What future ‘eyes’ in space will see

Loading...

| Baltimore

Hubble may still be in its prime, but that hasn’t prevented astronomers from contemplating an enormous successor: an observatory dubbed the High Definition Space Telescope (HDST).

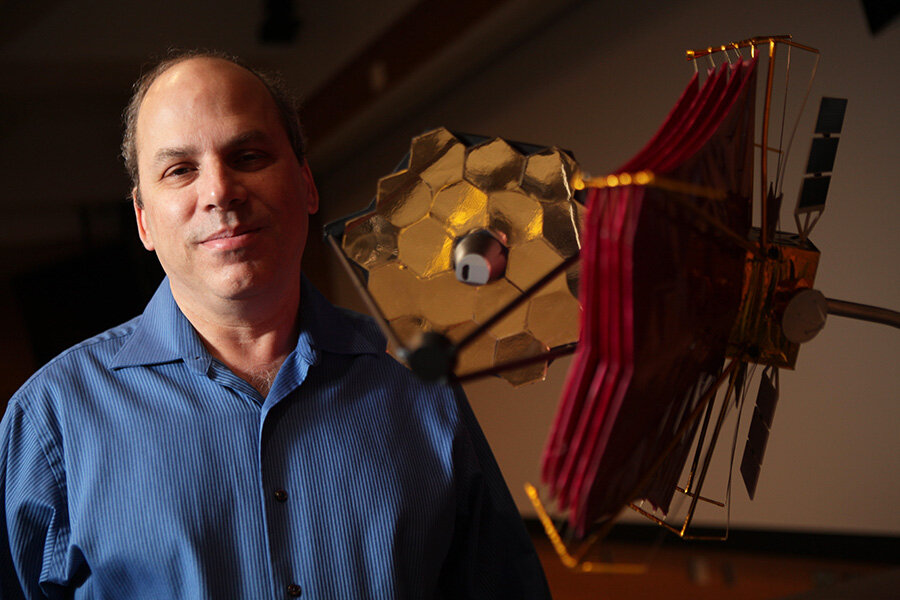

With a mirror from 8 to 16 meters across (Hubble’s is 2.4 meters across and the James Webb Space Telescope’s is 6.5 meters), the telescope would be as much as 2,000 times as sensitive to faint objects as Hubble. And it would provide remarkably detailed data, says Marc Postman, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute and a member of a group assessing the technology needs for such an observatory.

The telescope would allow astronomers to pick out individual sunlike stars in galaxies as far as 30 million light-years away, he says. On grander scales, the telescope would be able to identify features as far away as 326 light-years anywhere across the universe.

Astronomers have been exploring concepts for telescopes like this since the late 1980s. But Hubble has about a decade of operation left at best, and lead times on such projects are long. Technological advances and compelling scientific questions raised during the Hubble era are driving the interest.

The study group, convened by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy and chaired by University of Washington astronomer Julianne Dalcanton and Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sara Seager, is expected to release its findings in June.

A 10-meter-class space telescope covering light from near-infrared through ultraviolet, as Hubble does, would revolutionize efforts to identify the potentially habitable – or potentially already inhabited – rocky planets of sunlike stars, Dr. Postman notes.

Parked in an orbit nearly a million miles from Earth, HDST would be able to spot such planets out to distances of about 146 light-years.

In just a week’s worth of observation, HDST could gather enough spectral information from a planet’s atmosphere to detect molecular oxygen, methane, and water vapor; gauge the atmosphere’s thickness; spot a protective ozone layer; or even pick out indirect signs of vegetation.

The James Webb Space Telescope will conduct similar observations, but likely for just a handful of larger planets orbiting dimmer, cooler stars; the HDST in principle could observe as many as 50 systems.

The HDST also would be a boon to cosmologists. It would allow more-detailed observations of processes affecting the evolution of galaxies and their populations of stars and provide fresh insights on dark matter and dark energy.

The panel foresees HDST working in tandem with a new generation of large ground-based telescopes and other space-based observatories, as Hubble does. It would also require major contributions – perhaps telescope hardware – from international partners.