Did comet dust light up the Martian sky?

Loading...

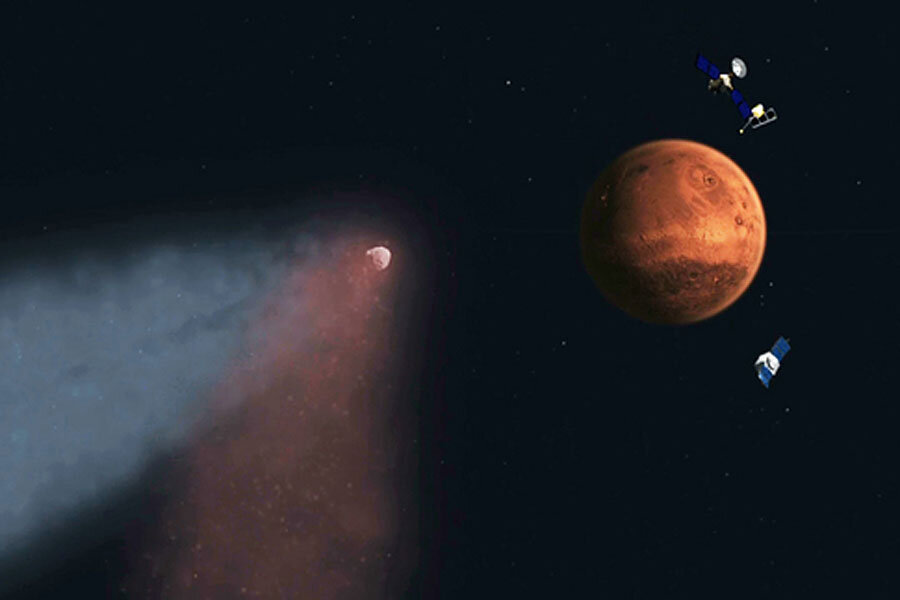

A rare close encounter between Mars and a comet last month pummeled the Red Planet with cometary dust, which likely left a yellow glow in the Martian sky, scientists revealed today (Nov. 7).

Scientists studying the Oct. 19 Mars flyby of Comet Siding Spring said they were shocked at the amount of dust the comet showered down on the Red Planet. While it's too early to say exactly how much dust the comet actually dumped, early estimates peg it at about a few thousand kilograms, according to Nick Scheider, a lead scientist for a dust-measuring instrument used in the study.

"We ended up with a lot more dust than we ever anticipated," said Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division. "It surprised us." [Photos of Comet Siding Spring at Mars]

Green said models of the flyby underestimated the size of the comet's dust tail and overestimated how much it would spread out before reaching Mars. NASA positioned its satellites behind Mars to protect them from the dust. In October, NASA scientist Michelle Thaller told Space.com that the dust particles could be traveling at speeds reaching 100,000 mph (27,777 km/h).

"Observing how comet dust slammed into the upper atmosphere makes me very happy we decided to put our spacecraft on the other side of Mars at the peak of the dust tail passage," Green said today. "I believe hiding them like that really saved them."

The scientists using the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, an instrument aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, announced a refined value for the size of the comet's nucleus — the solid, central portion made of rock and ice — of 1.2 miles (2 km), which is smaller than expected.

The falling dust particles, just like meteors in Earth's atmosphere, burn up as they go down, so the shower would have created a brilliant light show for anyone standing on Mars at the time. Different elements can create different colors when they burn, and Schneider said it is likely the sky would have had a distinctly yellow glow, due to high levels of sodium.

Schneider is instrument lead for the Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph, aboard the MAVEN spacecraft,which is the newest NASA satellite to arrive at Mars. The instrument also detected iron, zinc, potassium, manganese, nickel and chromium. The most noticeable difference in the composition of the dust, compared with the Martian atmosphere, was an overwhelming presence of magnesium.

"We all were sort of pressed back in our chairs seeing this booming [magnesium] signal," Schneider said. Magnesium in particular, along with iron are "not what you expect for atmospheric ingredients but they are what you expect from comet dust."

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Shallow Subsurface Radar (SHARAD) spacecraft showed the effects of the dust on the Martian atmosphere. The SHARAD maps the Martian surface by sending radar blips from its orbit down to the ground. The image above shows the surface created by SHARAD, both before (top) and after (bottom) the dust shower. The dust clearly obscured the signals, making its surface image significantly blurrier.

The plus side of the overwhelming dust shower is that now NASA scientists have a trove of data to sift through, which will hopefully answer questions about the comet and its origins. Comet Siding Spring is from a region called the Oort Cloud, a massive ring of icy bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Green said scientists believe this is comet Siding Spring's first trip to the inner solar system. The farthest point of its orbit may be 50,000 times the distance from the Earth to the sun, or about 1 light year. Siding Spring is also a remnant of the earliest days of the solar system, and living in such an icy environment may have helped preserve it. If scientists can analyze the comet, they may unlock new secrets from those early days of our local cosmic home.

"Never before have we had the opportunity to observe an Oort Cloud comet up close," Green said. While he says four to five Oort Cloud comets enter the inner solar system each year, they move too fast for a satellite to catch up to. Siding Spring was a special case. "Instead of going to the comet, it came to us."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article onSpace.com.

- Comet's Close Encounter with Mars Explained (Infographic)

- Comet Quiz: Test Your Cosmic Knowledge

- Best Close Encounters of the Comet Kind

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.