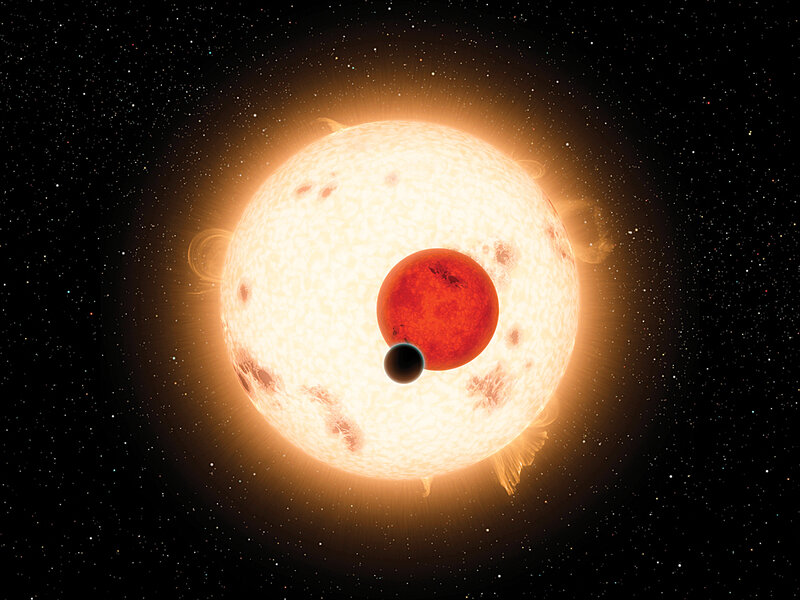

Remember Tatooine, the "Star Wars" planet with two suns? Astronomers found one such planet orbiting a binary star system 220 light-years from Earth. One star has about 69 percent of the sun's mass and is only about two-thirds the sun's size. The second sports only about 20 percent of the sun's mass and size. The partners take waltzlike spins around their joint center of mass every 41 days. The planet, Kepler-16b, is about the size of Saturn and orbits these cosmic dancers once every 229 days. Measurements yielding Kepler-16b's size and mass reveal that the planet is half rock and ice and half gas – hydrogen and helium. The planet orbits at the outer edge of the binary stars' habitable zone. While the planet itself may be inhospitable for life, some researchers theorize that the system could have produced a smaller rocky planet that could have become a moon to Kepler-16b.

A year later, scientists found Kepler-47b and c, two planets orbiting a close-binary star system 4,900 light-years away. The larger planet falls inside the habitable zone, orbiting once every 303 days. It's 4.6 times larger than Earth. So far, the planets' masses haven't been determined, although some researchers speculate that the larger planet could be a water world.