Is this deep-sea octopus the world's greatest mom?

Loading...

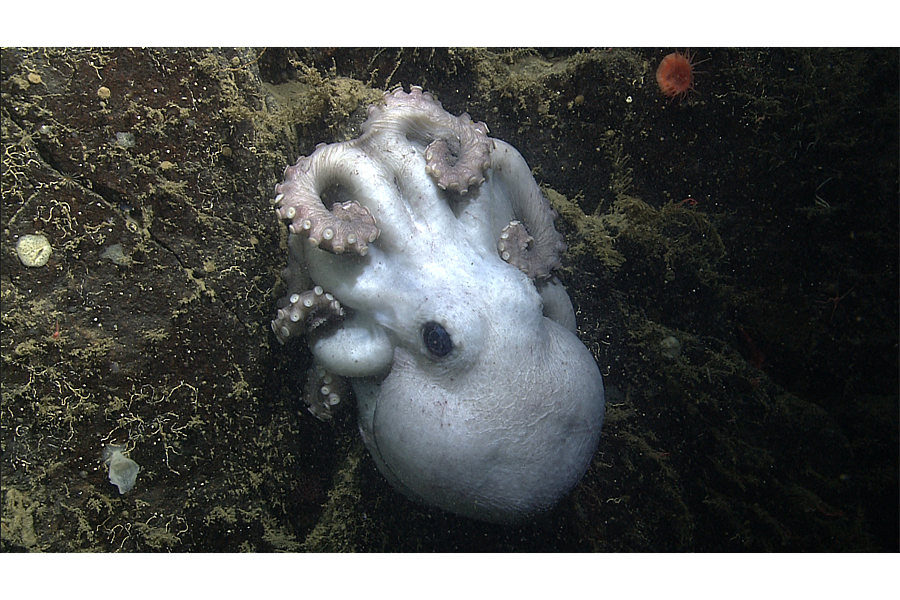

Off the coast of central California, there lived an eight-armed mom who displayed extraordinary devotion to her children.

More than 4,000 feet below the surface of the ocean, an octopus of the genus Graneledone boreopacifica used her own body as a shield for her young for a record-breaking four and half years.

Never leaving even for a snack, she used her eight tentacles to protect and care for some 160 eggs.

After spending 53 months of her short life clinging to this rock, the mother octopus likely died. But she had already provided her babies with necessary oxygen and protection in the frigid depths.

This would be her only brood, but they would have matured to near adulthood while under her care.

This octopus is the subject of a paper published this week by researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) in the journal PLOS ONE. After noticing the mother on her rocky perch for the first time in May 2007, surveying researchers vowed to return.

Scientists have often explored the Monterey Canyon, a deep-water chasm off the central California coast, using remote deep-sea vehicles. The researchers first spotted their brooding subject after noting that the same location had been empty a month before.

The researchers returned 18 times before this octopus family disappeared, leaving behind only eggshells. "It got to be like a sports team we were rooting for," Bruce Robison, study author, told BBC News. "We wanted her to survive and to succeed."

"Each time we went down it was more of a surprise," Dr. Robison said. "We found her there again and again and again, past the point that anybody expected she'd persist."

Never before had researchers seen a brooding period last this long. The previous record-holder was a giant red shrimp, who cared for eggs for 20 months.

What was especially surprising was that the octopus did not eat the whole time. The researchers watched through a remote video feed on the deep-sea research vehicle as the octopus pushed away small crabs and shrimp that passed by. Her only intent, it seemed, was to protect her eggs.

As they develop, the eggs require lots of oxygen. So this caring mother continuously spread oxygenated seawater over her eggs.

She also protected her babies from being covered in silt, sand or other underwater debris, and from being eaten by predators.

Her dedication seems to have paid off. This type of octopus, along with other other deep-sea creatures, have previously been found to emerge more mature than shallow water animals. Although still small, these babies are able to survive on their own.

A shallow-dwelling mother octopus typically cares for her brood for just one to three months, but those babies hatch less mature. In the challenging environment of deep-sea living, the longer brooding period may provide a higher chance of survival for the eight-armed babies.

"These surprising results emphasize the importance of parental care in producing well-developed offspring that can cope with the rigors of the deep-sea habitat," Robison said in a news release. "Because the brooding period is temperature dependent, the results also provide a caution about the potential consequences of our changing climate."