Cosmic 'magnifying glass' helps scientists see something really, really, really far away

Loading...

In a surprising discovery, astronomers have found a faraway galaxy that doubles as a cosmic "magnifying glass." At 9.6 billion light-years away, it could be the most distant such object known to science, NASA announced today (July 31).

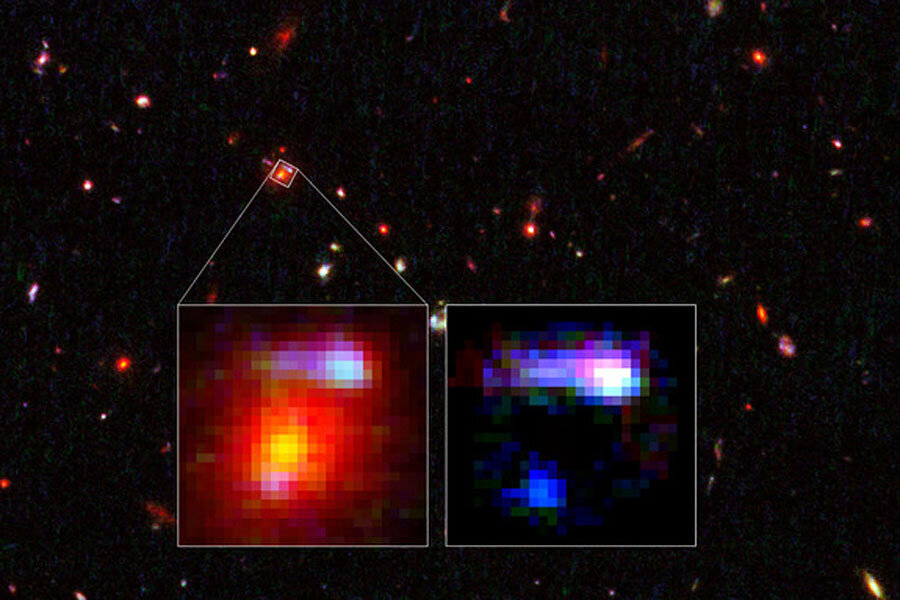

Spotted in observations from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and the Hubble Space Telescope, the galaxy is big enough to magnify an even more distant galaxy 10.7 billion light-years away, thanks to a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Through lensing, the gravitational field of a massive foreground object bends, warps and magnifies the light from more distant objects. This phenomenon can reveal extremely dim, faraway galaxies that astronomers otherwise wouldn't be able to see. [The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

But finding a galaxy huge enough to act as a lens is rare. Most of the hundreds of lensing galaxies astronomers know about today are relatively nearby. When peeking into the early universe, astronomers don't expect to find a lensing galaxy neatly stacked in front of another, smaller galaxy in the background, lead researcher Kim-Vy Tran of Texas A&M University in College Station said in a NASA statement.

Tran used the analogy of looking through an actual magnifying glass to explain: "Imagine holding a magnifying glass close to you and then moving it much farther away. When you look through a magnifying glass held at arm's length, the chances that you will see an enlarged object are high. But if you move the magnifying glass across the room, your chances of seeing the magnifying glass nearly perfectly aligned with another object beyond it diminishes."

The newfound magnifying galaxy belongs a distant galaxy cluster known as IRC 0218. It is 180 billion times more massive than our sun, and at 9.6 light-years away, it breaks the previous record-holder for most distant lensing galaxy by 200 million years, according to NASA.

Tran and colleagues discovered the galaxy while studying star formation in IRC 0218 using spectrographic data from the Keck Observatory. She saw a strong spot of hot hydrogen gas — a signature of star formation — that seemed to be emanating from a giant old elliptical galaxy. Tran was worried that she made a mistake with her observations because previous research showed that this elliptical galaxy had long quit making stars.

But after analyzing other images taken by the Hubble telescope, Tran realized she hadn't made a mistake, but was looking at a smaller, more distant spiral galaxy undergoing a burst of star formation behind the galaxy in IRC 0218. In the Hubble images, the distorted light from the galaxy 10.7 billion light-years away appeared as smears that were bluish in color (as galaxies with young stars often do).

The findings were published in The Astrophysical Letters Journal on July 10. A version of the paper is free to read online at the preprint service arxiv.org.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

- Images: Peering Back to the Big Bang & Early Universe

- How the Hubble Space Telescope Works (Infographic)

- Most Amazing Hubble Space Telescope Discoveries

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.