Where did monogamy come from? Could we owe it all to ... grandmas?

Loading...

If your grandmother keeps urging you to settle down with a romantic partner, you aren't alone. It turns out grandmothers may have been promoting monogamy and the nuclear family unit since the beginning of human civilization.

According to the "grandmother hypothesis," first suggested by University of Utah anthropologists Kristen Hawkes, the role of grandmothers as a secondary caretakers played a major role in allowing young women to have more children and ultimately live longer.

“The grandmother’s importance in helping to raise families led to an evolutionary preference for women who could live longer, and thus look after grandchildren longer,” as Tony Booth explains in The Market Business. “As a result longevity genes became more prominent in the human population and in time increased the lifespan of all humans.”

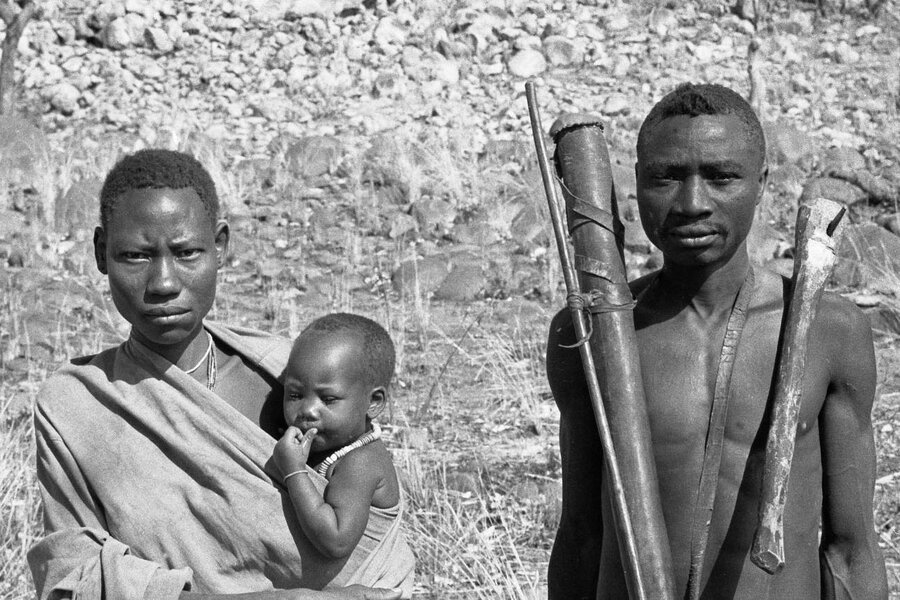

In a new study published online in the Sept. 8 edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, senior author Ms. Hawkes conducted research studying both chimpanzee populations and hunter-gather human populations in Africa. While chimps have no special pairing relationships, “pair bonds are universal in human societies and distinguish us from our closest living relatives,” Hawkes and her colleagues write.

“Our hypothesis is that human pair bonds evolved with increasing payoffs for mate guarding, which resulted from the evolution of our grandmothering life history,” the study states, contradicting the commonly expected view that pair bonding “resulted from male hunters feeding females and their offspring in exchange for paternity of those kids so the males have descendants and pass on genes,” Hawkes says in a University of Utah press release.

By studying the differences between chimpanzees and humans, it’s become apparent that a grandmother culture may be the reason humans tend to find a long-term partner rather than find several mates like chimpanzees do, according to the Hawkes.

Most mammal species have more fertile females than fertile males, which lessens the chance that males will exhibit mate-guarding. However, as human lifespan lengthened via grandmothering, older men remained fertile while women’s fertility plateaued at about age 45. The scarcity of fertile females could explain why human relationships adapted, the study suggests, making it more “advantageous for males to guard a female and to develop a pair bond with her.”

“This male bias in sex ratio in the mating ages makes mate-guarding a better strategy for males than trying to seek an additional mate, because there are too many other guys in the competition,” Hawkes says. “The more males there are, the more their average reproductive success goes down.”

Not all are convinced of Hawkes theories however, citing that increasing average lifespans are attributed “largely to huge reductions in infant and child mortality due to clean water, sewer systems and other public health measures” or that “increasing brain size in our ape-like ancestors was the major factor in humans developing lifespans different from apes,” as the UofU release explains.