How lasers could be the future of space cleanup

Loading...

Lasers may be the future of garbage disposal – in space, at least.

In a paper published in the latest issue of Acta Astronautica, researchers at the Riken research institute in Tokyo proposed a way to end the growing problem of space debris by shooting them down with lasers.

The method would track space debris using the Extreme Universe Space Observatory’s (EUSO) super-wide-field telescope, mounted on the International Space Station. The telescope, which is based aboard the space station's Japanese Experiment Module, was designed to detect high-energy cosmic rays.

The study proposes using EUSO to spot the debris and then shooting them with powerful laser pulses from a high-efficiency fiber laser, also aboard the space station. The pulses would knock objects into the Earth’s atmosphere, where they would burn up.

This method, which uses lightweight and flexible optical fibers as a medium for the laser pulses, could find and deorbit even the smallest space debris, according to the researchers’ statement, released Friday.

“Our proposal is radically different from the more conventional approach that is ground based, and we believe it is a more manageable approach that will be accurate, fast, and cheap,” Toshikazu Ebisuzaki, chief scientist at Riken’s Computational Astrophysics Laboratory and head of the space debris research team, said.

“We may finally have a way to stop the headache of rapidly growing space debris that endangers space activities,” he added.

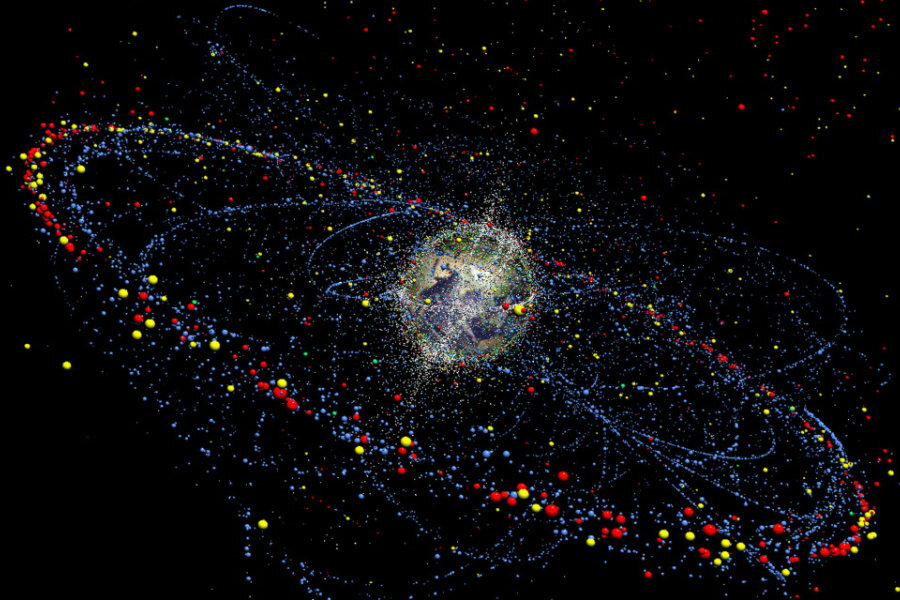

Space debris, also known as space junk, refers to the collection of non-functional manmade detritus – old satellites, rocket stages, and broken fragments – that orbit the Earth or re-enter the atmosphere. As of last year, NASA estimated that more than 500,000 pieces of debris the size of a marble or larger are orbiting the Earth.

Many of these objects are orbiting the Earth at about 17,500 miles per hour, posing a danger to all spacecraft, especially to those with humans aboard.

Worse, existing debris colliding with one another generates more debris, which would also collide with one another, creating even more litter. This effect, called the Kessler Syndrome, after the NASA scientist who first described it in 1978, could form a self-sustaining cloud of colliding fragments and objects that would not only be catastrophic for satellites but also potentially deadly for astronauts – think Alfonso Cuarón’s film “Gravity.”

Total disaster hasn’t happened yet, but enough collisions have occurred to prove that space junk can have consequences: In 2007, for instance, China's military destroyed one of their own weather satellites during an anti-satellite missile test, creating several hundred thousand debris fragments. The amount of space junk orbiting the Earth has only increased since.

"There is a wide and strong expert consensus on the pressing need to act now to begin debris removal activities," Heiner Klinkrad, head of the European Space Agency's Space Debris Office, said in a statement at the 2013 European Conference on Space Debris in Germany. "Our understanding of the growing space debris problem can be compared with our understanding of the need to address Earth’s changing climate some 20 years ago."

Scientists and companies around the world have proposed everything to remove the debris, from nets and robotic arms to solar sails and slingshots.

For their part, the Riken researchers plan to conduct an experiment aboard the ISS using a miniature version of the EUSO’s telescope and a laser with 100 fibers to prove their concept’s feasibility.

“If that goes well, we plan to install a full-scale version on the ISS, incorporating a three-meter telescope and a laser with 10,000 fibers, giving it the ability to deorbit debris with a range of approximately 100 kilometers,” Dr. Ebisuzaki said. “Looking further to the future, we could create a free-flyer mission and put it into a polar orbit at an altitude near 800 kilometers, where the greatest concentration of debris is found.”