How Jupiter may have destroyed the inner solar system

Loading...

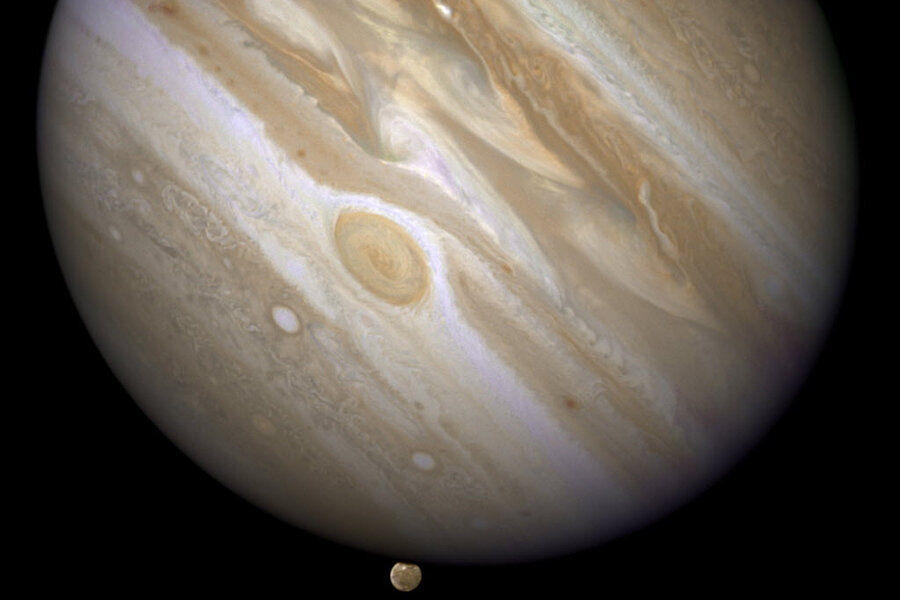

In the early days of our solar system, a rogue Jupiter destroyed everything in its path.

And according to researchers, Earth owes its very existence to those collisions.

Caltech astrophysicist Konstantin Batygin and UCSC’s Greg Laughlin conducted statistical studies based on Jupiter’s wandering orbit, in hopes of zeroing in on what makes our solar system so apparently unique. Their findings were published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Exoplanetary searches, like NASA’s Kepler Mission, suggest a “default” mode of planet formation. In this model, systems that develop around Sun-like stars tend to produce at least one massive, close-orbiting planet.

“The innermost realm of our own solar system, by contrast, is completely, mysteriously empty,” Dr. Laughlin said. “So it was the context provided by the extrasolar planets that gave us a clue that something is unusual in our own.”

Until fairly recently, there was no explanation for how those planets could have gone missing. In 2012, researchers first described an interplanetary model based on the suggestion that Jupiter’s orbit is not fixed – that it migrated nearer to the sun during the formation of our solar system, only to turn and pull away over millions of years. Because it seemed to resemble a sailboat “tacking” around a buoy, researchers dubbed it the “Grand Tack Hypothesis.”

As Jupiter ducked into close orbit, gravitational disturbances would have whipped inner planets into each other. Then, “headwinds” of swirling gas would have propelled remaining debris into the Sun. Jupiter would have remained, for the time being, in close orbit with its central star.

Typically, that’s where the story ends. The formation of giant planets is unusual, so two would be considered a rarity. But Jupiter was drawn away by another massive celestial body – Saturn. As the space between Jupiter and the Sun widened, new planets were able to develop out of leftover materials from the collisions. This theory is supported by evidence that our inner-to-middle planets – Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars – are younger than our outer planets. They are also rocky, rather than gaseous, and their atmospheres are comparatively thin.

“Over the years, we had looked at a number of approaches for clearing out the inner solar system,” Laughlin said, “and none of them were particularly promising. But then Konstantin pointed out the idea of a collisional cascade, and it became, as far as we could tell, very straightforward to understand what might have happened. It was surprising that the Grand Tack, which has been getting a fair amount of attention over the past few years, works so well in explaining why our inner solar system has ‘gone missing’.”

Laughlin’s statistics and simulations are based on the Grand Tack Hypothesis – as such, his findings can only be as accurate as that model. But luckily, there are ways to test them.

“Our theory predicts that there should be an anti-correlation between the presence of super-Earth planets with short orbital periods, and the presence of a giant planet with an orbital period of roughly a year or more,” Laughlin said. “The validity of this anti-correlation should be testable with NASA's TESS Mission, currently planned for launch in 2017.”

And if Grand Tack proves true, it could have serious implications for humanity’s ongoing search for exo-Earths. Laughlin’s findings suggest that planets with Earth-like masses and orbits should have “substantial” atmospheres – thick with hydrogen, helium, water vapor, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen.

“In the context of our hypothesis, Earth-mass planets should be very common,” Laughlin said. “Truly Earth-like planets, however, with solid surfaces and atmospheric pressures similar to what we have here on Earth, would be expected to be rather rare.”

“I would hazard a guess that the Earth will indeed turn out to be rather special,” he added. “It will be very interesting to see how this hypothesis holds up over the coming years and decades as we learn more about extrasolar planets.”