What happened on Mars? NASA's MAVEN arrives Sunday to find out.

Loading...

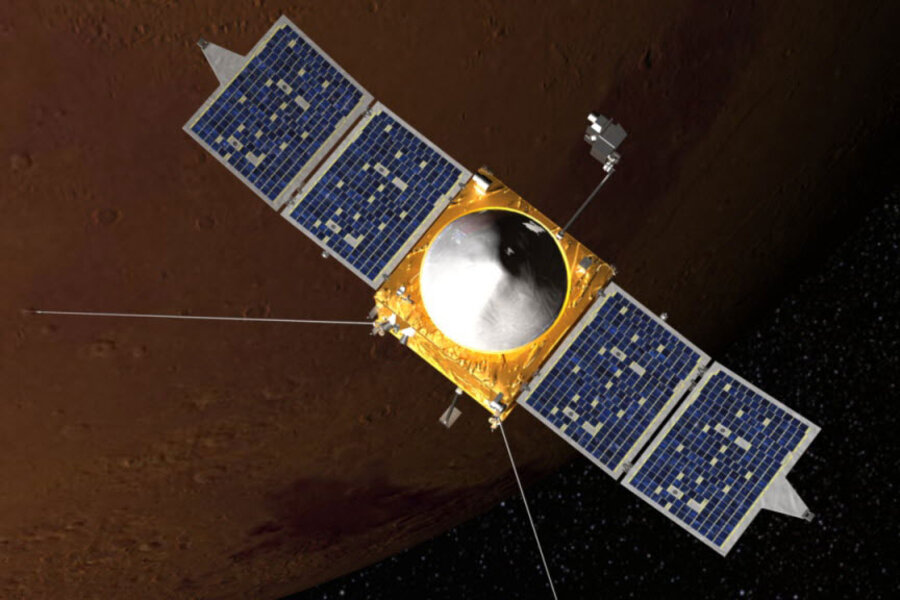

NASA's latest Mars orbiter MAVEN is on final approach to the red planet, leaving mission scientists and flight controllers with little more to do than make sure their seats are in the full, upright position with tray tables securely locked.

The craft is slated to begin orbiting Mars Sunday night at 9:37 Eastern Daylight Time – a maneuver that will be fully automated, given the 12.5 minutes it would take radio commands from Earth to reach the craft.

The orbiter, which launched last November, is slated to spend one Earth year gathering detailed information about Mars's upper atmosphere and how that atmosphere interacts with the stream of charged particles coming from the sun in what's known as the solar wind.

"MAVEN is about looking at the history of the atmosphere" in order to understand the history of a planetary environment that once was hospitable for microbial life on its surface but since has became downright hostile to it, said Bruce Jakosky, an astrobiologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder and the $671 million mission's lead scientist, during a final-approach briefing Wednesday.

Over the past decade rovers and landers have shown that the planet once hosted liquid water on its surface, forming lakes, rivers, and streams. The planet's atmosphere would have been much warmer and far more dense than it is today in order for liquid water to remain stable on the surface. Today, the planet is a frigid desert whose atmosphere has a density only about 1 percent that of Earth.

Any global magnetic field the planet had early in its history has little left to show for it, leaving the atmosphere increasingly vulnerable to being stripped away and carried into space by the solar wind – or so the reigning theory goes. MAVEN is designed to test that idea.

Nature is coming to MAVEN's aid in unlocking the secrets of Mars' upper atmosphere. On Oct. 19, comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring will flit past Mars, coming within about 81,000 miles of the planet's surface. MAVEN, along with the European Space Agency's Mars Express and other assets at the red planet, will observe the event.

The odds of such a close approach at Mars are about one event in a million years, so on one level, the comet is a bonus. But it's also risky. The team will be taking steps to minimize the risk that MAVEN could get smacked by comet dust by ensuring that Mars is between MAVEN and the comet during the period of heaviest dust bombardment, notes David Brain, another member of the MAVEN science team at the University of Colorado. Still MAVEN will be able to take some important observations of the comet itself, as well as measurements of the comet's influence on the upper atmosphere.

For instance, if the comet sheds significant amounts of dust, that dust would be expected to heat the upper atmosphere, causing it to expand, Dr. Jakosky said. Water from the comet would be expected to work its way into the upper atmosphere, heralded by an increase in the abundance of hydrogen.

By looking at the upper atmosphere before and after the comet's passage, and by seeing how long it takes for any changes to decay, the team will learn a great deal about the physical processes operating in the upper atmosphere today, Jakosky explained.

In addition, as the comet approaches, MAVEN's mapping ultraviolet spectrometer will observe the comet's halo, or coma, to map the distribution of chemical elements inside it.

"With the ability to image the whole comet as it's getting closer, we should have some pretty spectacular results," he said.

MAVEN currently is hurtling toward Mars at about 10,500 miles an hour and needs to shed about 2,600 miles an hour of that speed to allow Mars' gravity to capture it. To ease the pace of those odometer ticks, MAVEN will orient itself so that its six main engines can slow the craft sufficiently during a 33-minute orbital-insertion burn.

That will put MAVEN into an initial 35-hour orbit that will carry it 27,700 miles from Mars before it swings back to within 236 miles of the surface.

During MAVEN's first six weeks at Mars, mission controllers will tighten that orbit until the craft swings around the planet every 4.5 hours – bringing it to within 93 miles at its closest approach, then back out to about 3,900 miles before returning, said Guy Beutelschies, the mission's program manager at Lockheed-Martin Space Systems Company, in Littleton, Colo.

During the six weeks of tweaking orbits, which includes the Siding Spring observations, researchers will be checking out the craft's suite of eight instruments.

If all goes well and there's money in NASA's budget, MAVEN could operate for a full Martian year, allowing it to make its measurements across seasons for a more detailed look at the processes in the upper atmosphere that could have cost Mars its "habitable" status.