Ants in space! Cygnus craft delivers 640 new astronauts to space station

Loading...

For millions of years, ants have been one of most industrious creatures on Earth. Now we're going to see how they fare in space.

With the help of NASA, a team of scientists now seeks to understand how the insects, renowned by biologists for their navigational and organizational skills, adjust to microgravity.

The experiment could provide us with a better understanding of foraging methods used by ants, the University of Colorado's Stefanie Countryman, one of the co-investigators of the experiment, told the Monitor.

After a two-day voyage, Orbital Science's robotic Cygnus spacecraft delivered the 640 small black common pavement ants to the International Space Station on January 12.

To avoid infestation, sterile worker ants were chosen for the project.

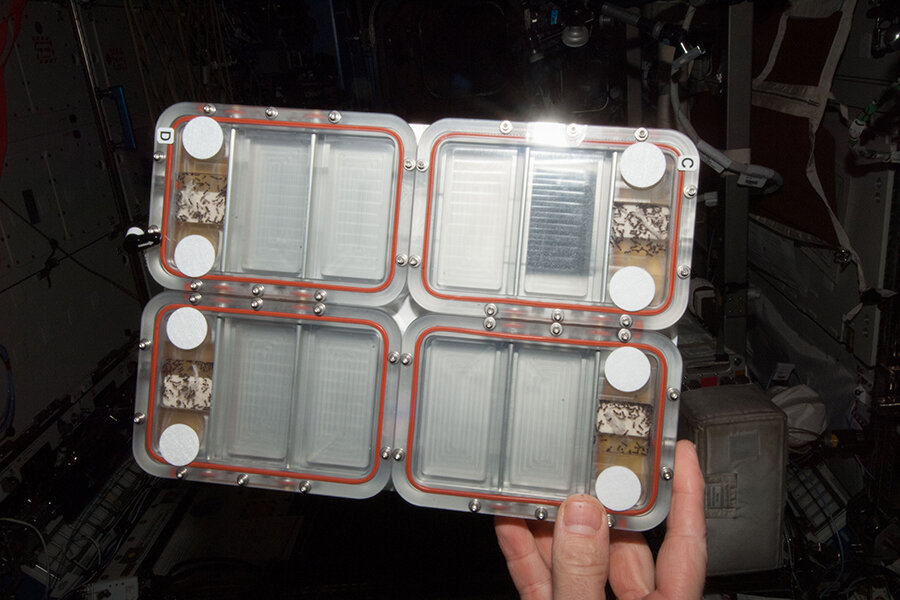

The ants were divided into eight equal groups – each consisting of 80 ants. They were assigned to their individual habitats, eight in total. A habitat, says Stanford biologist Deborah Gordon, principal investigator of the project, is a 4-inch by 6-inch covered arena made of acrylic with three sub sections – Nest, Forage Area 1, and Forage Area 2.

The ants were first kept in the nest area before the experiment was initiated. As soon as the ants reached the space station they were moved to Forage Area 1 – a more compact subsection within the habitat where density of ants was high. Their interactions and path shape were monitored on video for 25 minutes, according to NASA.

The moveable barrier between Forage 1 and 2 was removed. As a result, density of ants became less as they had more space to spread out, says Ms. Countryman. This interaction was recorded for another 30 minutes.

On Earth, ants adjust their search behavior depending on the size of the arena "by shifting from the small, circular search routine to straighter, broader paths, thus expanding the search network," said Dr. Gordon in a press release.

The researchers are now busy looking at the videos and studying the interactions between ants, says Countryman.

Scientists involved with the project chose ants because of their remarkable navigational skills. The ant doesn’t have a leader that can decide for the rest of the group. Instead, ants bump antennas into each other and are guided by smell, says Countryman.

In terms of density, scientists say that ants usually move in a circular pattern if they are in a high-density region. "Therefore ants kind of assume that there are a lot of us here, so it is ok to cover a smaller area," says Countryman. When the density decreases the ants seek to cover more ground therefore and move in straighter paths.

The results could provide insights into behavior of ants and may be useful in other systems that depend on "distributed algorithms," such as robots used in search-and-rescue operations.

"We have devised ways to organize the robots in a burning building, or how a cellphone network can respond to interference, but the ants have been evolving algorithms for doing this for 150 million years," Gordon said in the press release. "Learning about the ants' solutions might help us design network systems to solve similar problems."

This "Ants in Space" project is part of a K-12 educational curriculum and is partially sponsored by NASA, says Countryman. The program encourages students around the world to replicate such experiments carried out in space in their classrooms. The objective of the education program is to generate interest in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.