Rosetta spacecraft spies dynamic sinkholes on a comet

Loading...

According to new research, comets are more than aimless clumps of icy rock – in fact, they lead quite dynamic lives.

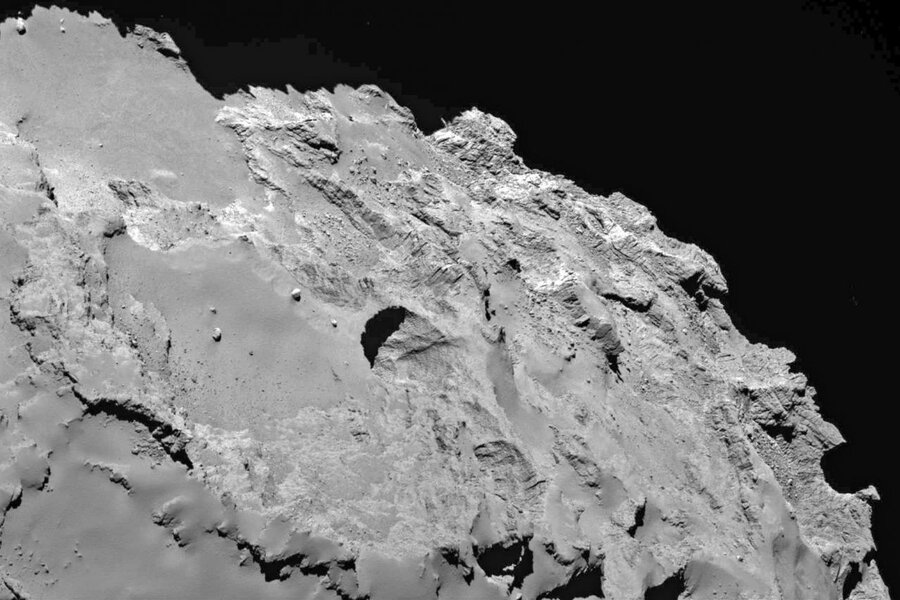

When the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft began orbiting the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko last summer, astronomers were fascinated by deep-set, circular gaps on the comet’s surface. A study published Wednesday in Nature proposes that those pits are actually giant sinkholes. These new findings suggest that comets undergo significant anatomical changes as they approach central stars, such as our Sun.

Rosetta was first launched by the ESA in 2004. After a 10-year journey, the craft came upon comet 67P, capturing some surprising data in the process. The comet’s face featured several near-perfectly circular pits, ranging from 10 to several hundred meters across.

"These strange, circular pits are just as deep as they are wide. Rosetta can peer right into them," said the study's co-author Dennis Bodewits in a press release.

Shallow pits have been observed on other comets, but the depths recorded on 67P were unusual. Researchers initially blamed the holes on explosive events, like the one Rosetta observed upon reaching the comet, but found that even large explosions could only leave craters a few meters in diameter.

It turns out the answer was right here on the Earth. Dr. Bodewits and colleagues believe sinkholes formed on the comet just as they do on our planet – by a process called sublimation. Under heat and pressure, some solid compounds sublimate, skipping the liquid phase and going straight to the gaseous phase. In comets, an internal heat source can sublimate underground ice. As the solid ice gives way to gas, the surface collapses in on itself, leaving a gaping sinkhole.

"Now, for the first time, we have a clear link between jets and between these pits that we have observed on the surface," co-author Jean-Baptiste Vincent, a planetary scientist at the Max Planck Institute, told Space.com.

"We think it's a common process. It's happening on all comets – maybe on slightly different timescales, but we think it's happening everywhere," Mr. Vincent added.

Last week, the Rosetta mission was extended by nine months. This will give researchers the opportunity to study 67P not only during, but after it reaches perihelion – the point in the comet’s orbit when it is closest to the Sun. At the end of Rosetta’s last nine months, ESA hopes to organize a comet landing, thereby adding to a growing list of insights obtained over the course of the mission.