional sea – with the capacity of Antarctica's Lake Vostok – and a global ocean is more than academic.

Both could be hospitable to life under the right conditions, says Steven Vance, an astrobiologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. But "a global ocean is much more compelling."

It allows researchers to entertain the possibility that Enceladus' ocean could host a diverse, vigorous ecology, supported by global ocean circulation patterns, Dr. Vance says.

The very presence of a global ocean "says maybe it's been there for a long time," he adds. "If you want to know whether there might be complex life in some extraterrestrial ocean, you want to know if the ocean's been there for a long period of time."

Overnight, Enceladus has become a more accurate, if smaller, analogue to Jupiter's moon Europa, which also shows evidence of hosting an under-ice, global ocean. In June, NASA announced it would begin development work on a spacecraft to visit Europa, to be launched in the 2020s. The insights that researchers gain at Enceladus about icy moons with global oceans could help with planning for the mission to Europa, Vance says.

The new analysis, published online Tuesday in the journal Icarus, "makes clear how important Enceladus is," writes Jonathan Lunine, a planetary scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., who heads the team proposing the Enceladus Life Finder (ELF) mission, in an e-mail. "I’m keeping my fingers crossed."

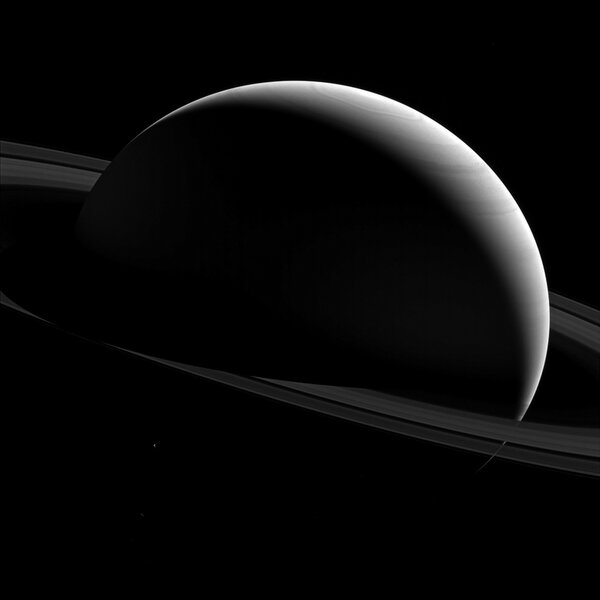

Scientists discovered the plumes in 2005, during the initial stage of NASA and the European Space Agency's Cassini-Huygens mission to the Saturn system. Since then, evidence has mounted that the plumes, which resupply Saturn's E-ring with fresh material, originate from a layer of water perhaps six miles thick. This ocean lies beneath a shell of ice between 19 and 25 miles thick and sits atop a rocky core. The plumes escape from a series of fissures in the ice, dubbed tiger stripes, near the moon's south pole.

Evidence also has mounted that the large, rocky core is porous, allowing water to flow through it to pick up heat. This would reinforce an idea that at least in the south polar region, where the icy tiger stripes exhibit more warmth than the surrounding surface, a hydrothermal field may lie beneath the ocean.

Indeed, the porous core could mean that Enceladus "is one big hydrothermal system," says Vance, who is familiar with the new study as well as the proposal of Dr. Lunine's team.

It is into the plumes that Lunine and colleagues hope to send their ELF. It is one of several Discovery Program proposals that NASA is sorting through in selecting one for launch around 2021.

Cassini already has laid the groundwork, uncovering sodium and potassium in the plumes, in addition to water, methane, and simple and complex organic molecules, as well as oxygen and nitrogen. Tiny silica grains that the craft may have detected would point to water in contact with rock at high temperatures.

Energy, a salty ocean, and organics render the presence of life plausible, the team holds.

ELF would build on this, carrying spectrometers far more capable than those on Cassini. One spectrometer would analyze gases in the plumes. The other would gather and analyze dust grains.

The instruments would determine how habitable the ocean truly is – its temperature, how acidic or alkaline it might be (initial evidence suggests alkalinity comparable to household ammonia), and how much chemical energy is available to support life, for example.

They also would look for patterns in the mix of amino acids that appear significantly different from those formed through nonbiological processes, hunt for clustering among molecules known to build membranes, and look for isotopic signals that life might be present.

The team envisions eight to 10 flybys: the first four to meet the basic science goals; four more to zero in on intriguing initial observations or to erase ambiguity in the early results; and two additional orbits for contingencies.

[Editor's note: This story was updated on Sept. 17.]