How common are black holes? Distant galaxy reveals intriguing clues.

Loading...

Scientists have just discovered a distant galaxy with not one but three supermassive black holes at its core.

The new finding suggests that tight-knit groups of these giant black holes are far more common than previously thought, and it potentially reveals a new way to easily detect them, researchers say. Supermassive black holes millions to billions of times the mass of the sun are thought to lurk at the hearts of virtually every large galaxy in the universe.

Most galaxies have just one supermassive black hole at their center. However, galaxies evolve through merging, and merged galaxies can sometimes possess multiple supermassive black holes. [See amazing photos of galaxy mergers]

Astronomers observed a galaxy with the alphabet soup name of SDSS J150243.09+111557.3, which they suspected might have a pair of supermassive black holes. It lies about 4.2 billion light-years away from Earth, about "one-third of the way across the universe," said lead study author Roger Deane, a radio astronomer at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

To investigate this galaxy, the scientists combined the signals from large radio antennas separated by up to 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers), a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI). Using the European VLBI Network, the researchers could see details 50 times finer than is possible with the Hubble Space Telescope.

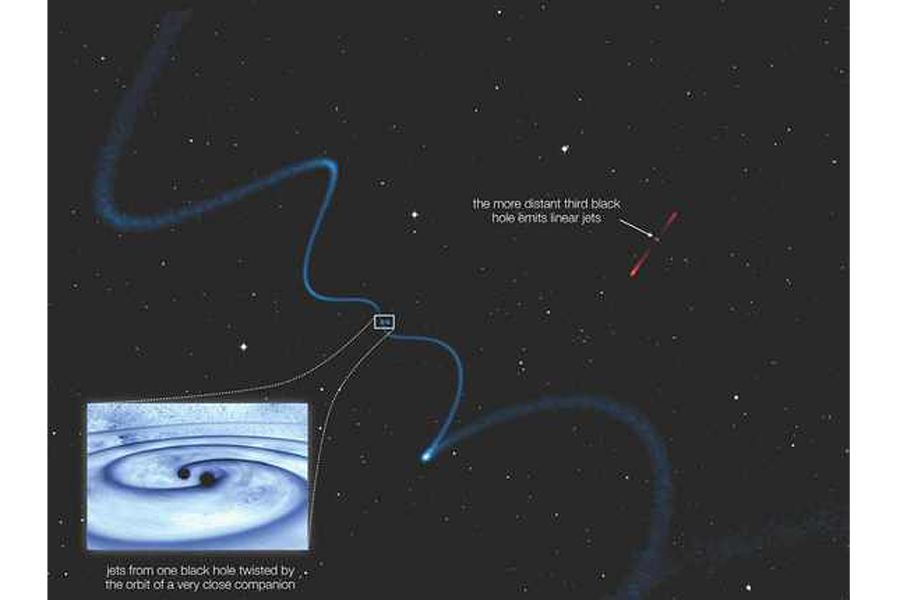

The astronomers unexpectedly discovered that the galaxy was actually not home to two supermassive black holes, but three. Two of the black holes in this trio are very close together, which previously made them look like one black hole.

"All three of the black holes have masses around 100 million times that of the sun," Deane told Space.com.

Scientists had previously known of four triple black-hole systems. However, the closest pairs of black holes in those triplets are about 7,825 light-years apart. In this newfound trio of supermassive black holes, the closest pair of black holes is only about 455 light-years apart, "a very close pair of black holes," Deane said — the second-closest pair of supermassive black holes known.

The researchers found this "tight pair" of black holes after searching only six candidate galaxies. This suggests that tight pairs of supermassive black holes "are far more common than previous observations have found," Deane said.

Knowing how often supermassive black holes merge is key to discovering how they might influence their galaxies, the researchers noted. Supermassive black holes can shape the evolution of their galaxies with blasts of energy given off by turbulent matter, which gets sucked toward the black holes.

Although tight pairs of supermassive black holes might previously have been difficult to tell apart, the researchers discovered that the pair they saw left a helical or corkscrew-like pattern in the large jets of radio waves they emitted. This suggests that twisted jets may serve as easy-to-find signals of tight pairs without the need for extremely high-resolution telescopic observations, such as those from the European VLBI Network.

"The twisted radio jets associated with close pairs may be a very efficient way to find more of these systems that are even closer together," Deane said.

Closely orbiting black holes are expected to generate ripples in the fabric of space and time known asgravitational waves, which are theoretically detectable even from across the universe. By finding more tight pairs of black holes, scientists can better estimate how much gravitational radiation these pairs generate, Deane said.

"The end goal is a self-consistent understanding of how two separate black holes that start out in two interacting galaxies slowly get drawn closer to one other, impact their host galaxies, emit gravitational waves and eventually merge to become one, in what is predicted to be a violent event," Deane said.

The scientists detailed their findings in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

- The Search for Gravitational Waves (Gallery)

- Black Holes: Warping Time & Space | Video

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.