Ancient Egyptians used wet sand to drag massive pyramid stones, say scientists

Loading...

For years researchers have been trying to unravel the mystery behind the ancient Egyptian pyramids.

Apart from the great architecture, one question that long puzzled scientists is how Egyptians managed to move those colossal pyramid stones – some of which weigh several tons.

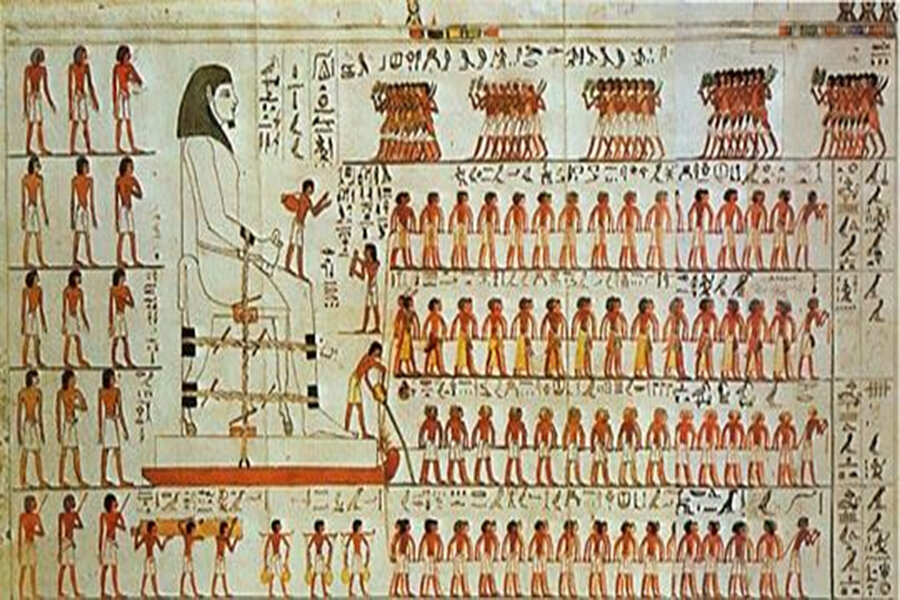

Researchers now suggest that the stones were dragged over wet sand. Their study, published in the journal Physical Review Letters and titled "Sliding Friction on Wet and Dry Sand", is based on a wall painting from the tomb of Djehutihotep, which depicts a person standing in front of a wooden sledge and wetting the sand.

Daniel Bonn, a professor of physics at The University of Amsterdam and a lead author of the paper, says that after he came across the painting, he carried out a laboratory experiment where he and his team build a smaller version of "the Egyptian sledge in a tray of sand" with weights ranging between 100 grams to a few kilograms.

"When the sand was dry, a heap of sand formed in front of the sled, hindering its movement; a relatively high force was needed for the sled to reach a steady state. Adding water made the sand more rigid, and the heaps decreased in size until no heap formed in front of the moving sled and therefore a lower applied force was needed to reach a steady state," researchers note in their synopsis.

But the trick is to use the optimum amount of water. If the sand is too dry or too wet, it would hinder the movement of the sledge, Dr. Bonn told the Monitor.

Everyone knows that dry sand doesn't make good sandcastles. But adding water does the trick. "Once there is enough water, these bridges act like glue, keeping the grains in place. This is great for sand castle building, and also, it turns out, for sand transportation," researchers noted.

Less force on wet sand also means that the number of men needed to pull the stones could be reduced by as much as half, Bonn says. The Egyptians probably knew of this "handy trick."

Wetting sand has for long been associated with some kind of ritual. This study aims to debunk this view, Bonn adds.

Bonn says based on the kind of jar that the man is seen using in the wall painting, it was water and not oil or any other lubricant.

But other researchers say that Egyptians also used desert clay as a lubricant. Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) says that thin tafla clay layers have been seen under multi-ton blocks either left in place at the wall of a temple or other monument, or where workers left the blocks en-route, and not yet in their intended place in a building.

"I have also seen blocks left in such 'frozen moments' on sand, so maybe the wet sand hypothesis works," he wrote in an email. "I would need to see it myself. On the pyramid casings, the builders used millimeters-thin layers of whitish-pink gypsum mortar – finer even than Tafla, to make the final slide and adjustment into fits with an adjacent block so fine, you cannot get a knife or even a razor blade in between."

Dr. Lehner has seen it for himself when he was involved with the WGBH NOVA program during which he and his team built "a hauling track of wood beams, sand and limestone debris, and then coated it with a thin layer calcareous desert clay, called tafla in Arabic. We had workers pull a two-ton limestone block on a wooden sledge, while one worker wetted the clay by sprinkling or pouring water in front of the runners of the sledge (he was crouched and moving backward as the sledge progressed). The slick clay acted as a lubricant and greatly facilitated pulling the block."

While the wet sand hypothesis is possible, Lehner says that it could be that sand was not the only thing they used. Sand could have been used for longer, coarser movements. Tafla, being fine, would have been used for shorter, more precise movements and adjustments whereas gypsum mortar, possibly even finer than talfa, would have been used for the most precise adjustments – setting the outer casing stones, he added.