Alien-seeking space observatory to hover between Earth and sun

Loading...

The search for alien worlds has received an unprecedented burst of energy, with the European Space Agency's (ESA) vote this week to fund a 34-telescope observatory that will scan the sky for habitable planets, from a fixed spot between Earth and the sun.

The new PLATO mission (Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars) projects a 2024 launch of the observatory, which will seek out the Earth-like planets believed to orbit neighboring stars, as part of ESA's Cosmic Vision program.

“PLATO will begin a completely new chapter in the exploration of extrasolar planets” said Heike Rauer, an astrophysicist with the German Aerospace Center, who leads the PLATO mission. “We will find planets that orbit their star in the life-sustaining ‘habitable’ zone: planets where liquid water is expected, and where life as we know it can be maintained.”

In the past 20 years, search missions run by both ESA and NASA have located over 1,000 exoplanets orbiting alien suns. But of those, very few dwell at habitable distances from their suns, and those that do are unlivable for other reasons. None of the identified exoplanets has yet yielded precise determinations of its mass, radius, or age.

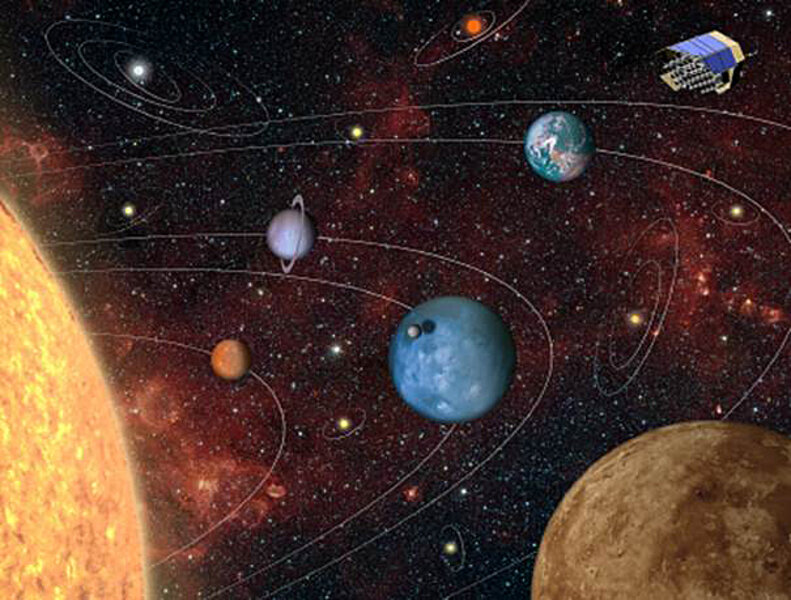

PLATO's focus on life-likely planets sets it apart from existing planet-seeking missions, as does its destination: a so-called Lagrangian point between the Earth and the sun, where the two bodies' competing gravitational pulls will hold the satellite in place.

Unlike points on Earth, or in the orbital paths of other satellites, this stable location will allow the observatory to scan its interstellar quarry continuously, without Earth itself blocking half the sky, the blinding interruption of terrestrial daylight, or the blurring caused by Earth's atmosphere.

Using 34 telescopes rather than a single lens, the PLATO mission will transport the largest Earthly camera system ever to be launched into space, whose sensors will have a combined surface area of almost ten square feet.

"The individual telescopes can be combined in many different modes and bundled together, leading to unprecedented capabilities to simultaneously observe both bright and dim objects," explained a press release from England's University of Warwick, whose physicist, Don Pollacco, leads PLATO's science consortium.

The telescopes will look for flickers in starlight that indicate the passage of an orbiting planet. Having pinpointed a planet, they will then measure its radius and mass, measurements which are necessary to distinguish between a gassy, low-density, uninhabitable planet like Neptune, and a rocky, iron-hearted orb like Earth.

Hundreds of researchers from across Europe and the world are working together on the PLATO mission, which plans to examine one million stars across half the sky.

PLATO is one of three Cosmic Vision projects now underway. The Solar Orbiter mission, which will conduct close-up observations of the sun, is planned for launch in 2017. And Euclid, an exploration of dark energy and dark matter, is planned for a 2020 launch. Each of these missions out-competed PLATO in prior applications for Cosmic Vision funding.

While Earth await's PLATO's launch, the search for exoplanets continues. NASA's TESS mission and ESA's ChEOPS mission, both scheduled for 2017 launches, will scan the sky as they orbit Earth. NASA's Kepler space observatory, which has been trailing Earth's path around the sun for the same purpose since 2009, remains aloft but can no longer point itself toward specific stars ever since the second of its four stabilizing wheels failed in May 2013.

While the prospect of meeting unrelated life forms has never stopped fascinating humans, the search for Earth-like planets promises other thrills as well.

“The observation of planets in many different states of their evolution will give us clues for the past and the future of our own planetary system," said Dr. Rauer. “By no means do we know all about the youth of our Solar System.”