Why some physicists aren't buying Hawking's new black hole theory

Loading...

Famed astrophysicist Stephen Hawking has shaken up the popular science world with his newest study about the basic nature of black holes, but is his idea revolutionary? Some scientists aren't convinced.

Hawking's new black hole study — entitled "Information Preservation and Weather Forecasting for Black Holes" — was published Jan. 22 through the preprint journal arXiv.org and has not yet undergone the peer review vetting process typical for academic papers. It attempts to solve a paradox surrounding the basic building blocks of how the universe works.

"Hawking's paper is short and does not have a lot of detail, so it is not clear what his precise picture is, or what the justification is," Joseph Polchinski of the Kavli Institute wrote in an email to SPACE.com. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

Current theories about black holes hinge upon what's known as the "firewall paradox." This paradox pits Einstein's theory of general relativity against quantum theory in the context of a black hole. The paradox, developed by Polchinski and colleagues about two years ago, is based upon a thought experiment about would happen to a person if he or she fell into a black hole.

If an astronaut fell into a black hole, according to Einstein's theory, he or she would simply float past a point known as the "event horizon" with "no drama." The event horizon refers to the point of no return at which not even light can escape from the black hole. The astronaut wouldn't realize he or she had drifted into the black hole at all. The black hole would then pull the astronaut apart before it crushed the space explorer into its dense core.

On the other side of the paradox lies quantum mechanics, the physics theory that explains the behavior of small particles. In the thought experiment, quantum theory suggests that an astronaut would not find a "no drama" area at the event horizon, but instead would encounter a "firewall" just inside the black hole that would destroy the unlucky traveler.

In 1974, Stephen Hawking found that matter and energy can escape a black hole through what is now known as Hawking radiation. However, he contended that the radiation would be so scrambled that scientists could never work backwards to understand what fell into the black hole in the first place. This violates a basic piece of quantum theory, the idea that information cannot be destroyed.

In 2004, Hawking had a change of heart and admitted he was wrong about information loss. However, no one is quite sure how information could escape a black hole. Information radiating out of a black hole is not compatible with general relativity, and destroying information isn't possible within the confines of quantum theory. So, who is right?

Hawking's two-page study attempts to resolve the issue by doing away with event horizons and replacing them with the idea of "apparent horizons."

"The absence of event horizons means that there are no black holes — in the sense of regimes from which light can't escape to infinity," Hawking wrote. "There are, however, apparent horizons, which persist for a period of time."

These apparent horizons shift with the behavior of quantum particles within the black hole. This theory suggests, then, that information can radiate from the black hole.

However, this idea doesn't seem to address the firewall paradox at all, said Raphael Bousso, a theoretical physicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

"It's not possible to have both of those things, to have no drama at the apparent horizon and to have the information come out," Bousso told SPACE.com. "Stephen just doesn't discuss this argument, so it's unclear how he means to address it."

Don Page, physicist at the University of Alberta in Canada, agreed. "I do not think that eliminating event horizons by itself solves the firewall problem, which is a subtle problem," he wrote in an email.

And an event horizon-free black hole isn't a new proposal, either, Page said.

"The idea that a black hole does not truly have an event horizon goes back more than a third of a century, and I would not be surprised if someone could trace it back even many years earlier," Page told SPACE.com via email.

A new PBS documentary about Hawking's life and work is set to air Wednesday (Jan. 29) night. Check local listings.

Read Hawking's full study, called "Information Preservation and Weather Forecasting for Black Holes," on arXiv.org: http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.5761

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

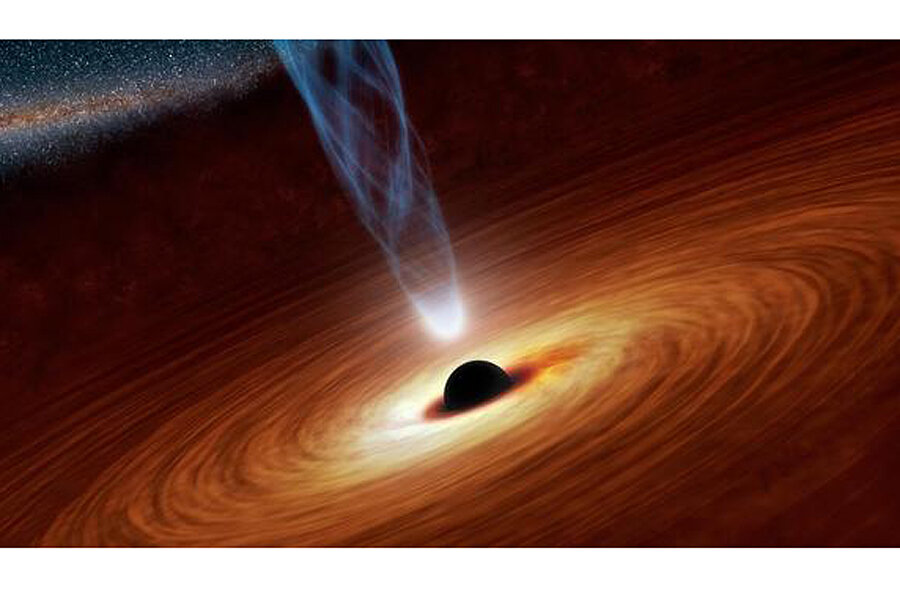

- Images: Black Holes of the Universe

- Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

- BLACK HOLES: Warping Space and Time

Copyright 2014 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.