Scientists spot a new Earth-sized planet that might have liquid water

Loading...

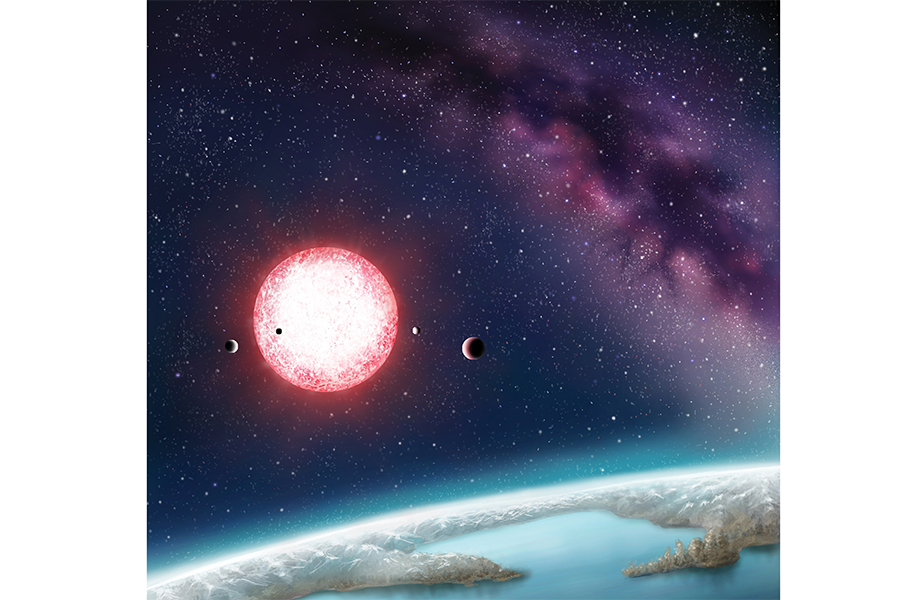

An international team of researchers have now discovered a new rocky planet that just might have liquid water on its surface.

The planet, spotted using NASA's Kepler telescope and dubbed Kepler-186f, is the fifth and outermost planet in a system found orbiting the M dwarf star Kepler-186, which is located about 500 light years from Earth, in the Cygnus constellation.

Researchers determined the radius of the planet through the "transit" method, which analyzes the periodic dimming in the brightness of a star as the planet passes in front of it.

Using this information, scientists calculated that Kepler-186f is 10 percent larger than our planet. The planet is one of five in a solar system. The other four all measure less than 1.5 times the size of Earth..

"What we've learned, just over the past few years, is that there is a definite transition which occurs around about 1.5 Earth radii," said San Francisco State University astronomer Stephen Kane, a co-author on the paper, in a press release. "Between 1.5 and 2 Earth radii, the planet becomes massive enough that it starts to accumulate a very thick hydrogen and helium atmosphere, so it starts to resemble the gas giants of our solar system rather than anything else that we see as terrestrial," he said

At only 1.1 Earth radii, it is highly unlikely that Kepler-186f has a hydrogen-helium dominated atmosphere, says Dr. Kane, "so there's a very excellent chance that it does have a rocky surface like the Earth." In a broad survey completed a few months ago, scientists found that the smaller the radius, the more likely a planet is to be rocky – a terrestrial planet instead of a gas planet,.

Situated at the outer edge of the so-called "habitable zone" of its star, the planet might be a little too cold, creating a possibility for its water to freeze. "It is also slightly larger than the Earth," Kane notes, "so the hope would be that this would result in a thicker atmosphere that would provide extra insulation," making the surface warm enough to keep water in a liquid state and encourage geological activity, Kane said.

Of course, location alone does not mean that Kepler-186f is like our Earth. "Being in the habitable zone does not mean we know this planet is habitable. The temperature on the planet is strongly dependent on what kind of atmosphere the planet has," said Thomas Barclay, research scientist at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute at Ames, and co-author of the paper. "Kepler-186f can be thought of as an Earth-cousin rather than an Earth-twin."

There are significant differences between the two systems.

"We're always trying to look for Earth analogs, and that is an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone around a star very much the same as our Sun," said Kane, who is the chair of Kepler's Habitable Zone Working Group. "This situation is a little bit different, because the star is quite different from our sun."

The star Kepler-186 is much cooler and smaller – half the size and mass of our sun – meaning that its star system has a much smaller habitable zone. So, despite the planet taking 130 days to go around its star (almost one-third of the time the Earth takes to go around the sun), it could still receive enough light from its star for there to be liquid water on its surface. The other four planets within the system – Kepler-186b, Kepler-186c, Kepler-186d, and Kepler-186e – go around their sun every four, seven, 13, and 22 days, respectively, making them too hot for life.

It is too soon to know whether Kepler-186's stellar activity – flares, ejections of plasma, and so on – will affect the planet's potential habitability, say researchers.

"We don't know exact age of the star," Elisa Quintana of the SETI Institute at Nasa Ames Research Centre in Moffett Field, California, and lead author of the study told the Monitor. But based on its slow rotation and its relative quiescence – the team detected only one flare in four years – the star is likely to be several billion years old. "Beyond that, we don't know."

Yet even if the star were more active, its outbursts might not matter for any potential life on the planet. Kepler-186 is at the larger end of the scale for M-dwarfs, so it is relatively bright. That puts its habitable zone far enough away that even an active Kepler-186 wouldn't inflict "all of the typical complications you hear about for M dwarfs," she says. The planet also "is far enough away that we don't know if it's tidally locked – it could be or it couldn't be," she says.

As of now, researchers do not know the planet's mass. But Kane said an estimate of this can be made based on previous discoveries of other planets with similar radii. Using mass and radius, scientists can then calculate the average density of the planet, "and once you know the average density of a planet, then you can start to say whether it's rocky or not," Kane said. Based on their models, the team argues that the planet we are seeing is terrestrial – rocky like our own.

"The diversity of these exoplanets is one of the most exciting things about the field," he added. "We're trying to understand how common our solar system is, and the more diversity we see, the more it helps us to understand what the answer to that question really is."

The findings of the study are published in a paper titled "An Earth-sized Planet in the Habitable Zone of a Cool Star" in the April 18 issue of Science.

Monitor staff writer Pete Spotts contributed to this report.