Scientists discover origins of moon's largest basin

Loading...

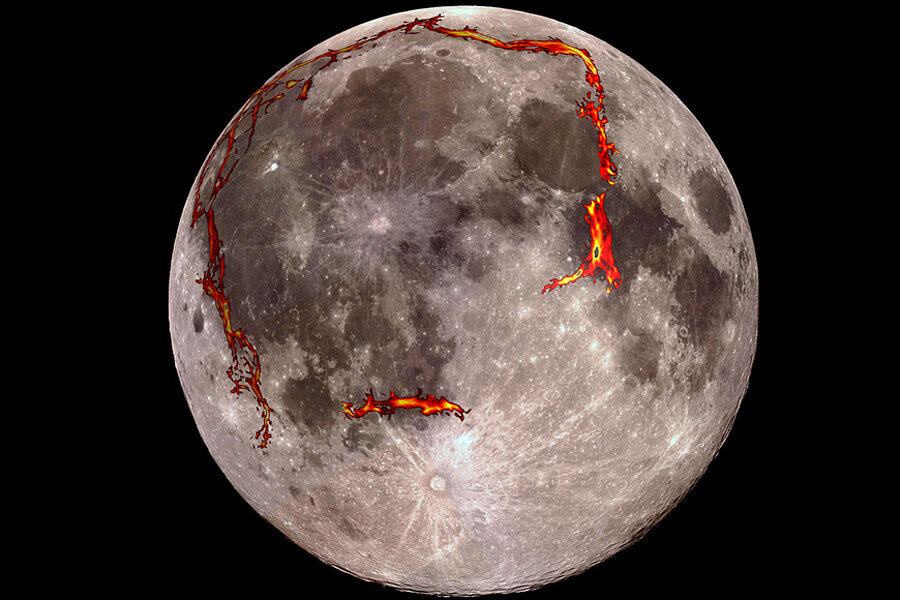

A massive feature on the moon formed due to lunar rifts, in a surprise revision to earlier theories, research shows. Previously, scientists thought the moon's Ocean of Storms was a round crater left after a giant impact, but now researchers have found it is underlain by a giant rectangle created by cooling lunar lava as the moon formed.

This finding reveals the early moon was far more dynamic than previously thought, scientists added.

The Ocean of Storms, or Oceanus Procellarum, is the largest of the moon's maria, giant dark spots visible on the near side of the moon. Early astronomers, mistaking these features for oceans, named them maria, Latin for seas. However, they are actually giant plains of the dark rock basalt. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Facts]

Stormy history for Ocean of Storms

Scientists had previously thought the Ocean of Storms was created by a giant cosmic impact that left a crater about 2,000 miles wide (3,200 kilometers) that filled with lava. Now, data from NASA's GRAIL missionreveals that Procellarum is not round, but instead is surrounded by a strange giant rectangle underneath the moon's surface. This suggests the Ocean of Storms was not caused by a meteor strike on the moon. Instead, researchers suggest, it formed as the moon's surface rifted apart.

"GRAIL has revealed features on the moon that no one anticipated before we had this data in hand," said lead study author Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna, a planetary scientist at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. "One can only wonder what might lie hidden beneath the surfaces of all of the other planets in the solar system." [NASA's GRAIL Moon Gravity Mission in Pictures]

NASA's twin GRAIL spacecraft, named Ebb and Flow, orbited the moon and measured how the strength of the moon's gravitational pull varied over its surface. Anything that has mass has a gravitational field that pulls objects toward it, and the strength of this field depends on the amount of mass in the object. Variations in the strength of the moon's gravitational pull can therefore help reveal how mass is concentrated there below the surface. NASA launched the GRAIL moon gravity probes (the name is short for Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) in September 2011. The mission ended in December 2012 when the two spacecraft were intentionally crashed into the moon's surface.

The ultra-precise gravity map of the moon from the GRAIL mission unexpectedly revealed a set of linear structures arranged in a rectangular shape about 1,600 miles (2,600 km) wide around Procellarum. The angular shape of the Ocean of Storm's borders reveal it was not created by a cosmic impact, which would have left a crater with a circular rim.

"The observed pattern of gravity anomalies on the moon is so strikingly geometric and in such an unexpected shape that it is forcing us to think in new and different ways about the processes operating on the moon and planets in general," Andrews-Hanna told Space.com.

Lunar lava and moon geometry

The researchers suggest these newfound structures are the remnants of valleys filled in with frozen lava. These valleys arose as the surface of the moon rifted open.

"As a solid cools and contracts, fractures and faults can form, and these fractures will commonly take on a polygonal pattern," Andrews-Hanna explained. "An excellent example of this is found in cooling lava flows on Earth where the lava breaks up into hexagonal columns, as can be seen at Devil's Postpile National Monument in California. These hexagons form because when three cracks intersect, they do so at 120-degree angles, and the only polygon on a flat surface that you can make with all 120-degree angles is a hexagon. These 120-degree intersections are seen at all scales, from the intersections of centimeter-scale cracks in drying mud to the intersections of giant rift valleys in eastern Africa."

On the moon, these ancient rift zones took on a rectangular order.

"Geometry on a sphere is different than geometry on a flat surface — this is why airplanes appear to follow curved paths when you look at their flight trajectories on a map," Andrews-Hanna said. "For a feature of the size of the Procellarum region, a polygon with 120-degree corner angles has four sides instead of six — or, stated another way, a square the size of Procellarum on the surface of a sphere the size of the moon has 120 degree angles instead of the 90 degree angles you expect on a flat surface."

The rift valleys filled in with lava until 3.5 billion years ago. This lava likely came from sources within the rift valleys themselves, Andrews-Hanna said. It remains uncertain whether the rift valleys formed before or during the volcanism that filled Procellarum with the lava that cooled to form the black rock that currently dominates the area, he added.

Rift zones are well known on Earth, Venus and Mars, but previously unknown on the moon. "This reveals a much more dynamic early moon than we had previously envisioned," Andrews-Hanna said. "I think we are only just beginning to understand the earliest history of the moon."

The newfound pattern of structures on the moon is quite similar to the structures seen on Saturn's icy moon Enceladus, which may have experienced a similar geological history, the researchers noted. Prior research had not predicted these structures on either the moon or Enceladus, "which tells us that we have much left to learn in order to understand the full spectrum of planetary evolution," Andrews-Hanna said.

The research is detailed in the Oct. 2 edition of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- How the Moon Formed: 5 Wild Lunar Theories

- 10 Coolest Moon Discoveries

- Moon Master: An Easy Quiz for Lunatics

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.